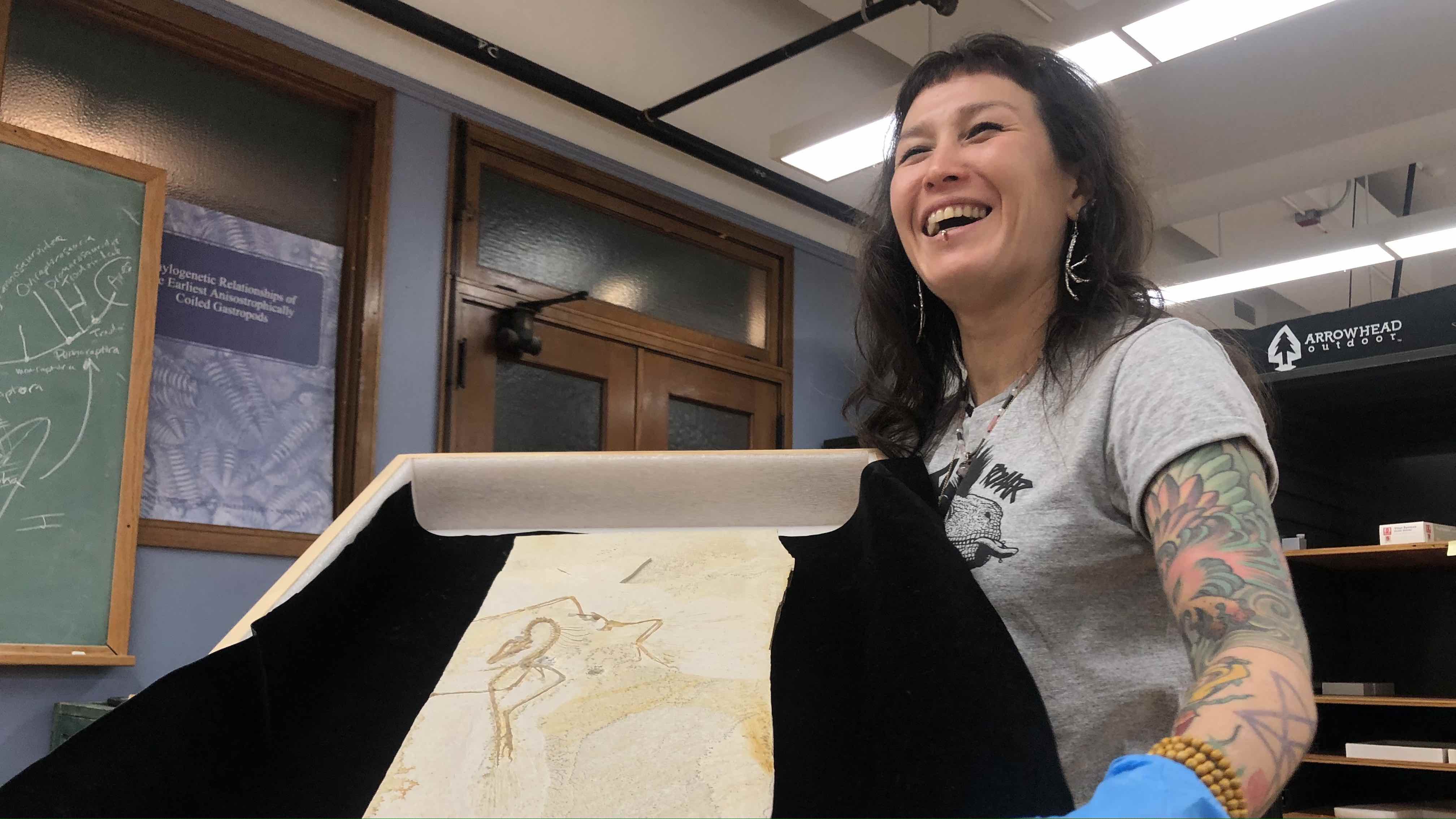

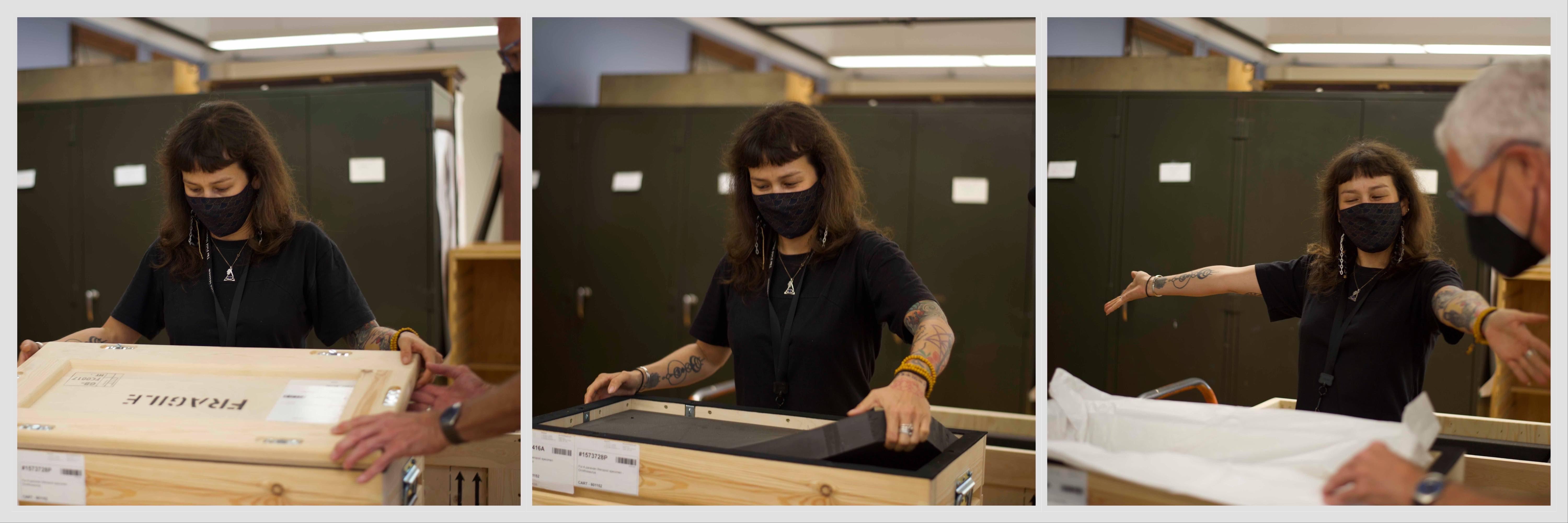

In August 2022, a delivery van rolled up to Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History and offloaded a single item — a crate marked “fragile.”

Jingmai O’Connor, associate curator of fossil reptiles, was there to take receipt, and after a bit of a scramble to locate a dolly, she maneuvered the shipment onto the Field’s freight elevator, rode up to the Geology Department, and wheeled the precious cargo down the hall — cringing at every bump in the flooring. A roomful of hastily assembled colleagues were waiting, eager to catch a glimpse of the mystery treasure.

Thanks to our sponsors:

Whatever big reveal O’Connor may have envisioned was comically delayed by the sender’s elaborate packaging.

“It came in this sarcophagus that looks like something from ‘Indiana Jones,’ like a box within a box. So we’re unscrewing it, we’re opening layer after layer,” O’Connor told WTTW News.

But eventually she hit paydirt.

After pulling back one last flap of tissue paper, O’Connor finally had her “ta-da” moment, introducing the “Chicago Archaeopteryx … the most important fossil ever.”

That’s quite a statement coming from a curator at the Field, home of the mighty T. Rex, Sue. But what Archaeopteryx lacks in size, it makes up for in significance as a “transitional” species that essentially proved Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Jingmai O’Connor unboxing the Chicago Archaeopteryx in August 2022. (Courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History)

Jingmai O’Connor unboxing the Chicago Archaeopteryx in August 2022. (Courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History)

On Monday morning, more than 18 months later, the Field Museum repeated the unveiling, only this time with fewer hiccups and to greater fanfare.

In front of gathered dignitaries and the press, the Field formally announced to the world what had become a not-so-well-kept secret: The museum had acquired just the 13th specimen known to exist of Archaeopteryx (ar-key-AHP-ter-icks), a fossil often described as the “missing link” between dinosaurs and birds.

“It’s a spectacular example ... teeth like a dinosaur, a tail like a dinosaur, but it’s a bird,” said Julian Siggers, Field Museum president and CEO. “The top-level message is that dinosaurs didn’t go extinct, they actually evolved into birds.”

The Field Museum has acquired the 13th known specimen of Archaeopteryx, often called the “missing link” fossil between dinosaurs and birds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The Field Museum has acquired the 13th known specimen of Archaeopteryx, often called the “missing link” fossil between dinosaurs and birds. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The acquisition is a coup not just for the museum and O’Connor, but for Chicago, with the Field becoming the only public institution outside of Europe to have an Archaeopteryx in its collection.

