2012 was the warmest year on record according to NOAA, the nation's climate monitoring service. The Midwest was also in the grip of a severe drought. Those two factors have led to the lowest water levels in history for Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, which is considered one body of water hydrologically. The impact of the low lake levels on those who live on the Great Lakes is heavy.

2012 was the warmest year on record according to NOAA, the nation's climate monitoring service. The Midwest was also in the grip of a severe drought. Those two factors have led to the lowest water levels in history for Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, which is considered one body of water hydrologically. The impact of the low lake levels on those who live on the Great Lakes is heavy.

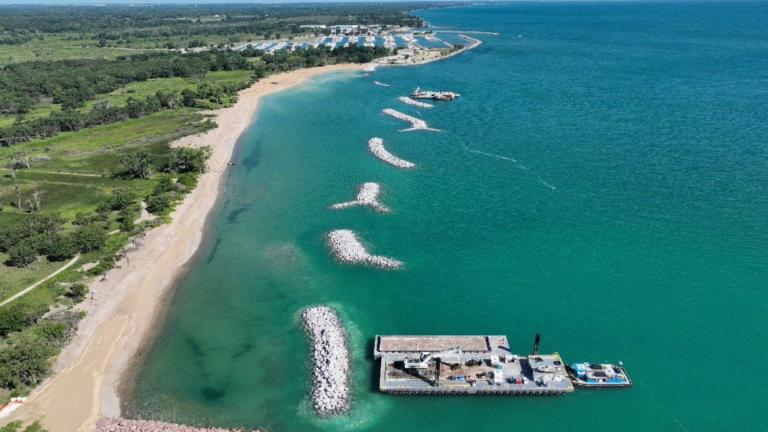

Leland Harbor is the heart of a northern Michigan town. The small town is quiet in the winter, but the population jumps ten-fold in the summer when tourists flock to the harbor, beaches and quaint shops. That tourist economy is now in jeopardy because of the dramatic drop in Lake Michigan's water level.

Harbor master Russel Dzuba said the lake is down more than two feet from its average, and that drop is threatening to close the harbor.

“The economic impact this harbor has on the community is strong. And when things are slow, the guy at the grocery store, the guy at the restaurant comes down and asks me what's going on. They want to know,” said Dzuba. “So, it’s an economic punch that we hate to think what happens if we cant keep that channel open.”

The guy asking the questions from the grocery store is likely to be Joe Burda. His family runs the only grocery store in town.

“The summer business in general keeps us open for the rest of the year. The boats and the traffic that the harbor brings in is a pretty big percentage of what we do in the summer,” said Burda.

The harbor is also a safe haven for boaters along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan.

“We feel morally obligated to keep this channel open,” Dzuba said. “There’s 75 miles stretch of Lake Michigan between Frankfurt and Charlevoix, and a very tempestuous, treacherous body of water out there, so we'll do everything we can to keep it open.”

The low water also endangers Leland's historic fishing industry: a huge tourist draw. Now the fishing boats, which were bought and are now run by the local preservation society, sit perilously close to the bottom of the lake. If the tugs do hit bottom, they will be stuck until water levels rise. That would be devastating to Fishtown and Leland, said Fishtown Preservation Society Executive Director Amanda Holmes.

“To have a tug and just have it sit there, is just to be an exhibit. To have a tug with incredible fisherman that are multigenerational bring all the knowledge to it, anyone who walks the docks and they see these boats come in, they're seeing something they don't get to see most other places in the entire Great Lakes,” said Holmes.

Across the peninsula from Leland, on Grand Traverse Bay, rocks and boulders, long under water, dot the now dry lake bed. Docks sit far from the water, and in nearby Suttons Bay, sand flats appear. Concrete blocks that once anchored boats now sit in just inches of water. If one were to walk down the beach in Suttons Bay in 1984, the water would have been almost a foot over one’s head.

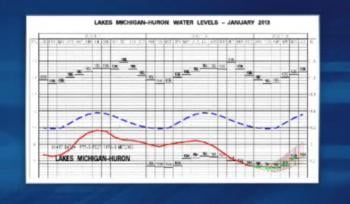

The Army Corps of Engineers confirms that Lake Michigan and Lake Huron water levels have hit an all-time low.

The Army Corps of Engineers confirms that Lake Michigan and Lake Huron water levels have hit an all-time low.

