History buffs are big fans of historical markers, those often-overlooked plaques that tell the tales of site-specific events from years past.

Our own resident history buff Geoffrey Baer tells us about some historical markers around Chicago that don’t quite hit the mark.

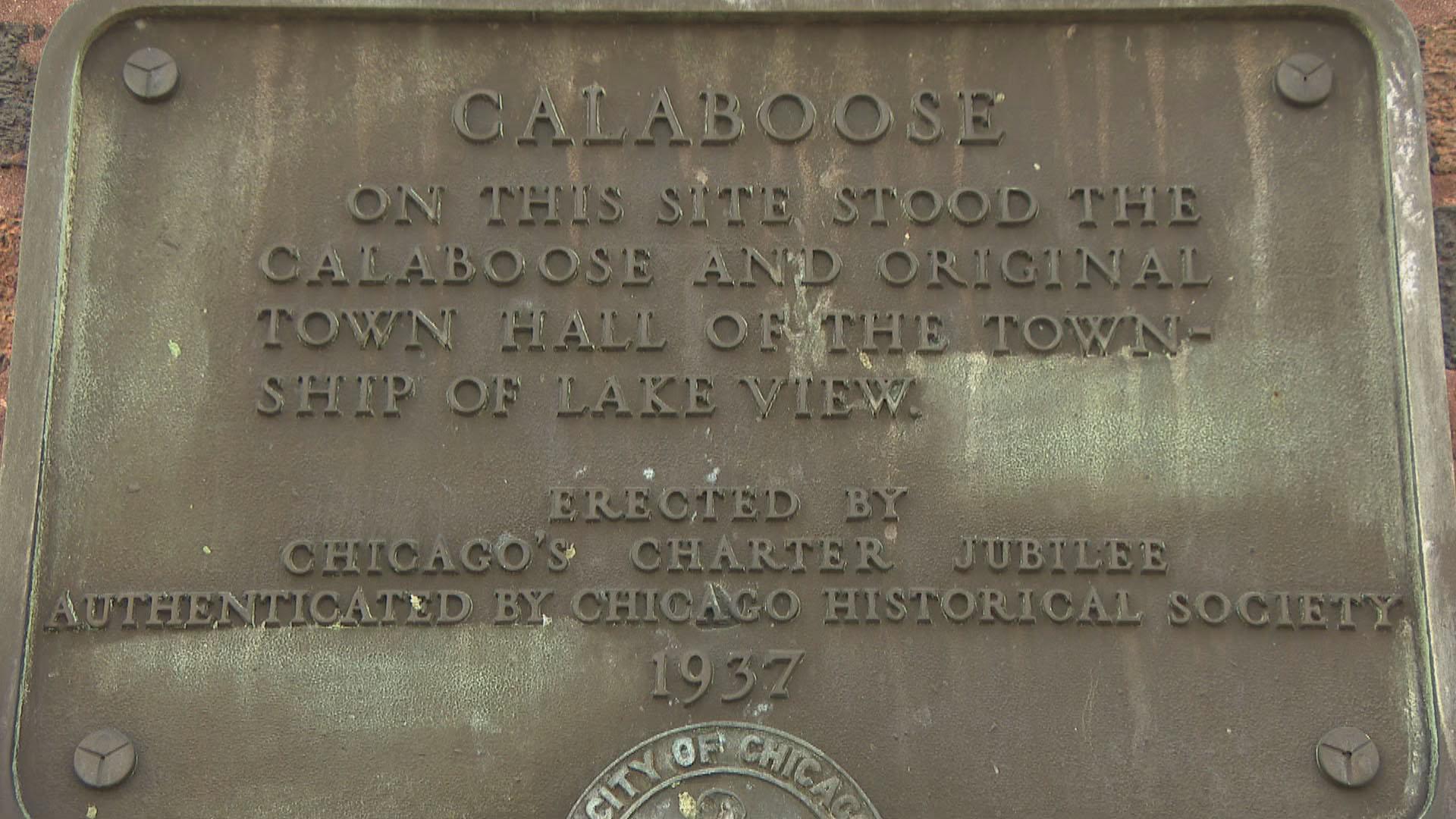

A brass plaque on the side of an apartment building at Byron and Clark says something about a Calaboose. What is it talking about?

— Larry Rolnick, Lakeview

A confession: before we could answer this question, we had to look up what a “calaboose” is! Turns out it is another word for jail (you have to appreciate how many slangy words there are for jail – big house, clink, pokey, hoosegow. Fun stuff!) “Calaboose” derives from the Spanish word for “dungeon” and fell out of use around the 1920s.

Back to the plaque: it’s a 1937 Chicago Charter Jubilee Marker, one of about 70 historical markers that were installed all over the city to celebrate Chicago’s 100th birthday. All but around a dozen of them are gone now.

On the plaque in question, this calaboose refers to the jail of the Town of Lake View, which began life as farm country turned township. The town was annexed to Chicago in 1889.