“It’s definitely the most important scientific specimen we’ve ever acquired, beyond a doubt,” Siggers said. “It takes first place. … For us here, it’s an enormous opportunity for science. But there was an incredible exhibition opportunity, too. Because it’s then on us to explain to the public why this is so important.”

For the “why,” let’s travel back to 1860, but first, a quick time jump way back to the Mesozoic Era.

An illustration of what Archaeopteryx may have looked like. (Courtesy of the Field Museum and Ville Sinkkonen)

An illustration of what Archaeopteryx may have looked like. (Courtesy of the Field Museum and Ville Sinkkonen)

During the Mesozoic Era (roughly 252 to 66 million years ago), dinosaurs ruled the earth, Archaeopteryx among them.

Picture this chicken-sized creature going about its business, living in a prehistoric archipelago covering what is now Bavaria in Germany, a landscape that at the time was dotted with islands and stagnant lagoons.

Occasionally bodies of Archaeopteryx — along with plenty of other creatures — would fall or get swept into one of these lagoons. There, these organisms would sink to the bottom and settle in the muck undisturbed, thanks to water so lacking in oxygen that it couldn’t support any kind of life, including scavengers.

The lagoons no longer exist, but the accumulated mud and organic matter eventually compacted into limestone, containing exquisitely preserved fossils of those long-dead creatures.

All of the specimens of Archaeopteryx unearthed to date — including the Field’s — have come from this single deposit of Bavarian rock, known as Solnhofen Limestone.

The first Archaeopteryx fossils were excavated around 1860 (exact dates of a fossil’s discovery versus its announcement versus its identification are often murky). The timing couldn’t have been more serendipitous, occurring shortly after the publication of Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking “On the Origin of Species,” the foundational text of evolutionary biology.

Darwin knew the biggest criticism of natural selection, his theory of evolution, would be the lack of supporting proof. There had not, as yet, he admitted, been a single discovery of a fossil demonstrating an organism’s gradual change from one form to another.

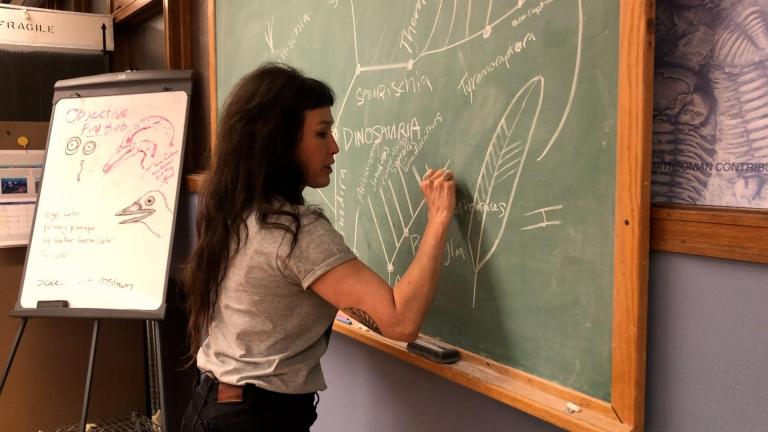

“He points out, in the first edition of his book ... we have no transitional forms or missing links that we can point to and go ‘Boom, right there,’” O’Connor said. “And then two years later Archaeopteryx is found. It’s the perfect missing link.”

“If you needed something to prove you right ... there was nothing that could have been better than Archaeopteryx,” she continued. “At the time, the only animals we knew with feathers were birds, and it’s got feathers. And not only does this have feathers, it has feathers forming wings that look fairly close to a modern bird’s wing. So you’re like, ‘Bird.’ But then the skeleton, there’s almost nothing bird-like about it. Nothing. It’s got this long reptilian tale, it’s got teeth, there’s no sternum, no breastbone.”

To a paleornithologist like O’Connor, whose specialty is the study of the evolution of fossil birds, Archaeopteryx is akin to the Rosetta Stone, a legendary rock star fossil that’s an icon of paleontology and evolution itself.

She has, in the course of her career, viewed several of the other Archaeopteryx specimens, often just through exhibit glass. Those that are made available for research are limited in terms of what a scientist is allowed to probe, so to have a specimen of her own to study is the equivalent of a moonshot.

