(Richard Schneider / Flickr)

(Richard Schneider / Flickr)

What lies below the surface of the Chicago River today is not what it was a century ago, when the river served as a dumping ground for the city’s famous stockyards and meatpacking plants.

Although the river still struggles with pollution, especially during and after storms, it has become significantly cleaner in recent decades.

Now, the Chicago nonprofit Current wants to give you real-time updates on the river’s water quality with just a few taps on your phone, much like checking the weather.

The pilot project, called H2NOW, will measure the levels of microbial pollution in the river and display the results online, eventually on a mobile-friendly website.

If all goes well, Current plans to make the data available to the public later this year.

Current’s staff says the effort is the first of its kind in the U.S. and that the technology could at some point be used to measure pollution levels in Lake Michigan and other bodies of water.

“We have not discovered a program like H2NOW that is publicly conveying data like this in real time,” said George Brigandi, partnership and development manager for Current, which formed in 2016 to pilot water technology innovations and evaluate their potential use for government and business partners. “So if you wanted to go kayak or canoe or fish on the river, there’s nothing you could do [right now to check] the water quality to maybe make a more educated decision, a safer decision.”

Traditional methods for measuring water pollution levels involve collecting samples and sending them to a lab for testing, a process that can take one to two days. Recent advancements in rapid water testing have made it possible to measure pollution levels in about four hours, as demonstrated by UIC researchers in a 2017 study.

Current’s project takes a shortcut made possible by a series of cylinder-shaped sensors, three of which were recently lowered into the river’s North Branch, South Branch and Main Stem.

A sensor for measuring water quality developed by RS Hydro (Courtesy RS Hydro)

A sensor for measuring water quality developed by RS Hydro (Courtesy RS Hydro)

The sensors, developed by England-based RS Hydro, measure reflected light beneath the river’s surface to estimate levels of fecal coliform, a commonly used indicator of microbial pollution and the one used by the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency to assess water quality, said Svetlana Taylor, Current’s senior analyst.

Once a sensor is deployed and begins taking measurements, the technology goes to work fast, spitting out a number on Current’s computers within seconds.

Current is still testing the sensors, but the goal is to communicate the water quality readings publicly on at least an hourly basis, if not more frequently. That’s a big step up from the monthly measurements regulators take today, said Steve Frenkel, the group’s executive director.

“You’re getting one data point per location per month, up and down the water,” he said. “And so we thought, ‘Can we build on that?’”