Here’s the trouble: according to the town’s records, the original Lake View calaboose was in the same building as the town hall, which was at the northwest corner of Addison and Halsted – nearly a mile away from the Byron and Clark marker. It’s certainly possible that another jail existed where the marker stands, but despite the inscription that each marker was “Authenticated by the Chicago Historical Society,” Charter Jubilee markers don’t have a great reputation for accuracy. (It should go without saying that we have nothing but respect for the rigorous scholarship of the CHS’ successors at the Chicago History Museum.)

Similarly, there’s another marker in the Sauganash neighborhood on the Northwest Side that reads “Old Treaty Elm.” The tree stood there until 1933 and the plaque reads that it “marked the Northern Boundary of the Fort Dearborn Reservation, the trail to Lake Geneva, the center of Billy Caldwell’s (Chief Sauganash) Reservation, and the site of the Indian Treaty of 1835.”

And you guessed it: nearly none of that is true. No treaty was signed under it – in fact, there was no Indian Treaty of 1835 at all. The Treaty of Chicago took place at Fort Dearborn near the mouth of the Chicago River in 1833.

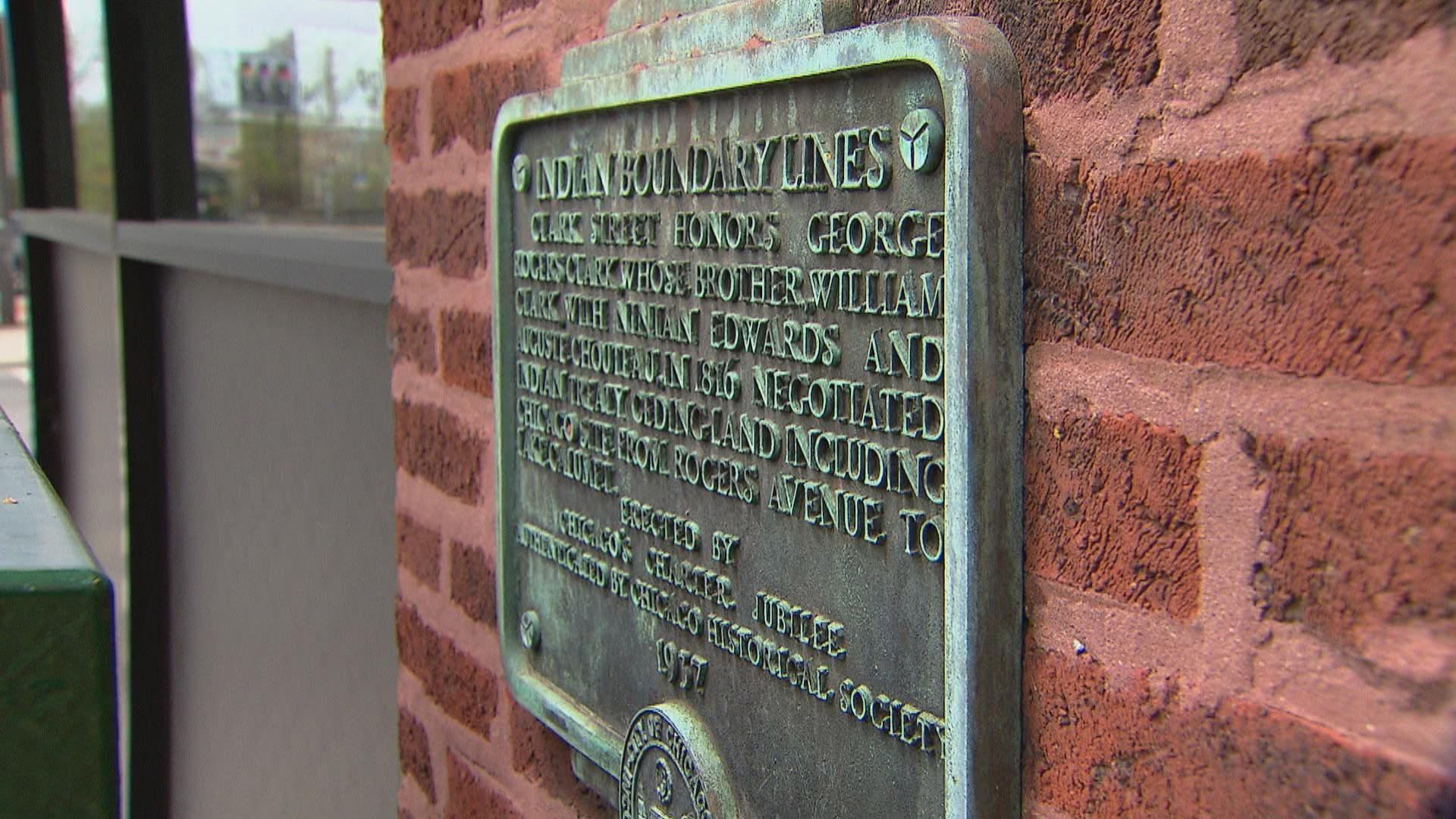

But it does get one thing right: the property upon which it stands belonged to a Native American named Billy Caldwell or Sauganash. The U.S. government had given him the land in exchange for helping negotiate treaties with non-native settlers. He had to live way out there because of the Indian Boundary Line, which is marked by another Charter Jubilee plaque at Rogers and Clark Streets. This line was established in 1816 to keep Native Americans far from Chicago. If you happen to be in the area, you’ll have to look sharp for it – it’s mostly hidden by a traffic control box. Guess not everyone’s into Chicago history.