“I wouldn’t say it’s like a dream come true, because I never would have thought to be like ‘Oh, I hope that one day I can have an Archaeopteryx,’” O’Connor said. “That’s just beyond the realm of reasonable hopes and dreams.”

How a specimen more or less fell into her lap is a tale filled with twists and turns.

Preparators at the Field Museum spent 1,200 hours painstakingly clearing away rock from the Archaeopteryx’s fossil bones. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

Preparators at the Field Museum spent 1,200 hours painstakingly clearing away rock from the Archaeopteryx’s fossil bones. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

“About six years ago, I first learned there is an opportunity that there is an Archaeopteryx, or what probably could be an Archaeopteryx, out there,” recalled Thorsten Lumbsch, the Field Museum’s vice president of science and education.

Though Lumbsch’s background is in botany, with a specialization in the study of lichen, he immediately grasped what acquiring an Archaeopteryx specimen could mean for the Field, both for its researchers and for its visitors.

“It’s the one object that, like almost no other object, shows the evolution of life and in this specific case, the evolution from one very popular group of organisms — dinosaurs — to another very popular one, which are birds,” Lumbsch said. “And I think therefore it is a great example that is easily understandable for the general public. As much as it’s scientifically important, I think it is also a great object for education and outreach because it connects these two iconic groups of organisms.”

The question wasn’t so much did the Field want the specimen, but could it get it? The process of acquiring a rare and valuable fossil is always fraught with complications, but with Archaeopteryx, there are additional degrees of difficulty.

While the first Archaeopteryx specimen wound up in London, the rest are almost exclusively held by German institutions; indeed laws on the books today don’t even allow Archaeopteryx specimens out of Germany. The only other specimen housed outside of Europe is the Thermopolis Archaeopteryx, on long-term loan to the privately owned Wyoming Dinosaur Center.

The Field’s potential fossil was in Switzerland, in the hands of private collectors, having left Germany before the aforementioned rules were enacted.

“You have to do provenance research to make sure it has left the country when it said it did, and the chain of ownership,” Siggers said. “When we got very serious about acquiring it, then we really had to look at it very closely, and we were satisfied.”

‘It’s the one object that, like almost no other object, shows the evolution of life.’

Then, as negotiations proceeded — slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic — and fundraising efforts got underway, a bit of kismet occurred.

“There was this very happy coincidence that we were searching for a new curator of dinosaurs, and Jingmai O’Connor applied,” Lumbsch said. “At the time, I didn’t know if we could really achieve and get the (Archaeopteryx) specimen ... really the stars aligned — having Jingmai as a scientist who really focuses on early evolution of birds, this transition from dinosaurs to avian dinosaurs if you will, and you have this object that is ... really a great tool, a toy to play for the scientists.”

O’Connor, spoiler alert, got the job and even before her official start date in fall 2020, the Field put her on a plane to Europe to clap eyes on the specimen.

“This deal being brought to my attention, I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, how exciting,’” O’Connor said. “But the acquisition ended up taking, I think, two more years almost. So it was a really long, drawn-out emotional roller coaster for me. There were periods where I thought the deal was falling through and we weren’t going to get it, … moments where I lost hope. It was really up and down. It was such a nail-biter.”

On the day the specimen finally arrived in Chicago, packed in its “sarcophagus,” the Field still wasn’t sure what exactly it had purchased. (The museum is remaining tight-lipped on the amount it paid, which was raised through donors.)

You see, much of the fossil’s particular appeal lay in the fact that the specimen was “unprepared,” or still contained in its original slab of rock (which scientists call “matrix”). This meant no one else had worked on it, and the Field would have complete control over and knowledge of every aspect of the specimen’s preparation.

“All the other specimens of Archaeopteryx that are known that are out there, they are prepared, flat, everything prepared,” Lumbsch said. “And some of them were prepared 100 years ago when the techniques were a little bit coarse, or details might be lost.”

On the flip side, “unprepared” also meant the Field had no idea whether the slab contained anything other than the bird’s arms, which had been exposed during its quarrying. Of the dozen previously announced Archaeopteryx fossils, only three are relatively complete and several others are composed of fragments. One is so incomplete that it’s been nicknamed “chicken wing.”

“That could have been what we were acquiring,” Siggers said. “Exactly the condition it (the specimen) was in was a bit of a gamble, to be honest. But in the end it was a sort of informed roll of the dice.”

The suspense weighed on O’Connor, dampening a bit of the delivery-day excitement.

“It was really stressful for me, so much pressure,” O’Connor said. “People are like, ‘Is it going to be worth it?’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t know.’”

