The Woodlawn home of Emmett Till received a preliminary landmark designation last month from the City of Chicago.

It’s one of the latest chapters in the battle to preserve Chicago’s historic buildings, which officially began fifty years ago this month.

Geoffrey Baer traces the half-century story that cost at least one preservationist his life, in this week’s Ask Geoffrey.

When did Chicago start landmarking buildings, and why? Does it truly save them from being torn down?

— Chicago Tonight team

Landmark status in Chicago usually protects from demolition the parts of a building visible from the public way, like the façade. Today we take it for granted that many buildings with historic and aesthetic value are preserved as landmarks, but it’s a relatively new practice here.

In fact, the first official Chicago landmarks were designated just 50 years ago this month: the Glessner and Clarke Houses in what we now call the South Loop.

The idea of landmarking in Chicago got off of the ground several years earlier. In the late 1950s, several groups started worrying about the number of pioneering skyscrapers of the so-called “Chicago School” that were being torn down and started pushing the city to do something about it.

In 1960, the city granted more than 30 Chicago buildings “honorary” landmark status. But that didn’t come with any legal authority to keep buildings standing.

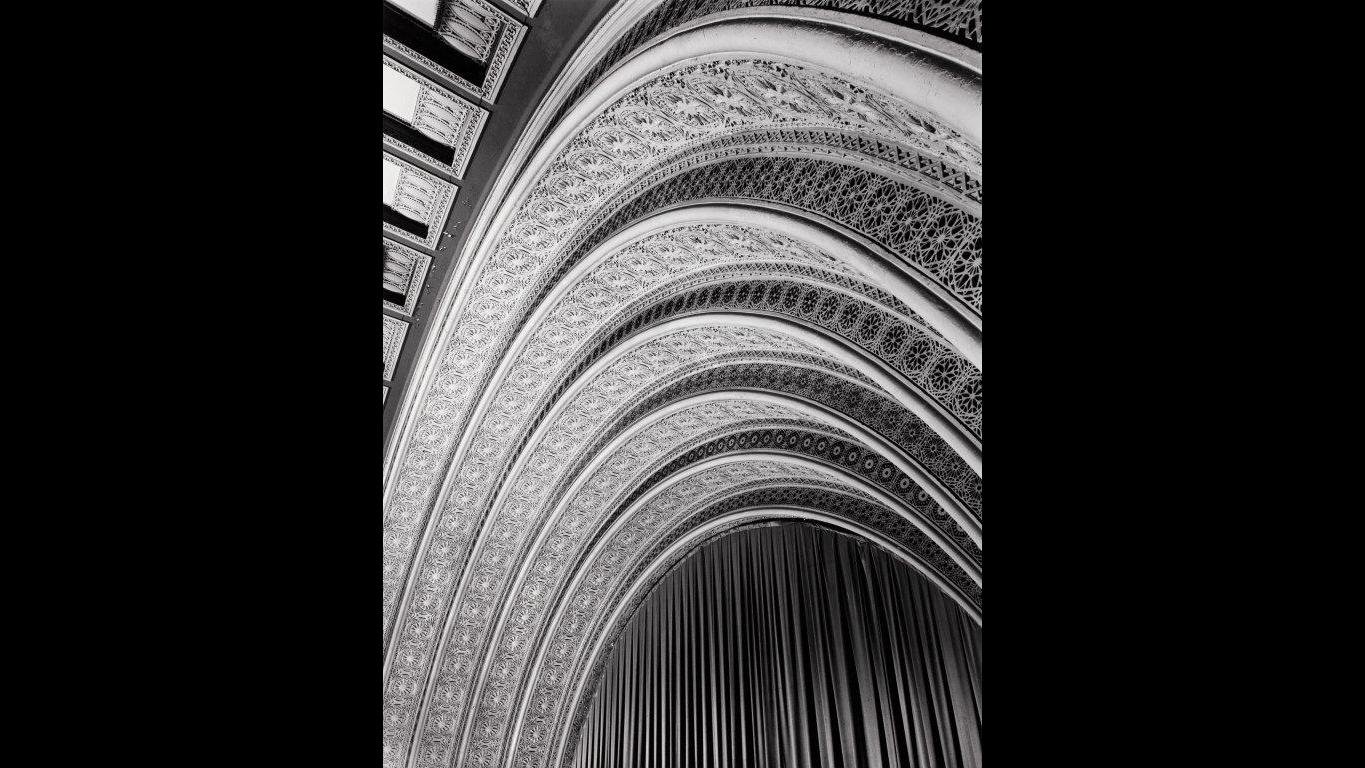

This was put to the test later that year, in one of Chicago’s first huge preservation fights to save the Garrick Theater in the Loop – which had received that honorary status.

