Longtime Chicago Ald. Roman Pucinski once said, “There’s nothing as crucial to an alderman as garbage.” So how did garbage cans become a source and symbol of political power in this city?

Geoffrey Baer offers some trashy history in this installment of Ask Geoffrey.

When I was walking home today, I saw this concrete box in an alley in West Edgewater. Was this product the predecessor to our modern free-standing home garbage cans?

— Jean SmilingCoyote, West Ridge

(Courtesy of Jean SmilingCoyote)

(Courtesy of Jean SmilingCoyote)

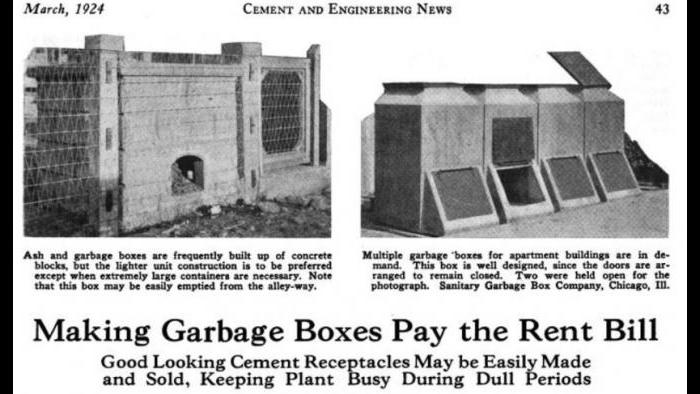

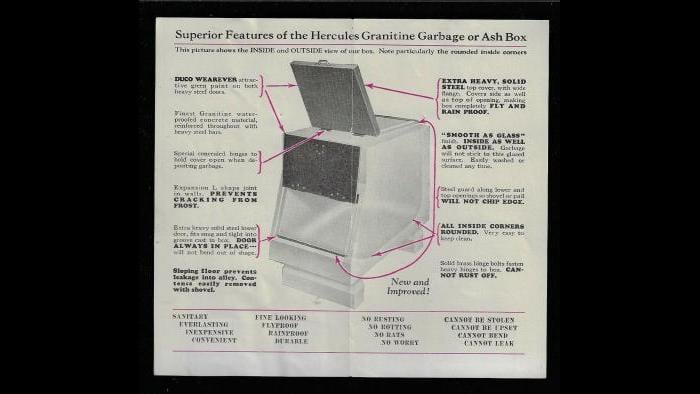

Above is Jean’s photo of the box she spotted. She’s right that this is basically an old trash receptacle, also used as an incinerator, made of concrete and metal. A handful of local garbage box makers manufactured these from the 1920s through the 1940s – this one was made by the Sanitary Garbage Box Co.

Here’s how they worked: residents would throw their trash in the top opening – and would often burn it in there — and sanitation workers would shovel out the trash or ashes through a second opening near the bottom on the alley side.

Beginning in the 1950s, the city phased them out because they were small and difficult to empty without leaving a trail of debris, making them a favorite dining spot for rats. But since it took a demolition crew with sledgehammers to dismantle the boxes, some of them were never torn down, and you can still spot them here and there throughout the city.

As the concrete boxes were phased out, the city required residents to supply their own covered metal garbage cans to replace them, and many citizens balked at the expense.

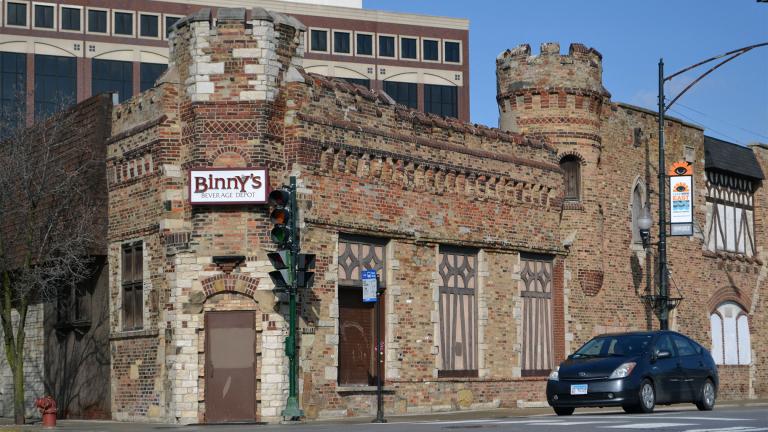

Trash collection was handled separately in each ward, and the alderman and other ward bosses often saw the service as a way to win favor and votes from constituents. So in some wards, they began providing 55-gallon steel drums free of charge with the name of the responsible politician stenciled on the side.

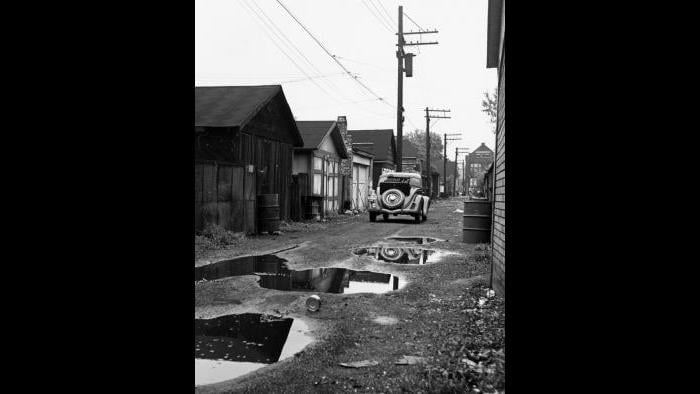

Greg Basil, former superintendent of streets and sanitation for the 44th Ward, says he fondly remembers “Bernie cans” stenciled with the line “compliments of Alderman Bernie Hansen.” Other barrels carried the name of 43rd Ward Superintendent Pete Schivarelli and 47th Ward Committeeman Ed Kelly, who handed out turquoise barrels emblazoned with the words “Kelly Cans” as seen in this 1981 photo of an alley in the Ravenswood neighborhood.

