For decades, Chicago city leaders have been trying to forget Al Capone, but a new book keeps his memory very much alive. We talk with the niece of the infamous gangster about her book, "Uncle Al Capone," on Chicago Tonight.

Visit the audio attachment below to hear Al Capone discuss prohibition, read an excerpt from Deirdre Marie Capone's book, and check out some Capone Family Recipes.

![]()

I am a Capone. My grandfather was Ralph Capone, listed in 1930 as Public Enemy #3 by the Chicago Crime Commission. That makes me the grand niece of his partner and younger brother, Public Enemy #1: Al Capone.

For much of my life, this was not information that I readily volunteered. In fact, I made every effort to hide the fact that I was a Capone, a name that had brought endless heartache to so many members of my family. In 1972, when I was in my early thirties, I left Chicago and my family history far behind me, reinventing myself in Minnesota and making sure that no one in my life other than my husband Bob knew my ancestry. I succeeded—even with our four children.

But the truth about who I was hovered at the edges of the reality I had created, and I was terrified of it—terrified of revisiting the shy, wounded girl who grew up friendless, shunned by classmates, forbidden to play with a mobster’s child; terrified of once again hearing those dreaded words, “You’re fired,” and seeing another employer’s doors close to me because of my name; terrified of reawakening the grief of losing both my father and brother to suicide, collateral damage of the Capone legacy; and, above all, terrified that if my children learned they had “gangster blood” running through their veins, they’d be exposed to the same pain I had experienced.

As if this weren’t enough, my silence was also motivated by a little trick of fate truly stranger than fiction. My husband’s uncle married the sister of one of the men killed in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. As you’ll read later in this book, I have good reason to believe that Al Capone was not as responsible for those cold-blooded murders as history has written, but all the same, how could I bring such a terrible complication into our family life? How could I know that my aunt by marriage wouldn’t see her brother’s murderers in my face? This concern was overshadowed because I was more afraid of my children finding out about their ancestry so I kept up the false front.

When my nine-year-old son Bobby came home from school one day in 1974 to announce that his class was learning about Al Capone, it knocked the wind out of me.

Ever since my children started school, I had developed the habit of asking, “What did you learn today?” when they came home. Of course, I always listened to their answers with great interest, but on that particular day, I felt like the whole world had just slid out of focus, leaving only Bobby and me. There he was, smiling and cheerful as always, telling me he was learning about my uncle in his fourth grade class.

My heart seized, but somehow, I managed to get out a half-casual, “What did you learn about Al Capone?” “We learned that he was a gangster,” Bobby told me. He went on to tell me about Prohibition in the 1920s and 30s, Al’s bootlegging operation, and how he had been such an expert outlaw that when the police finally nabbed him, the only charge they could pin on him was tax evasion. I was so astonished that all I could do was nod along as he spoke.

Later that evening, when Bob and I were alone, I told him what Bobby had said. I felt like I had been holding my breath ever since Bobby so innocently chirped the name “Capone.” Bob and I decided together that we couldn’t keep the truth from our children any longer. We had no idea how they would react, but one thing was certain—we didn’t want them to hear about it from someone else, and now that our oldest kids were teenagers, they had started to ask about their grandparents. We couldn’t keep this from them forever.

The next evening, as Bob and I gathered our kids in the kitchen, I was petrified. This was a moment I had created in my head time and again, since Bob and I decided to start a family. And each time I imagined it, it ended badly. I thought our kids would be furious with me for keeping the secret, or for even being a Capone in the first place. Maybe they would be ashamed of me. Or worse yet—maybe they would be ashamed of themselves. Maybe hearing the truth about their family would send them into the same kind of downward spiral that had swallowed so much of my childhood.

When I was growing up, I was often mad at God for making me a Capone. I couldn’t understand why other children weren’t allowed to play with me, and my heart broke every time I heard someone murmur a slur or read the newspapers’ awful accusations about the family I loved—and the family that loved me in return while everyone else shunned me. If these were my prevailing memories of growing up as a Capone, I just couldn’t imagine that things would be any different for my children. As I sat them down at the kitchen table and prepared to break the news, I felt like I was on the verge of crushing the happy life that Bob and I worked so hard to give to them.

I could tell they sensed my nervousness, and they sat unusually quiet as I told them I had something important to say. I squeezed Bob’s hand tightly, and the words came slowly.

“There’s something I want to tell you about my family,” I began. “Al Capone was my uncle. My grandfather was his brother. I was born Deirdre Marie Capone.”

For a split second, there was silence in the kitchen. I could feel my heart in my throat. Then, at the exact same instant, both of my teenagers exclaimed, “Cool!”

In retrospect, I suppose I should have anticipated the reaction, think about what any teenager might say upon hearing they are related to a legend. But to be honest, their excitement was the last thing in the world that I expected. I was so used to hiding and living in quiet shame that it just didn’t cross my mind that my children might be more intrigued than upset.

But of course, it was a different time. I grew up with headlines about the menace of Al Capone’s “Outfit” splashed across the front page. I grew up seeing my classmates’ parents look at me and my family with constant suspicion and fear. I grew up well accustomed to men in dark suits guarding the Capone family home with machine guns. My children, on the other hand, grew up thinking of Al Capone as a celebrity, a folk hero more than a criminal.

As soon as that word, “Cool!” broke the tension in the room, the two younger kids chimed in. Bobby’s eyes grew wide as saucers and, before I knew it, all four of them were peppering me with questions. “What was he like? Was he nice to you? Did he love you? Do you look like him? Do you have pictures?”