Shortly after her “ta-da” moment, O’Connor took the slab to the Field’s in-house X-ray lab and got her answer.

Video: Field Museum staff cheers as an X-ray reveals their just-arrived Archaeopteryx specimen is one of the most complete ever discovered. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

“Everybody’s crowding into this tiny little room and we have our GoPros and our camcorders,” O’Connor recounted. “We’re recording this whole thing because this is an important historical moment for the Field Museum. … And we’re all staring at the computer screen that’s going to show us this image.”

“So this whole skeleton showed up really, really clearly on the X-ray,” she continued. “Just, boom, there. It was the complete thing, and it was oh so exciting. But also I’m going to say an enormous relief.”

The gamble had paid off, and then some.

“As luck would have it, it turns out to be one of the best, if not the best, that you could get,” Siggers said.

Birds — and that includes Archaeopteryx — have hollow bones with thin walls that, even in complete specimens, are typically crushed as they’re compacted, making it difficult to determine their shape. In fact, the Field’s code name for its fossil was “Crushed Bird.”

But the X-ray showed some of the most perfectly preserved bones ever found in an Archaeopteryx, including a beautiful skull — “Hands down we have the best skull of them all,” O’Connor said — and never-before preserved neck bones.

“If you look up papers that write about Archaeopteryx, they’re like, ‘Yeah, we basically don’t really know anything about the neck vertebrae,’” O’Connor said. “And in fact the entire spinal column is very poorly known. Ours has that in almost perfect three dimensions. This specimen far exceeds my wildest expectations.”

All of that detail, it should be noted, was still encased in rock.

It would fall to a pair of seasoned fossil preparators at the Field to scrape away the limestone and truly reveal the Chicago Archaeopteryx.

The unprepared Archaeopteryx fossil, from left; Akiko Shinya and Connie Van Beek get their first glimpse of fragments with Jingmai O'Connor; Connie Van Beek takes a closer look at the just-arrived specimen in August 2022. (Courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History)

The unprepared Archaeopteryx fossil, from left; Akiko Shinya and Connie Van Beek get their first glimpse of fragments with Jingmai O'Connor; Connie Van Beek takes a closer look at the just-arrived specimen in August 2022. (Courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History)

Akiko Shinya and Connie Van Beek have 20-plus years experience each preparing fossils, a career for which there is no formal educational program.

“Most of us come from on-the-job training,” said Shinya, who has a geology degree. Van Beek, by contrast, studied fine arts and is a former music producer who started trekking along on dinosaur digs in her free time.

“To me, fossil prep is the blending of art plus science,” said Van Beek. “The art is already there and you are revealing it, you are revealing it for science.”

The two have worked on almost every type of fossil out there, from animals to plants, embedded in nearly every kind of rock. But Archaeopteryx was unique in a number of ways.

Neither woman had experience with Solnhofen Limestone, so the Field brought in an expert who works exclusively with the rock to help at the outset. He introduced Shinya and Van Beek to new tools and techniques capable of carving through the tough, brittle limestone without damaging the bird’s bones.

“A lot of fossils are preserved in mudstone that’s pretty soft and you just use a little pick,” O’Connor explained. “This rock is really hard, so you have to use something that’s pretty aggressive.”

“Aggressive,” in the context of working on such a rare fossil that was also incredibly fragile, was daunting to say the least.

“I had worked on fossil birds before but none that had this degree of fragility,” said Van Beek, who likened the specimen’s bones to eggshells.

“The fact that it’s so rare made the anxiety level creep up,” Van Beek said. “You’re praying, ‘I hope I don’t break anything, I hope I don’t break the tip.’ It was kind of terrifying the first, I’d say the first couple of weeks, before you just finally found your footing and then let’s just do it ... do your best.”

Their work on the specimen began in earnest in January 2023, using a CT scan of the fossil as a “map” of where to delve and what to expect. Each step along the way, as they revealed more and more of the bird, has been documented in a three-ring binder that contains photos and reference notes, a level of detail that will assist anyone working on the specimen in the future.

A closeup of the Chicago Archaeopteryx skull. (Courtesy of Field Museum of Natural History)

A closeup of the Chicago Archaeopteryx skull. (Courtesy of Field Museum of Natural History)

O’Connor was in frequent consultation, occasionally requesting to have a bit more rock stripped.