(C. William Brubaker Collection)

(C. William Brubaker Collection)

The plastic carts now lining the city’s residential alleys began appearing during Mayor Harold Washington’s administration in 1985. They saved money because just one sanitation worker is needed to attach the cart to a motorized arm that dumps trash into the truck. 47th Ward Ald. Gene Schulter was an early adopter because the carts replaced the “Kelly Cans” of his rival Ed Kelly.

But how the trash gets collected is only half the story – once it’s picked up, then where does it go? Like many other big cities, historically Chicago has employed two strategies for trash: burning it or dumping it.

As Chicago grew from a town to a city, so did the volume of trash it had to manage – and over the years, the composition of trash has changed as well, from mostly biodegradable materials like paper and food waste to today’s additions of plastics, household chemicals and electronic waste.

(Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

(Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum)

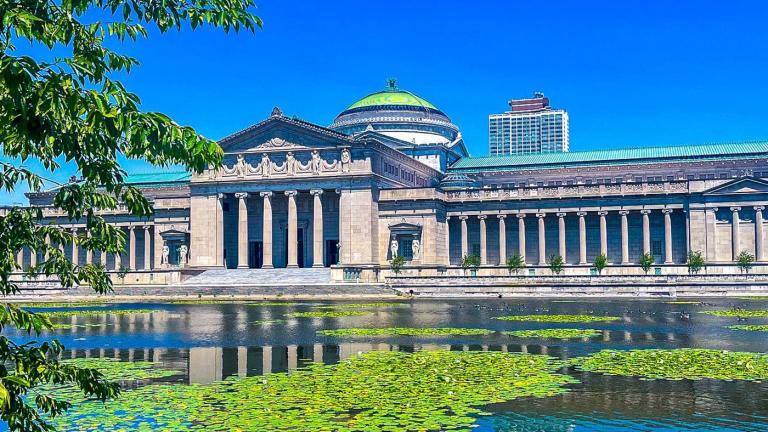

In 1849 the city appointed its first garbagemen, then called scavengers, to collect waste and dump it at the edge of the city. It sounds gross, but these early dumps actually raised the level of the land, which allowed the marshy city to be built upon. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, many Chicago buildings and streets stand on as much as 12 feet of 19th century trash.

Later, the stone quarries and clay pits once used by brickmakers were re-purposed as garbage dumps that were eventually built over. In other areas, decades of dumping thousands of tons of trash daily into landfills literally changed Chicago’s topography, creating mountains up to 17 stories high in places.

But there was only so much space for landfills, and for obvious reasons, no one wanted new landfills in their neighborhoods. Eventually all the dumps within the city limits filled up and many were built over, and Chicago gave citywide incineration a try.

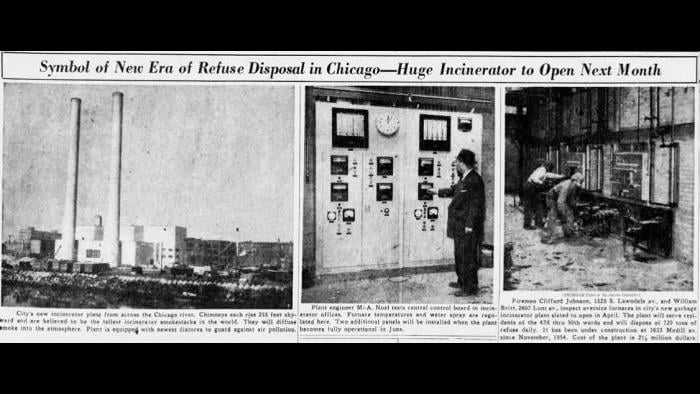

Though municipal trash incineration programs were tried out as early as the 1890s, early efforts simply couldn’t keep up with the growing city’s volume of trash. Beginning in the mid-1950s the city adopted air pollution control ordinances that prohibited households from burning trash themselves. Instead, garbage collectors would bring the trash to giant incinerators at different sites around the city, which were theoretically cleaner burning than open-air burning. Schools, hospitals and other large buildings typically had their own incinerators as well.

But by the 1980s, the appearance of more plastics, consumer electronics, and toxic chemicals in the trash created air pollution worries that ended incineration. The last municipal incinerator closed in 1996.

With incineration permanently off the table, that left a return to landfills as our only solution. Today, there are no active landfills within city limits, and Chicago’s non-recyclable trash ends up about 100 miles away in one of four landfills, two in Illinois and two in Indiana. But that waste doesn’t entirely go to waste — the gas created as trash decomposes is captured and sent to a gas-to-energy plant, which then sells it to utility companies.

Pretty much everyone can agree that the best strategy for tackling our trash problem is simply reducing the amount we produce and recycling as much as we can. In the last 30 years, Chicago has made a few attempts at comprehensive recycling programs. The Daley administration made its first attempt at a recycling program with the “Blue Bag” system in 1990, but it was a flop. It was replaced beginning in 2007 with the blue cart program we have today, in which recyclables can be disposed of in a blue cart.

(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

Even with this program, Chicago has one of the worst rates for recycling in the country – according to a report by the Better Government Association, less than 9% of Chicago’s residential waste is actually recycled.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.