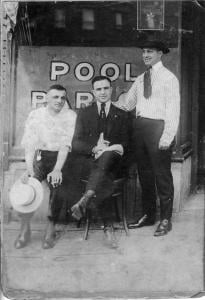

Relief washed over me. I had built this moment up in my mind for so many years, but here I was, discovering that the very source of my shame was now the source of pride for my children. I tried to answer their questions as best I could. I pulled out my family photo albums and began to introduce my own children to the people who loved me most when I was their age.

First, there was Theresa Capone, the mother to Al and my grandfather. She was the rock of the Capones, the woman who held the family together as they emigrated from Italy to New York and then to Chicago. She had known poverty in Brooklyn and the realization of the “American Dream” as Al built his business in Chicago. She raised my father when his biological mother abandoned him, and she acted as a grandmother to me. Her house on Prairie Avenue became the warmest place in the world to me, even with heavy drapes drawn across the windows and armed men stationed at the doors.

Then there were her children. Mafalda—or, to me, Aunt Maffie—was the youngest and the only daughter. Only five years older than my dad, she was more of a sister to him than an aunt. To me, she was a hero and I was her spitting image. Everyone in the family called me “Little Mafalda.”

The older children were six boys: Vincenzo, my grandfather Ralph and his younger brothers, Frank, Al, Mimi, Bites, and Matty. Frank, Ralph, and Al were all involved, to a greater or lesser extent, in earning the family’s keep—which meant operating the Outfit, the organization that distributed liquor illegally during Prohibition. But to me, they were as far from “criminals” as anyone could get. They were loving, funny, larger-than-life men and fiercely proud of me. I could never reconcile the frightening images the newspapers painted of them with the warm-hearted people who teased and joked with me at Sunday dinners.

Finally, there was my dad, Ralph Gabriel Capone. In his short life, he had been the star and the hope of the family. He was keenly intelligent and determined to set out on a different path than his father and uncles. He wanted to make a name for himself with a legitimate business, but the Capone name dogged him and dashed his hopes. Ultimately, he took his own life when I was only ten years old.

Sitting at the table with my children and sharing these memories, some painful and some brimming with joy, was a defining moment for me. For many years, I had delved privately into my family’s history, searching for the line between rumor and truth, and, very slowly, began shedding the thick blanket of shame that came with the Capone notoriety. But to offer this history to my children and to find that they were proud to call it their own was a new step for me. At the age of thirty-four, with the help of my children, I finally accepted myself as Deirdre Marie Capone.

Not only were my children happy to learn of their family ties to Al Capone, they loved to tell people about them. And today, I have fourteen grandchildren who all think of their heritage as a badge of honor. When my granddaughter, Abby, was in the second grade, her teacher made a book for the class in which each student wrote two things about themselves, something true and something untrue, so that the other children could guess which was which. Abby proudly wrote, “I don’t like mustard” and “I am Al Capone’s grand-grand-grand niece.”

Copyright © 2011 Deirdre Marie Capone

![]()

Check out a few of the Capone Family Recipes below.

Al’s Recipe for Italian Beef

3-4 pound rump roast

6 (or more) cloves garlic

½ tsp oregano

½ tsp salt

½ tsp onion powder

¼ cup chopped parsley

¼ tsp crushed red pepper

½ tsp paprika

¼ tsp nutmeg

¼ tsp thyme

6 hard crusted rolls or a loaf of Italian bread

3 red or green peppers

¼ cup olive oil

Hot giardiniera

Preheat oven to 225°. Mix dry ingredients together. Mince garlic. Place meat into a roasting pan and sprinkle with dry ingredients evenly. Place minced garlic on top of meat. Cover roasting pan tightly with cover or foil and place in oven and cook for 6-8 hours.

Wash peppers and slice, removing seeds and stem. Fry them olive oil until limp. After cooking, remove the foil and break meat apart with a fork. Pile on bread and top with fried peppers and hot giardiniera.

Serves 6.

Grandma Theresa’s Ragu

Here is a little known fact. My Aunt Maffie opened a deli on the south side of Chicago after Al Capone’s death. A man who was a regular customer and loved her lasagna came into the deli one day and asked for the recipe for the sauce. Maffie gave it to him, and he used it to create the very first spaghetti sauce of the Ragu Company.

This recipe is enough for one pound of pasta. Most of the time I double it; as it ages well in the refrigerator.

2-28 oz cans of Italian tomatoes pureed

4 tbsp olive oil

6 garlic cloves chopped fine

1 medium onion cut into quarters

1 whole nutmeg

6 basil leaves of 1 tbsp dried basil

1 bulb fresh fennel

1 tsp dried oregano

pinch of salt

¼ tsp fresh ground black pepper

¼ tsp red pepper flakes

Core the fresh fennel and cut into small pieces.

Take a piece of cheesecloth and wrap it around the fennel, onion, nutmeg, and basil, forming a ball that will be lowered into the tomatoes. Heat olive oil in stock pot and add garlic. Stir until the garlic has released its flavor into the oil. Add tomatoes and fennel ball. Bring to a boil stirring slowly. Lower heat and simmer slowly uncovered. Add salt and pepper.

Cook slowly for about 3 hours. Before serving remove fennel ball and discard. This is the only time before serving that we would taste the gravy—we would do it by dipping a piece of bread into the sauce and eating the bread.