2020 is the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment, which secured women’s right to vote. Next Tuesday, “The Vote,” a major two-part PBS documentary about the long fight for women’s suffrage premieres on WTTW, which we thought gave us a great opportunity to talk about a related conflict between two famous local titans of social justice – Ida B. Wells of Chicago and Frances Willard of Evanston. At its center was the tension between crusaders for women’s voting rights and crusaders for Black citizenship and voting rights that emerged during the Reconstruction period after the Civil War.

Prior to the end of the war, abolition and women’s rights groups were tightly aligned. In fact, the first women’s rights convention, the 1848 Seneca Falls meeting, was organized by two abolitionists, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Many of these groups were interracial and included men and women as members, though while most women’s rights advocates supported abolition, the reverse wasn’t necessarily true.

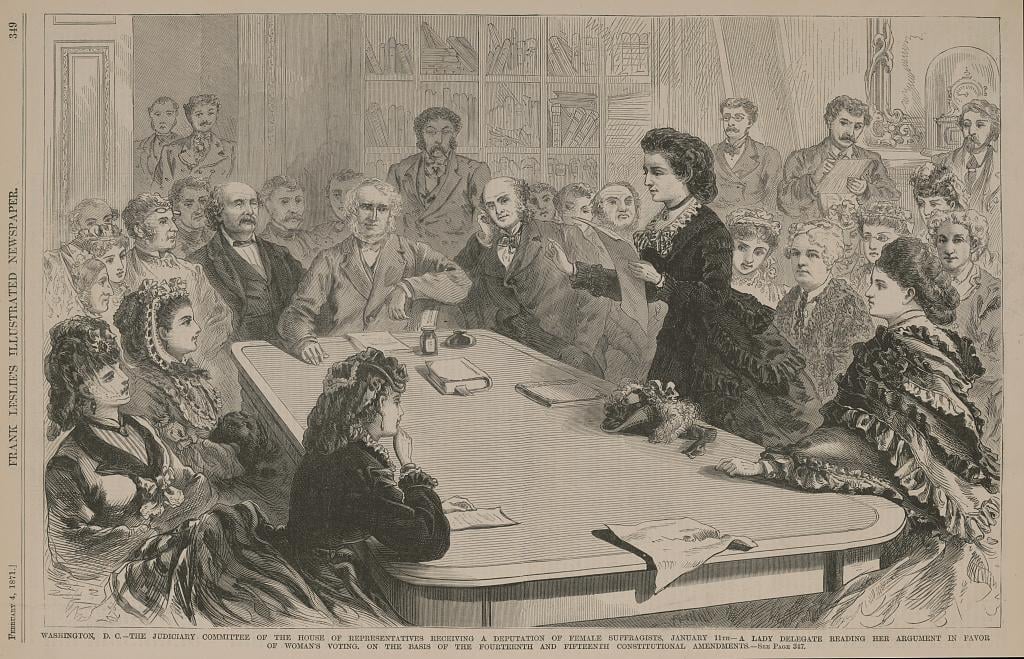

Once the 14th and 15th amendments were proposed to secure citizenship and voting rights to formerly enslaved men, the fight for their enfranchisement took precedence. Even Frederick Douglass, a self-described “women’s rights man”, argued that women’s suffrage would have to wait until the right for Black men to vote was obtained.

