The City of Chicago has given up on treating parkway ash trees, so neighbors are taking it upon themselves. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

The City of Chicago has given up on treating parkway ash trees, so neighbors are taking it upon themselves. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Chicago has given up on its ash trees.

The Department of Streets and Sanitation is no longer inoculating parkway ash trees against the emerald ash borer, the mass-murdering beetle that’s laid waste to tens of millions of ash trees across 35 states. Instead, the city will focus on removing dead and infected ash and replacing them with other species, according to Marjani Williams, department spokeswoman.

Lorin Liberson, for one, said she was stunned to learn of the city’s decision to stop treating its ash and intends to not only save the one in her parkway but her neighbors’ trees, too.

“We have probably the largest ash tree in the neighborhood, it’s a monster,” said Liberson, who lives in Ravenswood Manor on the North Side. “This tree is the house.”

The Manor’s tree-lined streets are one of the area’s defining characteristics — “It’s part of why we chose this neighborhood,” Liberson said — and losing the nearly 100 remaining ash trees would dramatically alter not just its look, but its feel.

Her entire house is shaded in the summer by just that one ash, Liberson said. “We can have our windows open and not have the air conditioning on.”

So she and neighbor Debbie Robinett put together a rescue plan that boils down to Manor residents chipping in to treat their parkway ash trees themselves.

The women conducted an ash tree census of the Manor earlier this year, tallying 99, a dozen or so of which probably are too far gone to save. For the rest, they negotiated with an arborist for a volume treatment price of $150 per tree, and then asked for donations, placing notices in the community’s newsletter, on the neighborhood’s Facebook page, and leaving letters in the mailboxes of every ash tree owner.

“We almost have all the money. The neighborhood is very generous,” Liberson said.

Treatment will need to be repeated every three years, though Liberson said she’s hopeful that at some point the borer may have moved on, or new, cheaper treatments will have been discovered.

“We’re not scientists, we don’t know. We’re going to take it one inoculation at a time,” said Liberson. “But I really believe there’s an end game.”

Telltale tags mark parkway ash trees that the city was treating for emerald ash borer. The Department of Streets and Sanitation will no longer inoculate parkway ash. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Telltale tags mark parkway ash trees that the city was treating for emerald ash borer. The Department of Streets and Sanitation will no longer inoculate parkway ash. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

If the Manor succeeds in saving its trees, it will form an ash canopy corridor with neighboring Horner Park, where the tree-obsessed Liberson has a counterpart in John Friedmann.

Back in 2013, Friedmann was one of the first residents to raise community awareness about the emerald ash borer, which was discovered in Michigan in 2002 but had largely flown under the radar of the general public.

Friedmann, a self-described “tree guy,” has always objected to the city’s handling of the pest, starting with the Chicago Park District’s decision not to treat any of its ash trees, period, from the very beginning of the infestation. Now he takes exception to the surrender by Streets & San.

“At no level does it make sense, it’s so short-sighted,” Friedmann said. “Allowing an entire species of tree to be wiped out — we don’t know what we’re losing.”

Working with community organizations including the Horner Park Advisory Council and the North River Commission, Friedmann successfully spearheaded efforts to raise funds to treat Horner Park’s 65 ash trees, which have received regular inoculations and have all remained healthy.

Emerald ash borer larvae create a telltale tunneling pattern. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Emerald ash borer larvae create a telltale tunneling pattern. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

At the moment, the most effective treatment method is to inject an insecticide into a tree’s trunk, which kills the larvae that create the ash borer’s telltale tunneling effect. Researchers have also been working to breed borer-resistant varieties of ash and have been investigating “bio-controls” as well, such as (very carefully) releasing natural ash borer predators into the environment.

The results of some of these experiments have been encouraging, but it will take years to determine their ultimate effectiveness, said Tom Tiddens, supervisor of plant health care at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

“We don’t have anything to out and out stop this,” Tiddens said.

If there’s even a remote silver lining to the ash borer infestation, it’s that communities have finally learned a lesson they failed to take away from Dutch elm disease, which killed more than 75 million elms in the U.S.