“They also saved every tiny little fragment of bone,” O’Connor said. “In some cases they could have put it back on but I was like, ‘No, no, keep that for me,’ because these little tiny fragments of bone we can use for histological analyses, which can tell us about how it (Archaeopteryx) was growing.”

Together the three agreed when to call it quits on further exposing the fossil, some of which, for the time being, remains hidden in the rock, including a layer of feathers.

“You have to expose what’s safe for the specimen,” Shinya said. “It is better to not damage the specimen than try to expose even more. You never know, maybe 20 years from now, maybe a new technology or method comes up and maybe they’ll be able to successfully remove something to expose the other feather layer.”

Between them, Shinya and Van Beek spent 1,200 hours working on the fossil, staring through a magnifying scope and scraping away at rock.

There are many who might consider the work tedious — it’s a common comment Shinya and Van Beek hear from museum visitors — but the two say fossil prep is anything but.

“We are revealing something that has not been seen for so long,” Shinya said. “It’s been 150 million years, we are the first ones to actually see those fossilized bones. That’s pretty exciting.”

Now, with the public unveiling, the preparators’ superb skill is on full display, all the “insane, exquisite little details” they preserved, according to O’Connor.

And while Shinya and Van Beek’s time with Archaeopteryx is essentially complete, it will continue to reap research rewards for O’Connor, whose work in many ways is just beginning.

