A Chicago criminologist has new insight into the origins of The Outfit. Robert Lombardo, author of Organized Crime in Chicago: Beyond the Mafia, joins us on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm. Read an excerpt below:

The National Prohibition Enforcement Act ended the sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States. The enactment of Prohibition in 1920 was the result of a one-hundred-year struggle to curtail the use of alcohol by the American public. At the time of the American Revolution, alcohol was seen as the “good creature of god,” an indispensable part of clean and healthy living. It was a regular part of the daily diet and was thought to prevent many diseases. In fact, workmen often received part of their pay in rum or other spirits, and alcohol consumption was common at business and government meetings as well as festive occasions.

Eventually, however, people began to develop an increased awareness of the consequences of the misuse of ardent spirits. Drunkenness was soon recognized as a community problem, and temperance was a common subject of religious sermons. In 1785 Dr. Benjamin Rush, surgeon general of the Continental Army and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, published America’s first scientific inquiry into the use of alcohol. Rush concluded that alcohol had no food value and that it not only aggravated common diseases but was also the direct cause of many.

The emerging temperance movement welcomed Rush’s conclusions. In 1808 the first temperance society in the United States was begun in the state of New York by a young physician named William Clark. Within a decade, a number of temperance societies were established throughout the Northeast. By 1836 eight thousand temperance societies had been formed with an overall membership of more than a million and a half people who openly advocated total abstinence from alcohol. The impact of the temperance movement was also felt in Chicago. By 1844 nineteen hundred Chicagoans belonged to various temperance societies.

Temperance became a means of distinguishing different ethnic groups. Cultural consumption habits pitted “blue-nosed teetotalers” against European immigrants, who regularly consumed alcohol as part of their diet. Germans drank beer; Italians and Jews drank wine. The New England Federalist aristocracy actively used the temperance movement to bolster their declining leadership role. The native American reformers of the mid-1800s saw the curtailment of alcohol consumption as a way of solving the problems of the immigrant urban poor, whose culture often clashed with American Protestantism. The temperance movement became a struggle between rural Protestant society and the developing urban industrial order. Henry Ford, Prohibition’s prime industrial protagonist, saw Prohibition as a great force for the “comfort and prosperity” of America, because it would prevent the wages of his workers from being taken away by the saloon.

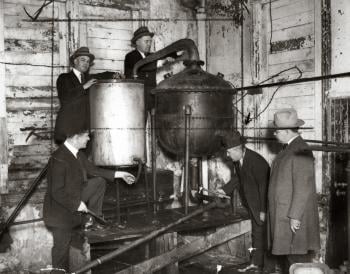

With Prohibition came a demand for illegal alcohol, which the Torrio vice syndicate and other similar groups around the city were in a position to supply. They were well organized and had the political connections to prevent interference from the police. All the concealed agreements made with local politicians over the years, as well as the experience gained through years of struggle against reform elements, were brought into service in organizing the production and distribution of beer and whiskey. Johnny Torrio ran his criminal organization from the Four Deuces Café at 2222 South Wabash Avenue. Torrio is widely believed to have been a no-nonsense businessman who excelled as a master strategist and quickly built an empire that far exceeded Big Jim Colosimo’s.

Torrio’s syndicate was an organization of professional gangsters. It differed from other criminal groups, such as the Valley Gang, in that it was not an outgrowth of a neighborhood play group; its members were from different areas. The gang was formed by adult criminals for the administration of vice, gambling, and illicit liquor. Many of Torrio’s henchmen were seasoned veterans recruited from the various segments of the criminal community. For example, Torrio gangster Marcus Looney, an arsonist and labor slugger, had been a member of the Gilhooley Gang. Anthony “Tough Tony” Capezio and Claude Maddox were recruited from the Circus Café Gang. And James “Fur” Sammons was a former member of the Klondike O’Donnell Gang.

Realizing there was enough money to be made by all, Torrio approached the leaders of Chicago’s other top gangs and suggested they give up burglary, robbery, and crimes of violence in favor of bootlegging. (For personal use, illegal alcohol was poured into a flask and hidden in one’s boot, thus the term bootleg booze.) The return from these traditional practices, he contended, did not justify the risks taken when compared to the profits to be made from smuggling alcohol. The key to success during Prohibition was territorial sovereignty. Each gang would control liquor distribution in its own area and not encroach upon the territory of the others. Many gang leaders agreed to Torrio’s plan, and the system functioned well—for a while.

In 1923 Chicago elected reform mayor William Dever. Dever was a firm believer in the rule of law and quickly ordered the police department to enforce Prohibition. Within weeks of taking office, Dever’s police shut down seven thousand soft-drink parlors and restaurants operating as “speakeasies.” (The word speakeasy referred to speaking softly when ordering.) Dever’s reforms prompted Torrio to move his headquarters to nearby Cicero, Illinois. While Torrio was vacationing in Italy, his assistant, Alphonse “Al” Capone, chose the Hawthorne Inn at 4823 West Twenty-second Street as the gang’s Cicero headquarters. Torrio had brought Capone from New York to work in the Colosimo syndicate. Fearing the spread of the reform wave that had taken control of Chicago, Cicero’s local Republican leader asked Capone to assist the party in the 1924 election.

In return for helping the Republicans maintain control, Torrio and Capone were given a free hand in Cicero. On Election Day two hundred Syndicate gunmen descended on Cicero to ensure that people voted the “right way.” Conditions were so bad that Cook County judge Edmund Jarecki deputized seventy Chicago police officers to go into Cicero and engage the Capone gang. Frank Capone, Al’s brother, was killed in a gun battle with police at a polling station at the intersection of Twenty-second Street and Cicero Avenue. After winning the election, Cicero Republicans kept their side of the bargain. The number of liquor and gambling establishments controlled by Torrio and Capone in Cicero soon grew to 161.

From Organized Crime in Chicago: Beyond the Mafia. Copyright 2013 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press. This material may not be reprinted, photocopied, posted online or distributed in any way without written permission from the copyright holder.