The building, with its stunning auditorium and “Chicago School” exterior, was designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler.

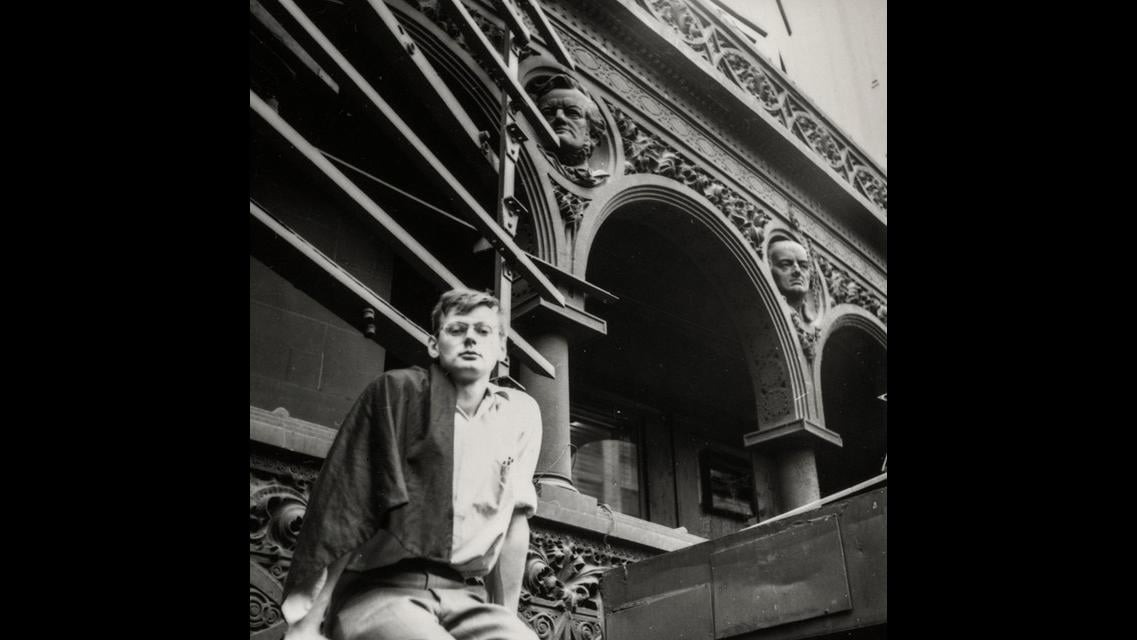

The battle to save the theater ultimately failed, but out of it emerged an unlikely hero: a photographer named Richard Nickel. For decades he fought to save Chicago’s architectural treasures, especially the work of Louis Sullivan. His passion would ultimately cost him his life.

Nickel was killed in 1972 when part of Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange collapsed on top of him during demolition while he was inside scavenging ornament.

Four years before Nickel’s tragic death, in 1968, the city had in fact passed a new landmark ordinance that actually had the legal power to protect buildings.

And Glessner and Clarke were the first they selected.

Completed in 1887, Glessner House was designed by architect Henry Hobson Richardson for the family of farm machinery magnate John Glessner.

The building was a radical design compared to the neighboring Victorian-style mansions that lined Prairie Avenue, Chicago’s swankiest street in those days.

Its Romanesque fortress-like edifice opens up to a large inner courtyard that brings in light while maintaining privacy.

The Henry B. Clarke House stands next to Glessner. This Greek Revival frontier house built in 1836 is the second-oldest home still standing in Chicago.

In the decades since, there’s been a constant tension between development interests and preservationists.

In 2014, Bertrand Goldberg’s brutalist, Prentice Women’s Hospital with its wacky oval windows was torn down after a lengthy preservation fight.

Then there’s the Thompson Center in the Loop, which the state of Illinois wants to sell and preservationists want to save.

Landmarks are today still officially designated by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks and ultimately the City Council. That same body can un-designate a property to tear it down, but that’s quite rare.

Preservation battles are often portrayed as the big evil corporation versus the community. But it’s often far more nuanced and complicated.

A recent example is the city’s proposed Pilsen Landmark District, which would preserve hundreds of baroque and Italianate buildings in this majority Mexican American community, originally built by Bohemian immigrants in the 19th century.

But many current homeowners see the landmark proposal as a potential catalyst for gentrification – and say that increased costs with maintaining landmarked properties could force them to move.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.