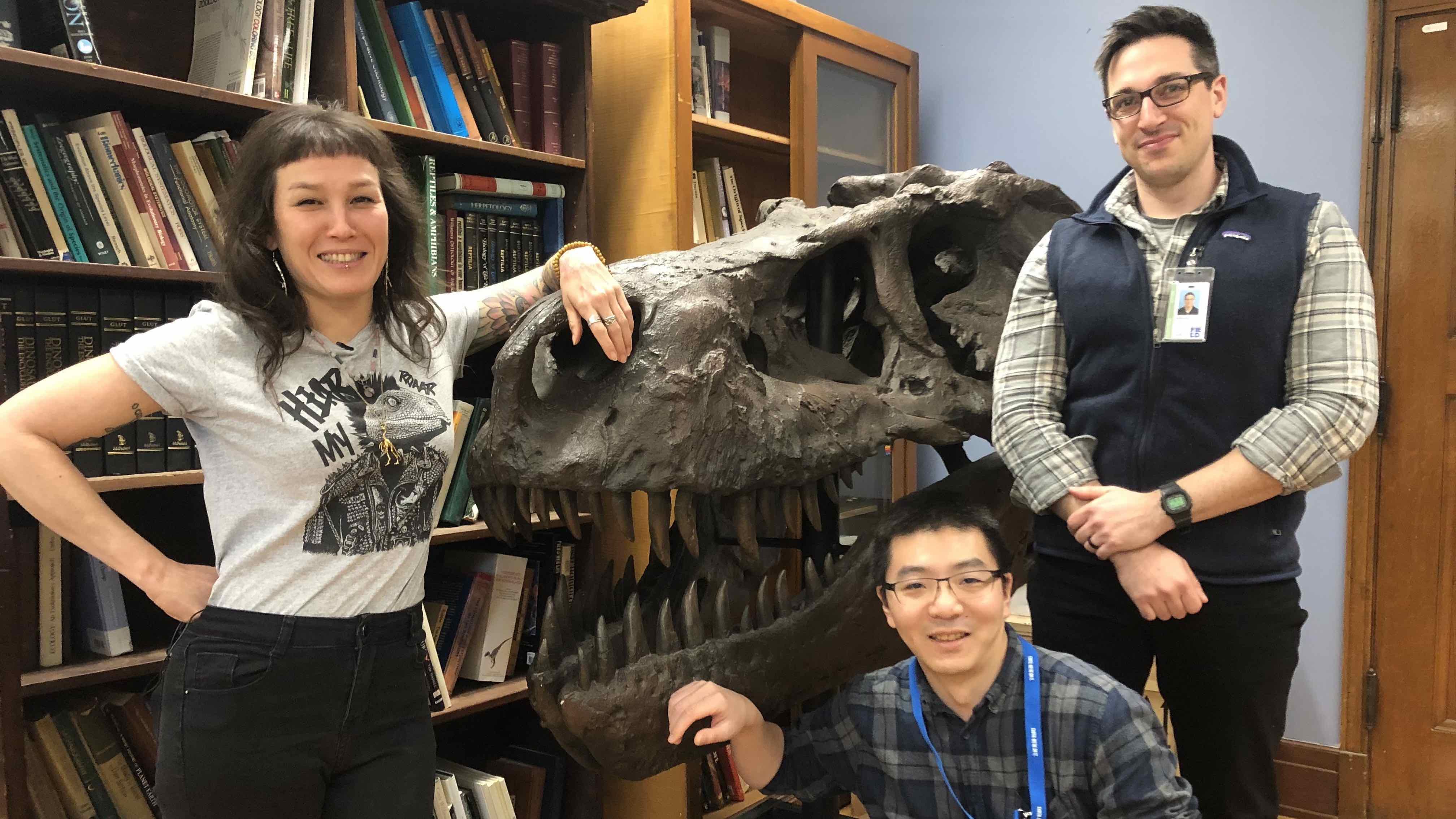

Jingmai O’Connor, left, with lab assistants Pei-Chen Kuo, front, and Alexander Clark. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Jingmai O’Connor, left, with lab assistants Pei-Chen Kuo, front, and Alexander Clark. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Alexander Clark, a Ph.D. student who’s been assisting O’Connor in the lab, was given the unenviable assignment of examining the palates of birds in the Field’s vast collection for comparison with Archaeopteryx.

The smell of preservation fluids still lingers in his nostrils’ memory, but he wouldn’t trade the noxious experience for anything.

“‘Surreal’ is the word I keep coming back to,” said Clark. “I couldn’t have imagined we would have gotten this specimen. I’m so nervous around it — it’s irreplaceable.”

At times, postdoctoral assistant Pei-Chen Kuo said he has felt like he’s in a dream. He’s been working on the CT scan segmentation, creating a 3D image from countless individual scan “slices.” (The Field will make these scans and models available to other researchers.)

“Most (Archaeopteryx) specimens are pretty flat, and there’s no good skull,” said Kuo. With Chicago’s, “Oh my god, everything is there.”

In advance of Monday’s announcement from the Field, O’Connor and her team have already raced to submit three research papers for publication (Shinya and Van Beek received co-author credit for their invaluable prep work), and that’s just the tip of the Archaeopteryx iceberg.

“This fossil is definitely going to keep us busy for a long time,” O’Connor said.

There’s so much to learn, she said, because even though the first Archaeopteryx specimen was identified more than 160 years ago, and its importance is almost unmatched, its fossils haven’t been well studied to date.

Infinitely more work has been done on T. Rex, for example, which, O’Connor likes to point out, is an “evolutionary dead end. Yeah, it was pretty cool, but then it just goes extinct.”

The University of Texas has one of the best CT scanners in the country, so that’s where the Field Museum took its Archaeopteryx specimen for a photo session. The images will help researchers create a 3D model of the fossil. This information will be made available to scientists outside the Field, part of the museum’s commitment to furthering study of the species. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

The University of Texas has one of the best CT scanners in the country, so that’s where the Field Museum took its Archaeopteryx specimen for a photo session. The images will help researchers create a 3D model of the fossil. This information will be made available to scientists outside the Field, part of the museum’s commitment to furthering study of the species. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

The reasons for the dearth of knowledge regarding Archaeopteryx are myriad.

For one, the understanding that “birds are dinosaurs” really only became widely accepted in the 1990s, which is when Archaeopteryx became more interesting to paleontologists, O’Connor explained.

Then there’s the matter of the scarcity of specimens, most of which are incomplete.

On top of all the questions for which scientists have no answers — like what did Archaeopteryx eat? — what is known about the creature is often hotly debated: Which group of dinosaurs does Archaeopteryx belong to? Could it actually fly? If so, how?

“People just argue about this for decades and decades,” O’Connor said.

Some of this uncertainty is inherent in paleontology, which the public doesn’t always appreciate or recognize.

“We’re working with such incomplete information,” O’Connor said. “Think about an organism — look at our bodies — and then reduce us to just a skeleton. … But then you don’t even usually have a complete skeleton. There’s a lot of unknowns.”

With Archaeopteryx, these issues are compounded by its “icon of evolution” label.

“Because of all these really pivotal and critical positions that it supposedly holds relative to our understanding of the evolution of birds and the evolution of flying dinosaurs, this makes it really controversial and makes people more argumentative about the details,” O’Connor said. “So even though this fossil has been known for a very long time, there’s very little that people agree on.”

She aims to tackle some of those lingering mysteries, including one of the biggies: Could Archaeopteryx fly?