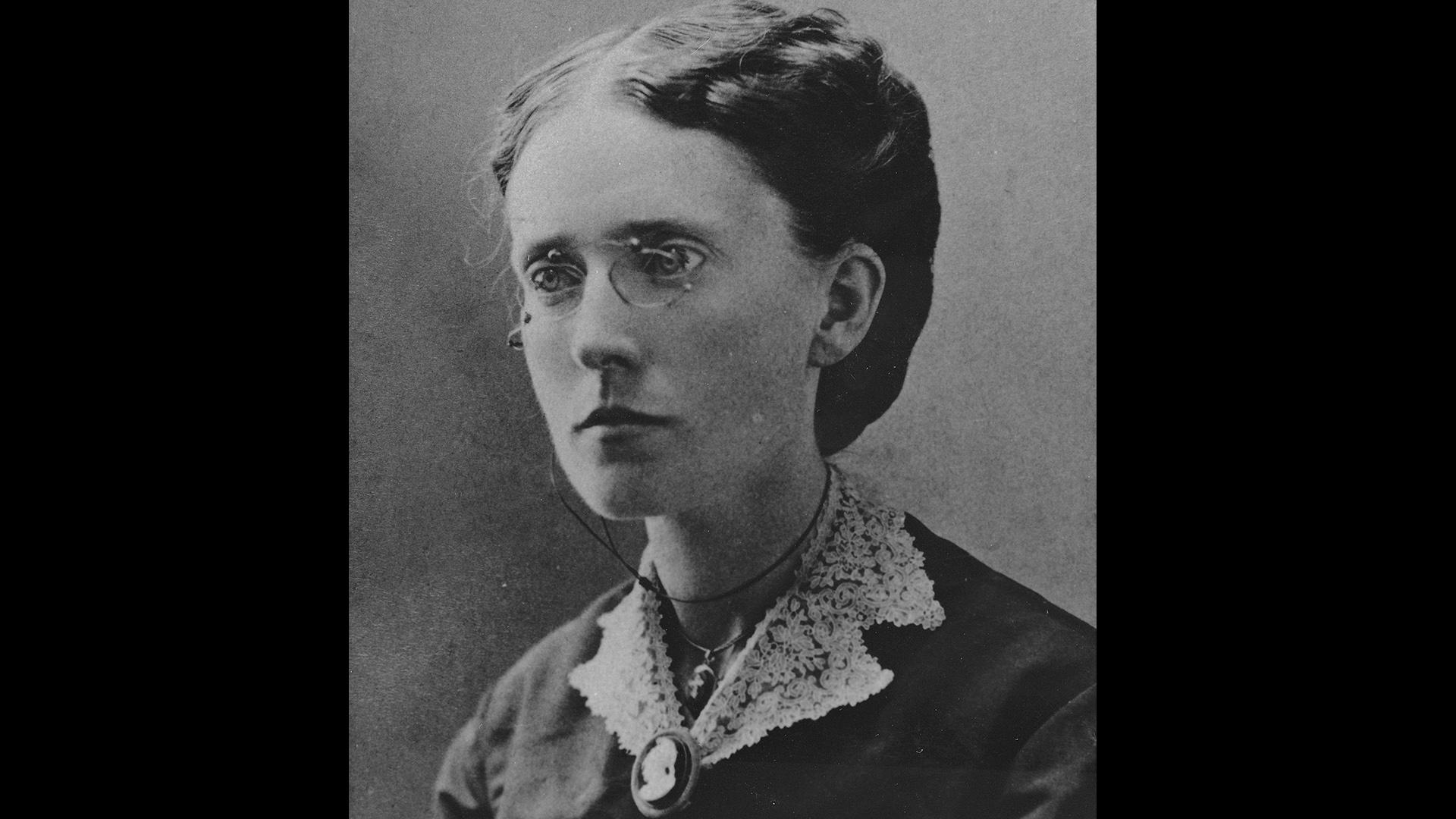

Frances Willard was among those agitating to put women’s suffrage first.

(Courtesy of the Frances Willard House and Archives)

(Courtesy of the Frances Willard House and Archives)

Her name will ring a bell for Evanstonians in particular. She was the former Northwestern University Dean of Women who, in 1872, embarked on a new career promoting the temperance movement, a social effort led by women to outlaw the manufacture and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

In 1874, Willard was elected the first corresponding secretary of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and she began traveling the country to build support for the WCTU’s cause. She claimed to have visited more than 1,000 American cities and towns to spread the temperance gospel.

Five years later, she was elected president of the organization. Under her leadership, the WCTU grew to be the largest organization of women in the nineteenth century.

While WCTU president, she urged the organization to work for social reform beyond temperance, including women’s suffrage. She felt that if women got to vote, they would be the key to passing a constitutional amendment prohibiting alcohol.

By the time she first met Ida B. Wells in 1892, Willard was one of the most famous and powerful women in the country.

