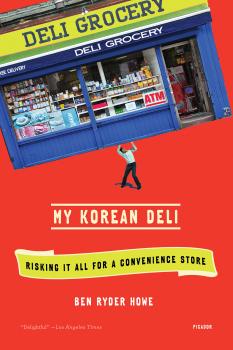

How a high-brow literary editor found himself slicing deli meat and selling lottery tickets at a convienence store with his Korean mother-in-law. We hear from the author of this comical memoir on Chicago Tonight at 7:00 pm when Ben Ryder Howe joins us to discuss MY KOREAN DELI: Risking It All for a Convenience Store. Read an excerpt from the book below.

Steam Table

Fall 2002

Last summer my wife's family and I decided to buy a deli. By fall, with loans from three different relatives, two new credit cards, and a sad kiss good-bye to thirty thousand dollars my wife and I had saved while living in my mother-in-law's Staten Island basement, we had rounded up the money. Now it is November, and we are searching New York City for a place to buy.

We have different ideas about what our store should look like. My mother-in-law, Kay, the Mike Tyson of Korean grandmothers, wants a deli with a steam table, one of those stainless steel, cafeteria-style salad bars that heat the food to just below the temperature that kills bacteria—the zone in which bacteria thrive. She wants to serve food that is either sticky and sweet, or too salty, or somehow all of the above, and that roasts in the dusty air of New York City all day, while roiling crowds examine it at close distance—pushing it around, sampling it, breathing on it. Kay's reason for wanting a deli of this kind is that steam tables bring in a lot of money, up to a few thousand dollars per hour at lunchtime. She also wants a store that is open twenty-four hours and stays open on Christmas and Labor Day. She'd like it to be in the thick of Manhattan, on a street jammed with tourists and office workers.

I don't know what I want, but an all-night deli in midtown with a steam table isn't it. I'm the sort of person who loses my appetite if I walk past an establishment with a steam table. I get palpitations and the sweats just being around sparerib tips. Of course, I don't have to eat the food if we buy a deli with a steam table. I just have to sell it. That's what Kay says she plans to do. But Kay has an unfair advantage: years ago, after she came to America, she lost her sense of smell, and now she can't detect the difference between a bouquet of freesias and a bathroom at the bus station. My nose, on the other hand, is fully functional.

Luckily, I'm in charge of the real estate search, and so far I have successfully steered us from any delis serving hot food. As a result, Kay's frustration is starting to become lethal.

"What's the matter?" she asked me the other day. "You not like money? Why you make us poor?"

These are not unfair questions. I would say that one of my biggest faults as a human being is that I do not love money, which makes me lazy and spoiled. Like finding us a store, for example. Call me a snob, but somehow a deligrocery—a traditional fruit and vegetable market—seems more dignified than a deli dishing out slop by the pound in Styrofoam trays. Is that practical? We are, after all, talking about the acquisition of a deli, not a summer home or a car. If dignity is so important, why not buy a bookstore or a bakery? Why not spend it on a business where I have to dress up for work?

Don't get me wrong: I'm not insecure about becoming a deli owner. I even sort of like the idea. Aside from a few "gentleman farmers," no one can remember the last person in my family who worked with their hands. After blowing off law school and graduate school, after barely getting through college and even more narrowly escaping high school, why would I suddenly get snobbish?

But the truth is, I'm still young (thirty-one is young, right?) and can afford to be blasé. It's like the job I had as a seventeen-year-old pumping gas outside Boston, a gig I remember as brainless heaven. I enjoyed coming home smelly. I enjoyed looking inside people's cars while scraping the crud off their windows. I enjoyed flirting with women drivers twice my age.

Who knows how I would have felt if seventeen were just the beginning, and I could look forward to fifty more years of taking orders from strangers.

Today we are looking at a deli with a steam table. This morning I was informed of the news by a fire-breathing giant, a creature escaped from a horror movie about mutants spawned by an industrial accident, who hovered at my bedside until I awoke with a start, upon which the creature said: For two weeks you be in charge of finding our store, and you not come up with anything. So starting today we do it my way. Then the creature exited, accompanied, it seemed to my half-asleep ears, by the sound of dragging chains.

For the rest of the morning I lie there under the sheets as a form of protest, not intending to get out, until my wife, Gab, sits down on the bed next to me with a cup of coffee.