“We’re collaborating with somebody who’s a specialist in biomechanics and we’re giving them our 3D models to try to do some analyses to see if it could fly,” O’Connor said. “Whether or not Archaeopteryx could fly, not only is it central to whether or not it’s a bird, it’s also really important for us to understand how flight evolved in dinosaurs.”

Video: A scan of the Field Museum’s Archaeopteryx fossil revealed incredible new details. (Courtesy of the Field Museum)

There are those who might question why it matters what a 150 million-year-old creature had for breakfast or how it moved about its prehistoric world.

O’Connor has a ready reply: “Archaeopteryx is the earliest piece of information that we have regarding one of the biggest evolutionary success stories of all time.”

Birds. She’s talking about birds, and birds as dinosaurs.

“Because dinosaurs are currently the most diverse group on our planet — in terrestrial environments,” O’Connor said. “On land, birds are the most diverse group of vertebrates. So yeah, this is the beginning of that story, that evolutionary success story.”

Studying how birds not only evolved, but survived the mass extinction that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs couldn’t be more timely.

“We are a planet in crisis, we are a civilization in crisis, and we desperately need information to guide us through this crisis,” O’Connor said. “So studying why this one group of dinosaurs or this one subset of this one group of dinosaurs survives is actually very relevant. Paleontology ... is absolutely relevant to the most pressing concern that humanity is facing at this moment.”

O’Connor makes a compelling case for why the public should care about Archaeopteryx. But will the old bird sell tickets?

That’s the challenge for the Field. Because Archaeopteryx isn’t just a scientific specimen, it’s an exhibit. And for crowds accustomed to Sue the T. Rex — arguably the museum’s biggest draw — the “exquisite details” of Archaeopteryx, visible only with the aid of magnification, might fall short.

It’s hard to know what to expect in terms of public reaction, said Siggers, who has a Ph.D. in archaeology.

He’s admittedly not the best gauge, having grown up in London visiting the city’s Natural History Museum, home to the original Archaeopteryx specimen. “As soon as I became interested in it, I found out how important it was,” Siggers said.

Coincidentally, Lumbsch, it turns out, grew up in Frankfurt, Germany, where Archaeopteryx is “a big thing,” he said. “Of course I heard of it.”

But when O’Connor polled some of her anthropology colleagues at the Field, Archaeopteryx drew a blank.

“And they’re scientists,” she said.

Will the Chicago Archaeopteryx match Sue in its appeal? Probably not, Siggers said, but the Field is giving the specimen the full superstar treatment.

The actual fossil, to be clear, not a reproduction.

“What’s the point of bragging that you have this thing if the real thing is locked away somewhere and you’re just looking at a plastic cast that any museum could have?” O’Connor asked.

Archaeopteryx will be on temporary exhibit through early June and then head backstage while its permanent exhibit is being built. Among the bells and whistles in the works: interactive components, models, animations and a hologram. Other techniques include the use of UV light to highlight fossil details.

“I think there are opportunities to show how magnificent the specimen is,” Lumbsch said. “I mean, the crown jewel is also not huge. I would actually hope it can contribute to the pride of citizens of Chicago, having this species that’s only shown in replica at other museums.”

There is, to be sure, one person who will be drawn to the exhibit like a moth to a flame.

Between her furious dash to finish writing her research papers, and planning sessions with the exhibits and marketing teams, there hasn’t been much time for O’Connor to simply revel in the glory of the Chicago Archaeopteryx.

Except this one day.

The entire museum was empty, everyone told to take a staff wellness day. O’Connor requested an exemption. At the time Shinya and Van Beek were in the final stages of prep work, so here was a chance for O’Connor to have the specimen to herself.

“It’s just me and the Archaeopteryx, and I got emotional,” O’Connor recalled. “I almost cried.”

“I spent about three or four hours just looking at the specimen, taking notes, working on the line drawing, and really finally having that moment to be like, ‘Oh my goodness, look at this beautiful specimen,” O’Connor said. “And how lucky am I that I get to work on this incredible, incredible fossil?’”

Once the unveiling has passed, O’Connor is looking forward to more down time, and the chance to reconnect with her old bird.

“You’ll probably find me hanging around the exhibit,” she said, “just gazing at it adoringly.”

Read More:

- Birds Are Dinosaurs: How a Family Tree That Spans T. Rex to Pigeons Informs Our Understanding of Life on Earth

- Where in the World is Archaeopteryx?

- Meet Jingmai O’Connor, the Punk Rock Paleontologist Who Leads the Field Museum’s Archaeopteryx Team

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]