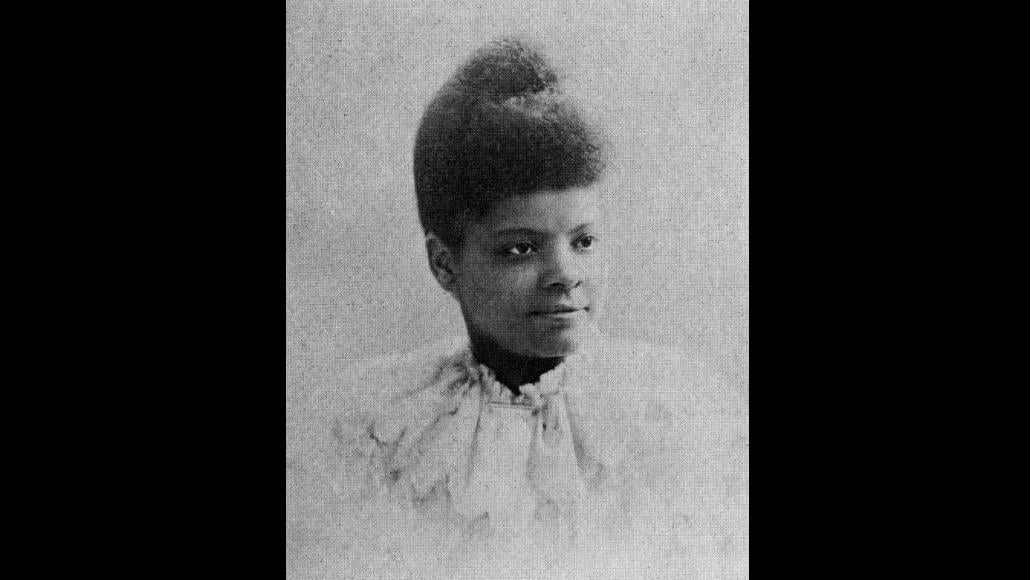

Ida B. Wells is a name familiar to Chicagoans. She’s probably best-known for her work as a journalist exposing the horrors of lynching, for which she was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize this past May.

Born into slavery in Mississippi in 1862, Wells went on to become a formidable civil rights leader and was a founding member of the NAACP. But when she met Frances Willard, Wells was just getting started.

In 1892, after one of her close friends in Memphis was murdered by a white mob, Wells launched an anti-lynching crusade and publicly criticized Willard and other white reformers for not supporting her anti-violence movement in essays she wrote for the Chicago Inter Ocean.

Wells took particular issue with an 1890 interview Willard gave to the New York newspaper The Voice in which she made statements that vilified Black men and implied they were dangers to white women – the very sentiments lynchers used to justify their murders of Black men.

Among Willard’s remarks was “The colored race multiplies like the locusts of Egypt. The grog shop is its centre of power. The safety of women, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment.”

In Wells’ words, Willard had “unhesitatingly slandered the entire Negro race in order to gain favor with those who are hanging, shooting, and burning Negroes alive.”

(Courtesy of the Frances Willard House and Archives)

(Courtesy of the Frances Willard House and Archives)

This offense was compounded because up to that point, Willard and the WCTU had been considered friends to the Black community since northern WCTU chapters were integrated.

In 1894, Wells was invited to speak about her anti-lynching crusade in in Great Britain before British temperance advocates. Among the organizers was the head of the British movement, Lady Henry Somerset. At the time, Frances Willard was a guest of Lady Somerset and also an invited speaker.

Willard and Wells met for the first time at a reception the night before Wells’ speech, and in a later recounting of their meeting, Wells gave the impression that she was able to change Willard’s mind about lynching.

But that conversation put Wells in a tough position, as she had arranged to have Willard’s New York Voice interview republished in a London newspaper the following day.

When Willard’s words hit the press, they kicked off a war of words between the two women and their supporters in British and American newspapers.

Willard reacted defensively, calling Wells’ characterization of her remarks “absurd” “impulsive” and “untrue” and suggested Wells would lose support for her cause for her imprudence.

Wells hit back immediately, saying “Miss Willard is no better or worse than the great bulk of white Americans on the Negro question. They are all afraid to speak out.”

The women traded barbs in the press for months, but ultimately, the pressure was on Willard to take a public stand against lynching.

In the wake of the dispute, the WCTU indeed put forward multiple anti-lynching positions, with a resolution finally passing in 1895.

Sadly, Willard was already in poor health by then and she died in 1898 at just 58 years old with her legacy clouded by this clash.

Wells continued to fight racism and injustice for another 30-plus years.

A 1913 incident is featured in “The Vote.” Suffragist leader Alice Paul organized a women’s march in Washington, D.C. and invited all women to join the march. But once word got to D.C. that Black women were also planning to attend, many white suffragists made it clear to Paul that they would not participate in an integrated march.

The march’s organizers gave into their demands and segregated the march, but Wells was undeterred.

Halfway through the march, she emerged from a chaotic scrum of drunken male spectators to triumphantly take her place at the front with the Illinois delegation.

All of this information and more is documented in an incredible online exhibit called “Truth-Telling” from the Frances Willard House Museum and Archives in collaboration with and scholars from Northwestern University and Loyola University Chicago, and we highly recommend a visit.

One last thing – we mentioned earlier that Willard’s name is well-known in Evanston. That’s because there are a lot of things named after her there, among them a grade school.

But one Evanston business that gets associated with her is actually a craft alcohol distillery named FEW Spirits. Some folks say that the letters FEW stand for Frances Elizabeth Willard, a cheeky reference to her temperance stance.

We spoke to the company’s founder and master distiller, who assures us that the name merely refers to the rarity and specialness of its products, and that they would never name a liquor brand after an elementary school.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.