"I want you and my mother to go together," Gab says. "I can't come because I have things to do at home."

The store is near Times Square and has a name like Luxury Farm or Delicious Mountain. Its Korean owners claim to be making eight thousand dollars a day, a preposterous sum that nevertheless has Kay all excited.

"Don't be afraid of steam table," she says as we drive to the store. "If smelling something stranger, close nose and think of biiig money."

I exhale deeply and try to follow her advice, but instead of fistfuls of cash all I can think of are slabs of desiccated meat loaf slathered in congealed gravy and the smell of boiled ham. So I focus on the drive into midtown—the glowering skyscrapers, the silhouettes of bankers and lawyers behind tinted windows a few stories above the traffic, the gigantic television screens featuring high-cheekboned models talking on cell phones, and at street level my future comrades among the peonage: the restaurant deliverymen, the tarot readers, the no-gun security guards and the DVD bootleggers.

The owner of the deli is a distressingly perky woman named Mrs. Yu. She's frizzy-haired and victimized by an excess of teeth, and she's wearing the Korean deli owner's official uniform: a puffy vest and a Yankees cap settled snugly over her Asianfro. Her age—approximately mid-fifties—is the same as Kay's, which makes her part of the generation of Koreans who came to America in the 1980s and became the most successful immigrant group ever—ever: the people who took over the deli industry from the Greeks and the Italians, the people who drove the Chinese out of the dry-cleaning trade, the people who took away nail polishing from African-Americans, and the people whose children made it impossible for underachievers like me to get into the same colleges our parents had attended.

"My name Gloria Yu," she says when we walk in. "My store make you rich." She winks at me. "Cost only half million dollar."

It seems hard to imagine how any convenience store, even one that can get away with charging twelve dollars for a six-pack of Bud Ice, could be worth half a million dollars, but Gloria Yu's store probably deserves it if any of them do. Like a ship squeezed inside a bottle, a full-sized supermarket has somehow been folded into the space meant for a restaurant or a flower shop. Thousands of items line the shelves, seemingly one of everything. In my general state of paranoia, it occurs to me that if I were to be trapped in this place by some sort of prolonged emergency, such as a flood or a toxic cloud, I could survive for months, maybe even a year, and find something new to eat each day.

"So," Gloria Yu says to me, her voice quivering with excitement, "this your first store?"

"Yes, it is," I confess guiltily.

"I knew it!" she says, practically jumping up and down with excitement. "I knew it! I knew it! You not look likenormal deli owner." A few customers glance nervously our way.

"So where you from?" Gloria Yu asks me.

"Um, Boston."

"Boston? Like the Boston, Massachusetts? No, no, no. No, no, no."

"What do you mean, 'no, no, no'?" I ask impatiently. "That's where I grew up."

"Not where you grow up, where your family from?" Gloria Yu says.

"Oh, you mean originally? Like where are my ancestors from? Here, I suppose. Here as much as anywhere else."

"Hmm . . ." says Gloria Yu, massaging her chin thoughtfully. "Very interesting. Okay, time to show deli!"

Now Gloria Yu thinks I am some sort of freak. Hopefully it will prevent her from selling us her store.

"You two go ahead," I say. "I'm going to wander around alone."

Am I a freak? Why does the steam table scare me so much?

On an even deeper level, though, I wonder, Is fear of the steam table a fear of commitment? A fear of going all the way? Maybe I just need to get it over with and eat a plateful of American chop suey.

"Hey you!" a voice says.

I look around, but there's no one. Kay and Gloria have moved several paces ahead. I'm standing in the drink section, an area filled with glass-doored refrigerators and a rainbow assortment of fluids.

"Hey mister!" the voice commands.

Still nothing.

"Over here," the voice says. "Look inside." And now I see. Next to me, apparently imprisoned within a soda refrigerator, is a balding Korean man in a puffy vest.

"I'm you," the man says, banging meekly on the glass.

"I'm sorry?" I say, yanking the door open. The prisoner stands behind a rack of soft drinks, only his right hand poking through.

"I'm Yu," he says. "Mr. Yu. Store owner. You come to buy store, right?"

"Oh," I say. "Nice to meet . . . you." I speak these words, as far as anyone watching is concerned, to nothing but a rack of soda. (The refrigerator is one of those models that open up from behind, so you can stock the shelves from back to front. Except for his hand, Mr. Yu remains hidden.)

