In a state-of-the-art facility in downtown Chicago, the next generation of bionic prosthetics is being developed at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab.

Terry Karpowicz, who lost his leg in a motorcycle accident 40 years ago, has been working with a team of engineers and clinicians to help develop a new bionic leg. He’s excited about what it could do for him.

“I’m a sculptor so I need my hands and having a leg to allow my hands to be free is ... everything,” said Karpowicz. “Having a motorized leg allowing me to move my hands – and being ambulatory is everything.”

He says that compared to previous prosthetics he’s used, which were not motorized, the bionic limb he is testing allows him to walk with a natural gait and even climb stairs.

“This is probably 50% better because it allows me to save energy,” said Karpowicz. “It helps me move as opposed to me initiating the muscle movement to pull it along. So I would say this would save me hours of time.”

Levi Hargrove is the director of the AbilityLab’s center for bionic medicine and is focused on coming up with better ways to control bionic legs and arms.

One of the unique things about the leg that Karpowicz is helping test and evaluate is that its makers have made the design open source – meaning that other researchers can copy the design and work to improve it.

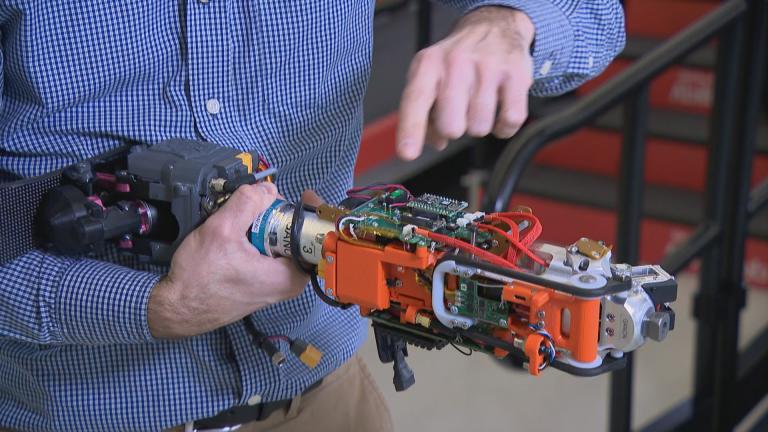

Hargrove said the latest iteration of the team’s bionic leg has a few unique design features.

“First off it is reconfigurable, so we can change the alignment or the position of the knee with respect to the ankle. It also has very powerful motors – they actually come from the drone industry – you think of the little helicopters that are remote control and fly around … we’ve been able to harvest some of that technology. Design some sophisticated control strategies to allow Terry to walk. So what we’re really working on is making it smooth, intuitive and seamless so that when Terry takes a step, whether he’s walking on level ground or going up and down slopes or stairs it will respond to his intentions.”

To make that possible, the leg has 64 sensors that measure all aspects of its movement.

“So each step it is deciding – when the foot comes off the ground – what we think Terry might want to do and when the foot hits the ground what Terry will want to do, and then it will program in the appropriate behaviors so Terry can walk on the device,” said Hargrove.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning allow the device to learn Karpowicz’s walking patterns and intentions and improve over time.

“Think of it like predictive typing or voice recognition,” said Hargrove. “Algorithms like that are programmed in the leg but they are listening to 30 or 40 signals at the same time rather than just your voice. Or just a keyboard. So it is pretty sophisticated.”

In fact, according to Hargrove, this latest prototype, which was initially funded by the U.S. Army and now by the National Institutes of Health, is as advanced as it gets. It’s the culmination of more than a decade of work.

But his team is constantly working on ways to improve it – especially when it comes to making it lighter and more robust.

“We want to make sure that Terry has the freedom to move wherever he wants to move because we are so confident in the hardware that we don’t have to worry about something breaking,” said Hargrove. “Another project that we are very excited about is we are going to put the sensors inside of the body. So perhaps not with Terry but with someone we are going to have little pill-like sensors that we inject inside of their muscle and we’ll read the signals on the inside as opposed from the outside. So this allows us to get a really high-fidelity estimate of what the person is doing or thinking.”

Hargrove says that one of the reasons the AbilityLab has been so successful in advancing prosthetic design is that it brings together scientists, engineers, clinicians and patients in one space.

“Being able to bring all of that together in one group at the same time is really impactful and it allows us to make advancements that otherwise would take decades or at least a number of years relatively quickly,” said Hargrove.

Ultimately, the goal is to make prosthetics so reliable that they will scarcely need maintenance.

“Hopefully we’ll get to the point where you put it together once and it’s going to last for months without having to do any tweaks or having to open it up and do any kind of maintenance,” said Hargrove. “Kind of like, if you think of a vehicle, you might need to take it in for servicing once a year.”

And while it may still be a year or two before Karpowicz is able to take a new leg home, he’s eager to see how it will change his life.

“I’m really looking forward to it,” said Karpowicz. “To turning me loose in the studio and seeing what it can do for me in terms of making my life easier.”

Related stories:

At Museum of Science and Industry, a Brave New World of Wearable Tech

UChicago Researchers Get $3.4M to Develop Brain-Controlled Prosthesis

New Type of Wearable Electronics Could Boost Stroke Patients’ Recovery

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago Unveils New AbilityLab

Paralyzed Man Regains Sense of Touch with Robotic Arm