“In December, we hit a new historic low level in Lake Michigan and Huron. We have been monitoring lake levels since 1918. This is now the historic low level; it has not been this low before on Lakes Michigan and Huron,” said Roy Deda of the Army Corps.

Scientists at the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Ann Arbor, Mich. blame evaporation and less precipitation for the dropping lake levels.

“When the water temperatures increase, which they are right now, especially through the summertime; then, in the fall, when we have the cool air masses coming over the lakes, we have increased evaporation, and that evaporation rate has been exaggerated, particularly this year,” said Andrew Gronewold, hydrologist at GLERL. “We're also in a year where there’s been extremely low precipitation, so over the last year very little rain was coming in to the system, both in the form of snow melting in the springtime and then also direct rainfall onto the lakes themselves.”

Last winter was the fourth warmest winter on record. And those warmer temperatures lead to less ice formation and still more evaporation.

“When the lakes are changing that dramatically, that is a change in the climate,” Gronewold said. “Now what is causing the lakes to warm so much? That’s something that’s going to require some additional research.”

With Great Lakes water levels at historic lows, the only way to keep harbors open is by excavating or dredging the lake bottom. But Chuck May, who chairs the Great Lakes Small Harbors Coalition, said the money for dredging has dried up.

“You got almost a perfect storm hitting the Great Lakes harbors,” May said. “You've got low water and you've got lack of maintenance, lack of dredging, lack of infrastructure. You combine those two, and you've got situations where we truly face a crisis throughout the Great Lakes, harbor after harbor, and it’s just growing. And it's going to be much worse. And it's going to change, ultimately, the way of life and the quality of life throughout the Great Lakes unless something's done about it.”

It's not just tourist towns that are suffering. So are commercial harbors, like one in Ludington, Mich. -- 100 miles south of Leland. Ludington is one of the 139 commercial and recreational harbors around the Great Lakes. Under new federal regulations issued by the Obama administration, only commercial harbors that handle 1 million tons are eligible for dredging. Today, only 15 of the Great Lakes harbors meet that criteria.

That worries Chuck Leonard, the chief operating officer for Pere Marquette Shipping, which operates car ferries and barges out of Ludington. He is concerned about what low water levels will mean to the amount of tonnage he can ship.

“We're starting to see with our vessel where we're having to light-load, and I'm afraid we could see that increase moving forward,” he said.

For every inch the water level drops, carriers forfeit 8,000 tons of cargo. As loads shrink, the 1 million ton rule becomes harder to meet.

For every inch the water level drops, carriers forfeit 8,000 tons of cargo. As loads shrink, the 1 million ton rule becomes harder to meet.

“We can't get the vessels loaded to where we'd like to, to get them into harbors, the tonnage in the harbors diminishes, and then they become unfundable because the tonnage isn't adequate for the funding. Being in the shipping industry right now is a very frustrating experience,” said Leonard.

Leonard's company pays into a harbor maintenance tax. He and Chuck May think that money should be used for dredging.

“The federal government actually owns these harbors, these channels. And they actually have a tax called a harbor maintenance tax that they put in place the beginning of 1985 to take care of these harbors,” said May. “So far, in the past 15 years, they have collected $8 billion that they have not spent on harbors. $8 billion of this tax, harbor maintenance tax, that they’ve collected and used elsewhere to maintain, or as a façade to cover the deficit. $8 billion would have had all of these harbors in great shape at this time.”

Leonard vents his frustration with the army corps engineer responsible for dredging in Ludington. Tom O'Bryan is sympathetic, but said unless funds are freed up there is little the corps can do.

“It’s sad. I've been working for the corps of engineers for over 30 years, and we've been dredging it for 28 of my 30 years, and it’s a sad day when we have to tell these communities that we don't have the funds to dredge their harbors anymore,” said O’Bryan.

Leland harbor master Dzuba's concern grows as he watches otters play on a beach that shouldn't exist inside the harbor. He said it wasn't always this hard to get dredging paid for.

“We spent the first 40 years in the history of this harbor, the Army Corps dredged it each and every year,” said Dzuba. “Federal funding dried up in 1999, and since then we’ve had to ask for appropriations each and every year. In ’07, the appropriations stopped, so we started fundraising at a local level, and that’s where we are today.”

Leland raised $120,000 last year to pay for dredging to keep its harbor open. But Dzuba said he doesn't know how long the community can support those costs. And scientists predict that lake levels will drop even lower this winter, with ever greater consequences for the 30 million people who live in the Great Lakes Basin.