"This store very good," Mr. Yu says cheerily, his hand gesturing dramatically and at one point seeming to lunge straight for my crotch. "Eight thousand a day no problem. You like something to drink?" The hand starts pointing at different flavors. "Which one your favorite? Have any one. Try many different color."

"Thank you," I say to the hand, while taking out a bottle of Code Red. "It's a nice store." Mr. Yu wants to continue the conversation, but before he can, I gently close the door. Then, in an unplanned gesture, I bow solemnly to the walk-in refrigerator.

"Okay, Mr. Original American," says Gloria Yu, coming up behind me with Kay. "You ready to buy my deli?" She winks at me again and says something to Kay in Korean—something evidently quite hilarious, as they both erupt in hysterical laughter.

"What's so funny?" I ask.

"Don't be worrying," says Gloria Yu, adding mysteriously, "You'll be making successful again soon."

"What? Excuse me?"

"Don't be worrying, I said. Success coming! But first, I want to show you something." A devious smile lights up her lips. "I want you and your mother-in-law to come with me so I can show you where this"—she gestures expansively at the steam-table spread, like a game show model unveiling a new car—"is made."

We follow Gloria Yu to the store's basement, where things get dingy pretty fast. The space is cramped, the light dim, and as the temperature starts to climb, the smell of American chop suey becomes as overpowering as a trash can full of baby diapers. In the basement we find a gang of six Mexicans dressed in thick fire-retardant gloves and steel-toed boots—work gear more appropriate to a steelworks than a kitchen. Evidently you don't cook the food that gets served at a steam table. You attack it with extreme bursts of heat from an oven that looks like a smelter. And you don't prepare it, either. You buy it premade from an offsite mass producer of cafeteria and hospital fare somewhere in Connecticut.

The whole experience is rather shocking, and I think Kay feels bad for me. On our way home, I expect the usual barrage of scorn, like sitting too close to a nuclear reactor, but instead she's quiet. And then as we drive over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, the gateway to Staten Island and the traditional summing-up point for any of our family's journeys, she tells me she's changed her mind.

"We need small place, for family only. That one too big. Besides, I'm not really trusting that woman anyway. If store be making eight thousand dollars every day, how come she and her husband still working there?"

A few minutes later we pull into the driveway of our home and find Gab outside. Instead of having just snubbed out a cigarette, which is what she was really doing, she pretends to have been waiting for us. She does have news, after all.

She bends over and sticks her head through the passenger window, maintaining just enough distance so that we won't smell the smoke on her breath.

"I found the perfect store," she says.

It wasn't my idea to buy a deli. The idea came to my wife at the time of her thirtieth birthday. Thirty can be an uncomfortable turning point for those inclined to measure their own accomplishments against those of their parents. Gab took it especially hard.

"What have I done with my life?" she asked me.

I reminded her that she had graduated from one of the best colleges in the world (the University of Chicago, where we met almost ten years ago) and obtained both a master's degree and a law degree. She'd even had a burgeoning career as a corporate attorney at a Manhattan law firm, until she'd decided to chuck it all so she could open this deli for her mother.

"And?" she retorted angrily. "Do you know what my mother had accomplished by the time she was thirty? She had three kids who she had raised with no help from my father. She had her own business, which she ran by herself. And she was about to immigrate to America, a country she knew nothing about. All by thirty!"

I thought of reminding Gab that her mom never finished college—Gab was beating her three to none in the degree category—but it didn't seem like what she wanted to hear.

Over the course of the next few months, Gab's thirtieth-birthday paranoia transformed into an obsession with repaying her mother's sacrifice. Mistakenly, I had thought that she had already done that by being successful herself. But as the year went on, it became clear that Gab would not be satisfied without a sacrifice of her own. So her goal became to give back some of what Kay had given up in coming to America.

She was going to give her back her business.

And sacrifice her husband.

Kay's old business had been a bakery serving typical Korean desserts. She spoke of it so lovingly one wondered how she had ever coped with its loss. However, unless Americans suddenly developed a taste for mung bean balls and glutinous rice cakes, doing the same kind of business was not going to be an option. Kay knew how to run a deli, having twenty years of experience clerking at 7-Elevens and Stop'n Gos across America. Yet she was no longer the same person she had been in her twenties. Though still frighteningly strong at the age of fifty-five (her one weakness being an inability to say no to relatives requesting favors), she was now prone to thunderous physical breakdowns that left her bedridden for days. And the breakdowns were getting longer and more thunderous. She still smoked, she ate terribly, and she invariably found ways to get out of the doctors' appointments her children tried making for her.