The 78 plaques planned for installation by the Chicago Charter Jubilee committee were just one part of a monthslong centenary celebration of Chicago’s 1837 city charter. (They took some pains to point out that the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair celebrated the centenary of Chicago’s 1833 town charter, in case people were wondering why they were celebrating Chicago’s hundredth birthday again just four years later.)

The festivities opened with a parade on March 4, 1937, through the Loop led by the Jubilee queen – Miss Lorraine Ingalls of Garfield Park – who was costumed as the “I Will” figure created in 1891 to represent the spirit of Chicago. The same day, a play depicting Chicago’s pioneer days was presented in Chicago Stadium.

For those of us who remember Chicago’s old yellow-and-black street signs, those were also part of the Charter celebration. Mayor Edward Kelly put up the first one at State and Madison Streets as part of the Charter Day celebration.

And that was just the beginning. Through the following months, there were horse shows, a folk dances, themed luncheons, you name it. One event, a “Farm Olympiad,” brought in young women to compete in cow milking, husband calling and a rolling-pin toss (the dummy target, affectionately named Joe Blow, only suffered one “glancing blow” according to the Chicago Tribune account). The following day, young men competed in post driving, hog calling and horseshoe pitching.

The celebration even hit the road – a covered wagon traveled to cities across the country to lure tourists to visit Chicago.

The commemoration culminated in October with the opening of the Centennial Bridge at Lake Shore Drive across the Chicago River, which was dedicated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. At the ceremony, FDR barely mentioned the bridge at all in his speech, and delivered what became known as his “quarantine” speech, equating the tyrannical Axis governments to contagious viruses.

Anyway, back to the plaques. Despite their wobbly accuracy, they do give us an idea of what Chicago was like in both the days they’re remembering and the attitudes of the day in 1937 they were erected.

For instance, the marker for the Kinzie Mansion that, until recently, was on a pylon near Michigan Avenue and the river, read: “Here was born, in 1805, the city’s first white child, Ellen Marion Kinzie.” This all but ignored that the home’s first owner was a person of color, in fact Chicago’s first permanent resident Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable. And the date was wrong too – Ellen Kinzie was actually born in 1804.

Another lost plaque nearby that identified an early home of Billy Caldwell described him as a “half-breed.”

But many more of the plaques were neither inaccurate nor offensive. Among them were plaques commemorating homes of historic figures, sites of historic events and many “firsts” like the first theater, the first land office and the first places of worship.

Another “first” a plaque used to commemorate was the site of the first drawbridge across the Chicago River at Dearborn Street. It was erected in 1834 with leaves of timber that were supported by chains and cranked up by hand – and it frequently got stuck. The city council ordered it torn down, but the citizenry, fearing the city would stay the bridge’s execution, hacked it to pieces with axes under the cover of night.

You can still visit a plaque marking the first home with a telephone in the Lakeview neighborhood at 1464 N. Leland. It belonged to John N. Hill, and the only two other phones in town he could call were in the town hall and a local bar. To be fair, who else would you need to call?

Other Jubilee plaques marked wooden plank roads on the West and Southwest sides, which were the state of the art in highway paving in frontier days. There were plaques in Albany Park and Jackson Park that marked an 18th century French mission and visiting missionaries, reminding us that the very earliest visitors here were French Canadian. Camp Douglas, a Civil War POW where thousands of Confederate prisoners died in miserable conditions was marked by a plaque at 31st and Cottage Grove. There was even a plaque near Beverly marking a safe house on the Underground Railroad.

And another lost plaque marked the famous Loop cowpath. A passageway through what is now a hotel at 100 W. Monroe that was left open when the building was constructed in 1928 supposedly because in the 1840s, an enterprising farmer named William Jones purchased a lot at Clark and Monroe street and set up his barn in one corner. Later he sold off strips of the remaining land, but reserved in the deed a 10-foot-wide strip for himself to lead his cows to pasture. The 1928 building standing there circumvented the stipulation in the deed to keep the path open by building a passageway through it.

The path gained some notoriety in 1932, when a cow named Northwood Susan the Sixth and her calf Buttercup were paraded through the passageway to mark the opening of the International Livestock Exposition.

Mayor Kelly himself placed the jubilee plaque there in 1937, but according to a Tribune item, an attorney for the building said that though there was an easement on the property dating back to 1846, there was no hard evidence proving that it was, in fact, a cowpath. Just one more historical casualty of the Jubilee plaques.

If you’ve spotted one of the Jubilee plaques around Chicago (whether it’s in a spot it was installed or … elsewhere, wink wink), send us a photo! We’d love to see it.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Did you know that you can dig through our Ask Geoffrey archives? Revisit your favorite episodes, discover new secrets about the city’s past, and ask Geoffrey your own questions for possible exploration in upcoming episodes. Find it all right here.

Do you have a question for Geoffrey? Ask him.