Demonstrators march in Chicago on Wednesday, June 24, 2020 to show their support for removing police officers from schools. (WTTW News)

Demonstrators march in Chicago on Wednesday, June 24, 2020 to show their support for removing police officers from schools. (WTTW News)

Chicago officials failed to act after the city’s watchdog found significant problems with the program that allows Chicago police officers to patrol schools, and used a federal judge’s order requiring reforms to delay any changes, the city’s watchdog told aldermen.

City officials took no action after a 2018 audit by Inspector General Joseph Ferguson found the program was so poorly run that it increased the “probability that students are unnecessarily becoming involved in the criminal justice system.”

Instead, city officials decided to follow the deadlines set by a federal judge to implement a series of reforms, including one requiring the Chicago Police Department to use “screening criteria” to ensure that qualified officers are assigned to schools and given specialized training, Ferguson said.

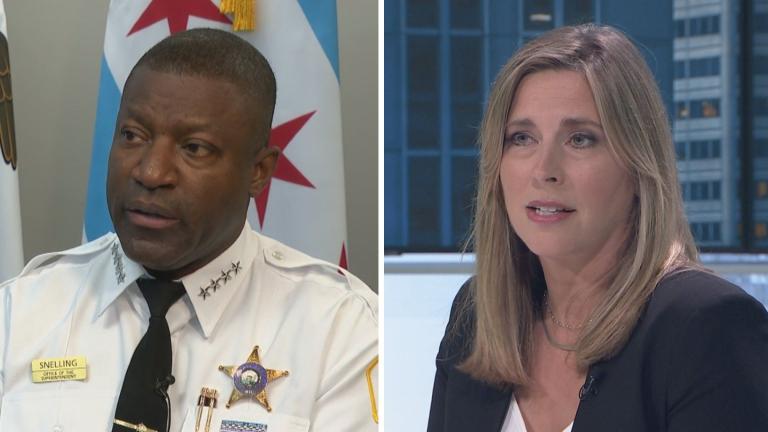

However, a report from Independent Monitor Maggie Hickey, charged with making sure the reforms are implemented, found that efforts to reform the city’s school resource officer program were incomplete and missed several deadlines.

“CPD’s failure to act more expeditiously left students, teachers, parents and community stakeholders without the protections and assurances of an appropriate school safety program for another entire school year,” Ferguson said. “Essentially, CPD and the city used the consent decree as a shield to slow readily achievable reform that they acknowledged was needed.”

Chicago Police Department Deputy Supt. Barbara West, who leads the CPD’s reform efforts, said significant policy changes have been made this year to the school police program, even as efforts were delayed by the coronavirus pandemic.

Ferguson’s audit found that the roles or responsibilities for school resource officers were not codified in writing, there were no guidelines for officials to use when selecting officers to patrol schools and no training was required for the officers.

A follow-up audit, issued by Ferguson in June 2019, found that Chicago police officials ignored all but one of his recommendations to ensure that the roster of officers assigned to schools is regularly updated.

As part of a five-hour hearing during a joint session of the City Council’s Public Safety and Education committees on Thursday, Ferguson blasted aldermen for failing to examine the problems he detailed in his audit as required by city ordinance.

Had a hearing been held sooner, Ferguson said the program could have been improved sooner while reducing public anger and frustration about the program now at the center of the effort to reduce funding for the Chicago Police Department in the wake of the protests of George Floyd’s death last month in Minneapolis police custody.

Of the approximately 2,000 people who were arrested inside or near Chicago Public Schools since January 2017, 78% are Black and nearly 18% are Latino, Ferguson said. In addition, approximately 51% of those stopped by police officers inside or near schools are Black, and approximately 31% are Latino, according to data Ferguson shared with aldermen.

CPS’ students are 36% Black and 47% Hispanic, according to district data.

Ferguson said the data included arrests and stops outside of school hours, but nevertheless adds fuel to the perception that Black and Latino students are more heavily policed by officers than white or Asian students.

Several aldermen who favor removing officers from Chicago’s schools repeatedly asked schools and police officials for data about the program, only to be told that it was not available Thursday but would be provided later.

Ald. Rossana Rodriguez Sanchez (33rd Ward) asked officials for the number of students at schools with officers who are arrested and enter the criminal justice system as well as that data for students at schools without school resource officers.

Rodriguez Sanchez vowed to push for those answers.

Other aldermen asked about the number of complaints filed against school resource officers and whether any have been removed for misconduct, but were also told that information was not available.

Chicago Public Schools spends $33 million annually to place city police on campuses. The school district also employs security guards. The Chicago Board of Education will consider renewing that contract in August.

An ordinance to end that contract and remove school resource officers from schools failed to advance June 17, and is mired in legislative limbo. Ald. Chris Taliaferro (29th Ward), the chair of the Public Safety Committee, said Thursday he would schedule a hearing and vote on that measure.

However, that effort is unlikely to be successful without the support of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who does not support removing police from Chicago schools.

All of the local school councils voted in September to keep police officers in their schools, and CPS CEO Janice Jackson supports the program.

There are currently 144 school resource officers assigned to CPS schools as well as 48 mobile school officers and 22 staff sergeants, according to the Chicago Board of Education.

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]