Moreover, physical health was not the only issue. America had wrought some mysterious changes, like the loss of her sense of smell. And there was the question of why she'd never returned to owning her own business. Was she scared? Intimidated? Had she lost her nerve? Or had she lost the desire and the drive? Was she possibly depressed? No one knew, because Kay would no more discuss her feelings than she would go to a doctor. (She had no trouble exhibiting them, but discussing them was out of the question.) Due to her complex psychology, it was possible, of course, that she was all of those things. However, the only obvious reason why she hadn't opened a store was money.

You need money to start a business, and Gab and I, around the time of her thirtieth birthday, were enjoying, for the first time in our married lives, having just a little money in our bank account. It was money we guarded with insane desperation, not even telling each other how much was in the account. The very act of saving was new to us, like a magic power we couldn't quite believe we had acquired. But even more important, it was that money and that money alone that would eventually buy our freedom from Kay's house on Staten Island.

We had moved into the basement nine months before, after the lease on our Brooklyn apartment expired. After living in Brooklyn for three years, we had tired of paying rent to our landlord, a former ad executive from Parsippany who had miswired our brownstone so that everything blew up in our faces. We wanted to own our own space and there were thoughts of starting a family, and when the lease ran out we decided it was time. Kay's house was to serve as a temporary refuge while we house-hunted.

Deep shame attended our moving into Gab's mother's household, but it was not as bad as moving to Staten Island, New York City's pariah borough, a place where once-hot trends like Hummers and spitting go to die, a place so forsaken that not even Starbucks would set up a store there, nor even the most enterprising Thai restaurant owner—only immigrants from the former Soviet bloc, people fleeing environmental disasters and the most involuted economies on earth. (Perhaps they found something homelike in the smoldering industrial landscape, a familiar scent in the air.) As Gab and I quickly discovered, friends were uneasy about visiting us in our new borough. "Can you smell the dump where you live?" they would ask. "How long does it take to develop a Staten Island accent?" We promised they wouldn't have to go back to Park Slope wearing velour sweat suits or smelling like garbage, but still they wouldn't visit us.

Our bedroom was in a basement. It had exactly one window, a shoe box–sized portal at ground level that occasionally allowed us a clean, unobstructed view of an ankle. One of our neighbors had a bored old house cat who used to come and sit in the one window and watch us undress. Probably he wondered what kind of deranged animal chose to live its life underground, watching people's ankles. Above our heads, clomping around day and night, were relatives of Gab's who'd recently made the trip from Korea and were as surprised to see us as we them. "We can understand living with your parents in Korea," they said, "but America is a very big country." Some of them stayed with us for months, squeezing three at a time into beds made for one. Some of them were new immigrants who spoke no English at all, but it didn't matter in Kay's house because the television was forever playing Korean soap operas, and the radio was constantly tuned to Korean talk radio, and the refrigerator was filled with bean sprout soup, sea slugs and fermented cabbage. I was the only one for whom it mattered, because I did not eat Korean food and could not speak a word of Korean.

Gab and I had no sex at all for the first three months. Too dangerous. In an Asian household no one wears shoes indoors, so you never hear anyone coming. And since the general rule in the Paks' house was that an unworn shirt was your shirt, an uneaten chicken leg your chicken leg, people were always barging into the basement hoping to get into our bed.

From the day we moved in, we were dying to get out, which gave us the power to save thirty thousand dollars in less than a year. But then came Gab's thirtieth birthday, and suddenly our misery didn't matter anymore—in fact, the greater our misery, the better Gab felt. "Don't worry," she said to me. "We'll still be able to move out." She had a plan. At first, she and I would be the owners of whatever store we bought, and Kay would be the manager. During this period, we would keep the store's profits and use them to replenish our bank account. Later on, within the six months or so it would take for the business to stabilize, we would transfer ownership to Kay and resume our old lives.

This plan was so foolhardy, so pregnant with the seeds of its own destruction, that it was almost as if it had come from me, not Gab.