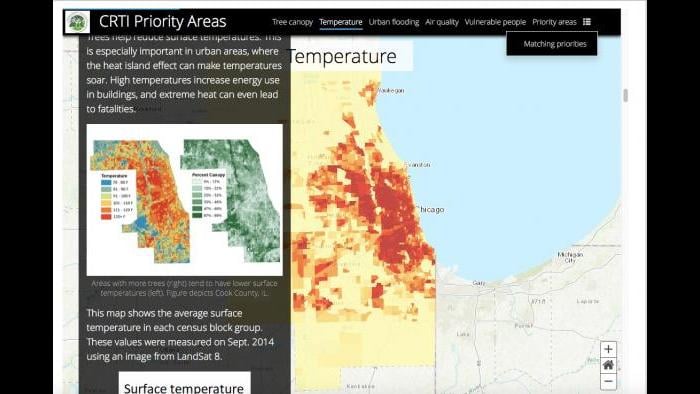

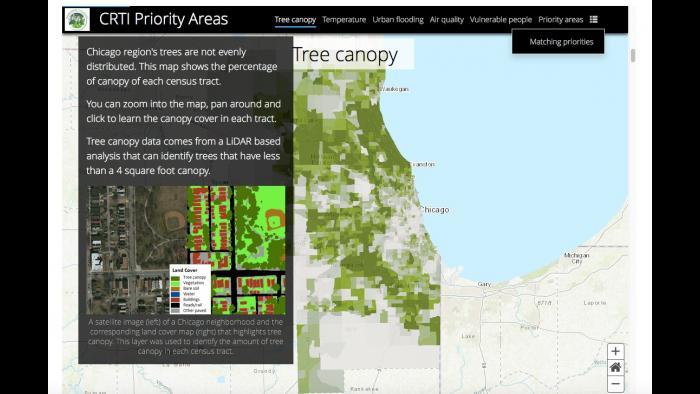

“It’s drawing attention to the problem of having too much of one tree,” said arborist Melissa Custic, coordinator of the Chicago Region Trees Initiative (CRTI) at Morton Arboretum.

Indeed, one of the primary trees planted to replace elms was the ash, said Tiddens. “We made a little mistake.”

Diversity is key to reforesting an area in the wake of a blight, the arborists agreed, creating resiliency not only against existing pests but those still to come. In that sense, the city’s decision to cut bait on the ash and populate parkways with a mix of other trees seems wise. (Chicago Botanic Garden has developed a list of the 40 best trees to plant going forward, accounting for climate change.)

The exception to that rule would be healthy, mature ash. Custic said there’s value in continuing to treat the larger healthy trees, such as Liberson’s, if for no other reason than they’re leafier than any replacement sapling would be.

“It seems almost intuitive, the bigger the tree, the bigger the benefit,” Custic said. ”I do hope the people who can, will keep treating [their ash] so that we have these big legacy trees.”

Trees are considered green infrastructure, she explained, and have been shown to contribute to a community’s well-being in ways both expected and surprising. There are the obvious advantages, like the cooling effect witnessed by Liberson, the amount of carbon dioxide they pull from the air and the important role trees play in supporting wildlife. But Custic said studies have also shown a correlation between the presence of trees and the reduction of crime, as well as increased test scores among students who have access to views of trees.

With climate change, a robust canopy cover is more important than ever, she said, and Chicago is already well below its target.

“The lowest canopy we should aim for, for an urban area to be resilient, we should be aiming for 40%,” Custic said.

The seven counties in the Chicago region are at 18%, she said, with some areas as low as 3%. A series of interactive maps created by CRTI show the relationship between canopy cover and temperature, with heat islands popping up in the absence of trees. Overlay canopy cover with socioeconomic data, and the inequality of where trees are distributed is plainly evident, Custic said. (Click here to view the presentation.)

“It’s important to get canopy cover everywhere,” said Custic, which is why Chicago Region Trees Initiative is focused on planting trees in areas with the greatest need.

But losing cover in greener neighborhoods like Ravenswood Manor negates positive action elsewhere, moving the needle in the wrong direction.

That’s the point that John Friedmann has been making.

“If you lose these big trees, you’re not getting an [equal] replacement. It really is anti all the other environmental initiatives,” he said. “Allow the mature trees to keep living.”

Mature ash trees provide significant canopy cover. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

Mature ash trees provide significant canopy cover. (Patty Wetli / WTTW News)

There’s another reason Friedmann refuses to give up on the ash.

He still believes a comeback is possible. And he has history, and the chestnut, on his side.

The American chestnut was once one of the mightiest trees in the U.S. Dubbed the “Redwood of the East,” it made up 25% of a forest that stretched from Maine to Florida and west to Ohio. Then along came a fungus that hitchhiked its way from Japan and felled 4 billion chestnuts in a handful of decades. Four billion.

The devastation was massive, but not complete. Some American chestnuts survived, including a group grown from seeds planted outside the plague’s reach. Today those trees and their descendants form the largest remaining chestnut stand in the U.S., found in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Scores of scientists from across the country now pay annual pilgrimage to La Crosse, where the stand has become the “largest laboratory in the fight against blight,” according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Plant pathologists continue to simultaneously protect the surviving chestnuts while also using them as guinea pigs for new treatments and breeding approaches, more than 100 years after the blight was first identified.

“Science can do all sorts of wonderful things given enough time,” Friedmann said, but only if specimens outlast the purge, which is why he continues to plead for the city to reverse course on its ash policy.

Meanwhile, Friedmann’s immediate goal is to set up an endowment that would pay for treatment of Horner Park’s ash in perpetuity or until a cure is discovered, in effect creating an ash sanctuary.

“It could be a mini-arboretum,” Friedmann said. “Somebody’s got to save these things.”

Contact Patty Wetli: @pattywetli | (773) 509-5623 | [email protected]