The Hall of Birds at the Field Museum is jam-packed with hundreds of the world’s most diverse, colorful and exotic specimens, all carefully arranged in lifelike detail.

But until recently, the person behind many of them was largely unknown, even to Field Museum employees.

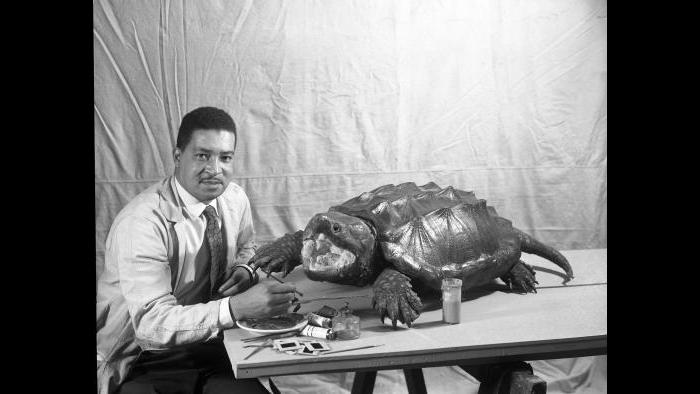

“Carl Cotton was a Field Museum taxidermist, he started here in 1947 and he worked here until 1971,” said Tori Lee, an exhibition developer at the museum. “We knew practically nothing about him other than we’ve seen some really cool pictures of him in the photo archives and we were like, this is a black man who was hired at the Field Museum in 1947 – not a very typical story.”

Cotton was the Field Museum’s first African American taxidermist, and he’s now the focus of an exhibit honoring his legacy and craftsmanship.

The show, called “A Natural Talent: The Taxidermy of Carl Cotton,” also details Cotton’s upbringing on the South Side of Chicago in the 1920s and ‘30s.

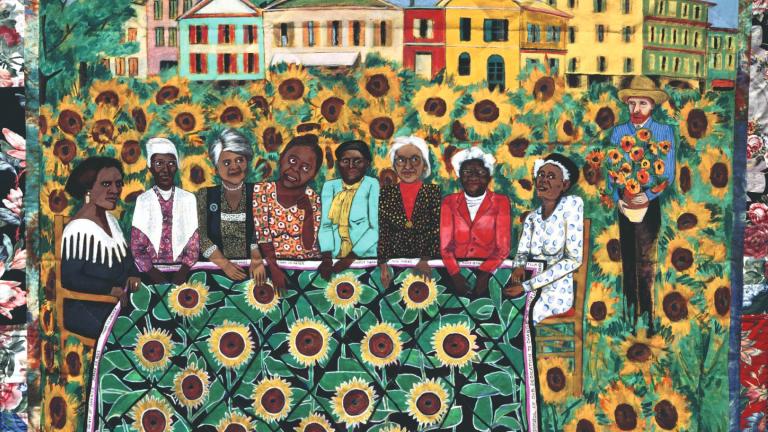

“It was also this time of huge cultural booming, it was this black cultural renaissance happening here in Chicago. Carl grew up with people like Gwendolyn Brooks, with Charles White, Timuel Black. He grew up with artists. He himself he was kind of a nontraditional artist as a taxidermist,” Lee said.

That artistry is evident in the many dioramas and displays Cotton put together across the museum. He worked not only on birds, but also with reptiles and insects.

“He was 100% an artist, he was a taxidermist, but for most people who do taxidermy, taxidermy is a form of art,” Lee said. “He really used all of the skills, his understanding of love and nature, his talent, his skill as an artist to create these displays.”

A focal point of Cotton’s work at the Field is the Marsh Birds of the Upper Nile River diorama, an intricate portrait of specimens like the shoebill stork and 21 other types of birds from Uganda.

Visitors to the exhibit will find archival footage that shows Cotton putting together the display — and not only the birds, but also the mud and plants, which were handmade with wax.

“The time and the effort it took to make every element is just something people don’t necessarily see or appreciate when they walk through some of these halls … every single element of this was handcrafted by a person,” Lee said.

The Cotton retrospective is also something of a departure from how the Field usually puts exhibits together. This one involved tracking down Cotton’s family members on social media, combing through museum archives and interviewing old friends to help tell his story.

It also became a personal project for Lee, who sees parallels between Cotton’s life and work, and her own.

“It’s important to acknowledge that black history has happened here at the Field Museum. And it’s happened for a long time,” Lee said. “I think even now museums, including the Field Museum, have issues with diversity, equity, representation, and it’s really important to me to see both black people in the museum and as the subject of exhibitions in a way that is produced by them.”

Note: This story was first published Feb. 10, 2020.