Gab's "perfect" store is in Brooklyn, a borough that, while beloved by many, stirs nothing in the heart of Kay, or that of anyone else in my wife's family, for that matter. For the Paks, Brooklyn is nothing but a sprawling, dirty, dangerous place with no Korean restaurants or supermarkets and none of the prestige or business opportunities of Manhattan. Except to go the airport or endure a passage on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the borough has no place in their lives.

"The store is owned by North Koreans," Gab reports gleefully. This is excellent news because training in the Kim Il Sung school of neo-Stalinist entrepreneurship tends to put one at a fairly severe competitive disadvantage, and we have hopes that the store will be undervalued.

Nothing, however, could have prepared us for the spectacle we were about to witness. While the store is in a trendy neighborhood surrounded by restaurants with one-word names and menus offering eleven-dollar desserts, the store itself—well, I've seen hunting cabins in the woods that were better stocked. The shelves are all but empty, and the place looks like it has been bombed, judging by the rubble swept into the corners and the tattered awning fluttering in the stiff November wind.

The owners, an older couple and their two silent daughters, are extremely friendly, but things only get weirder after we meet. "Country people," Kay whispers to me as they lead us on a tour. They are like human beings from a different century, and they have funny accents and use words that Kay and Gab don't understand. Both have numerous missing teeth and haircuts they've obviously given themselves.

The store embarrasses them, and they apologize for it, offering to feed us as compensation. "Come," they say, leading us to the kitchen, where a mysterious crimson broth burbles and seethes inside a blackened pot. "No, thank you," we all say. Next to the stove I see a box of broken-down fruit crates, tree branches and other bits of scrap wood. Gab goes off to use the bathroom and returns wearing an alarmed scowl, having peed in a makeshift closet with only duct-taped cardboard for walls. This place has secrets. I begin to feel like an intruder. And then we ask to be shown the basement.

The owners look at each other nervously. "Okay," says the husband. "Follow me."

It's nothing to be ashamed of, really—just violently at odds with the city health code. The owners (or somebody; we don't ask) turn out to live in the basement, where there are beds, dressers and clotheslines hung with wet laundry. Being basement dwellers ourselves, Gab and I withhold judgment, but Kay is appalled. It looks like the power has been cut off recently, judging by all the candles, and I assume that the kindling I saw by the stove is what they've been using to heat themselves. Then suddenly a loud noise fills the basement, vibrating like an earthquake, and a subway car goes by right on the other side of the basement wall.

"Bet that keeps you up at night," I say to the male owner.

"Bet what does?" he replies.

We go back upstairs and take another look. The store is a full-blown disaster—during the twenty minutes we've been visiting, not one customer has come in—but with work it can be turned around, and outside waits a fancy neighborhood filled with big spenders. The owners want seventy-five thousand dollars, which we offer them; then we wait for their response. Nothing happens for several days. We have now been looking for a store for three months, and patience in the Pak family has truly all but run out.

"How hard can it be?" Gab exclaims. "Is New York City not filled with delis? We aren't looking to open a whole supermarket. All we want is our own little space."

"Maybe it's a message," Kay says. "Buying store is mistake."

But we've already considered the alternatives, such as a Subway or a twenty-four-hour photo shop or a fishmonger's, and ruled out each one, because the Pak family's expertise lies in convenience stores.

Then the owners of the Brooklyn store call. They tell Gab they've decided not to sell after all and, in keeping with their mysterious ways, offer us no explanation. Perfectly polite and friendly, but perfectly strange at the same time. In a month or so we will drive by their business, just to see if they were telling us the truth, and we will confirm that indeed it has not been sold, but neither is it open. The place is dark and shuttered. A little after that Kay will hear through the Korean grapevine that the old man had suffered a heart attack and the family had moved to parts unknown.

"Now what we do?" Kay says in disgust. "I'm not be having energy anymore. This drive me to be the crazy person."

We all look to Gab, who is slumped on the living room couch and seems in fact to be sinking into it, sucked down by some depressive force emanating from below the house. She says nothing for a while, but then:

"I can look at one more store," she says. "Just one. After that I'm finished."

Kay gets the Korean newspaper, and there in the classifieds it is: "Busy street, bright store, new refrigerators—Brooklyn. $170K."

That was how we found out about Salim's store.

Excerpted from My Korean Deli by Ben Ryder Howe, Copyright 2011 by Ben Ryder Howe, Published in 2011 by Henry Holt and Company. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

Visit the Audio Attachment below to hear an interview with the author.