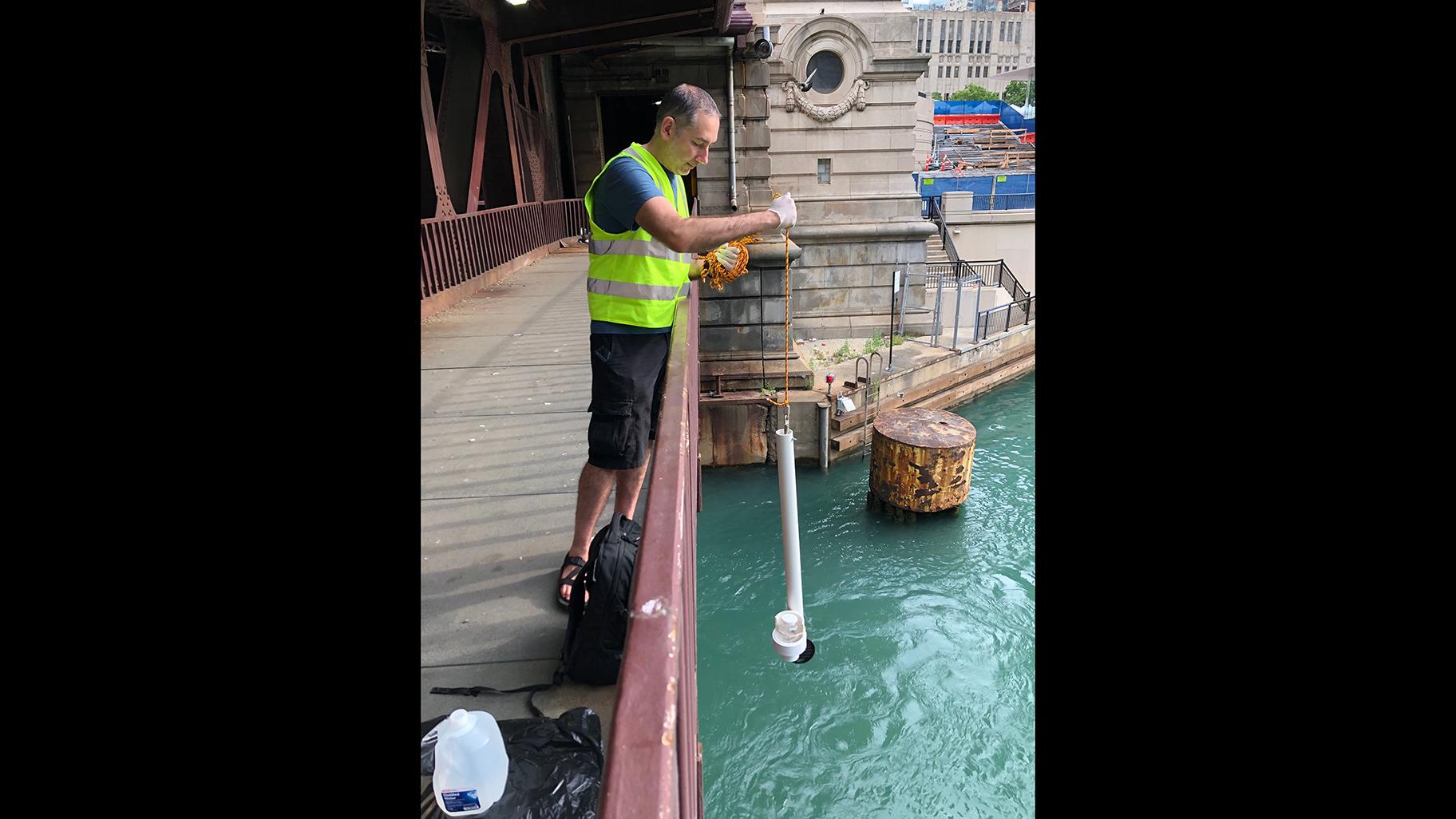

Steve Frenkel, Current’s executive director, conducts water sampling in the Chicago River. (Courtesy Current)

Steve Frenkel, Current’s executive director, conducts water sampling in the Chicago River. (Courtesy Current)

Although Current hopes that Chicagoans will turn to H2NOW to check on pollution levels before, say, climbing into a kayak, the organization does not plan to provide warnings or guidance about when it is or isn’t safe to access the river, Brigandi said.

Instead, when users access H2NOW on Current’s website, they’ll see material aimed at educating them about water quality and recreational opportunities along the river, in addition to water quality data.

“We thought that if we could bring that information to the public in a scientifically robust and transparent way, that could go far toward helping to elevate the river as an appealing waterway for recreation and commerce,” Frenkel said.

Eventually, Current thinks the data could help shape policies and practices with environmental, commercial and recreational consequences, such as when, how and by whom the river is used.

Brigandi said the group is working with Israel-based data analytics company IOSight to process and analyze pollution data, using artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to understand the impact of varying levels of bacteria.

Current won’t disclose how much money has gone into H2NOW so far; Brigandi says only that the organization has raised funds from the Chicago Community Trust and the group’s partners.

That includes governmental agencies, like the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago and the city’s Department of Water Management; universities, such as the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and corporate partners, including businesses in the food beverage industry.

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and other elected officials jump into the Chicago River during the “Big Jump” event in September 2017. (Courtesy Metropolitan Water Reclamation District)

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and other elected officials jump into the Chicago River during the “Big Jump” event in September 2017. (Courtesy Metropolitan Water Reclamation District)

Since launching three years ago, Current has teamed up with the MWRD to evaluate a new wastewater treatment technology that can efficiently remove phosphorus, which contributes to harmful algal blooms. The nonprofit is also piloting a program that would allow companies in Illinois to trade nutrient pollution credits, with a goal of reducing the overall amount of pollution in watersheds.

As for H2NOW, Frenkel said Current is in the process of calibrating the three sensors that were recently deployed. The group then plans to spend several months collecting and analyzing data to ensure that the sensors are operating correctly.

For Frenkel, H2NOW is about challenging a perception by many that the river is still as polluted as it once was.

Does that mean he envisions Chicagoans swimming in the river sometime soon? Although not an explicit goal of the project, Frenkel said it’s a long-term goal for him and others.

“We’ve seen that urban waterways around the world are moving toward becoming swimmable, and down the road the Chicago River could get there,” he said.

Contact Alex Ruppenthal: @arupp | [email protected] | (773) 509-5623

Related stories:

Open-Water Swim in Chicago River Delayed, New Goal September 2020

UIC Expands Rapid Water Testing at Chicago Beaches

Shedd Kayak Trips Encourage Paddlers to Explore and Restore Chicago River

‘Blue-Green’ Chicago River Corridor Would Generate $192M Yearly, Analysis Shows

Trash Removal Project Adds 7-Mile Stretch of Chicago River