For its big summer show this year, the Art Institute takes a fresh look at the early modern artist, Edouard Manet.

WTTW News visited the exhibition “Manet and Modern Beauty” before its public opening in May.

TRANSCRIPT

Brandis Friedman: Chic young women with fashionable clothing – and captivating beauties without. Stylish men, and moody men. Couples in conversation, delicate still lifes and fading flowers.

These are among the later works of Edouard Manet, who influenced the development of Impressionism.

Édouard Manet. “Boating,” 1874–75. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

Édouard Manet. “Boating,” 1874–75. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

The artist had an eye for the beauty and material culture of 19th century French society. The exhibition spotlights that and more.

Gloria Groom, chair of European Painting and Sculpture, Art Institute of Chicago: It’s more about this artist that we all think we know, and the last four or five years of his life and how he had to shift into another mode, because of some physical limitations, and what he did with that shift and how he, during that time, created some of the most lush and compelling works of his career.

Friedman: Manet, depicted here in a painting by a friend, was stricken with syphilis.

He had left Paris at his doctor’s advice to attempt to recuperate in the countryside.

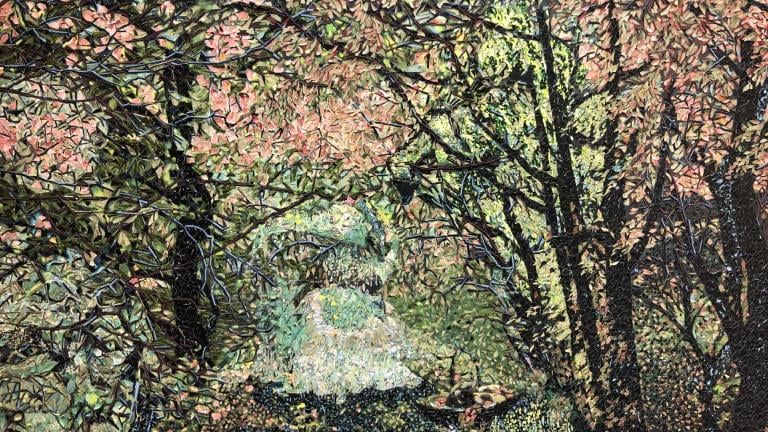

Groom: He’s having to rethink what it means to be an artist, but his world was also shrinking, so the cafes and cabarets he used to attend, the opera, the racetracks, those are no longer easy for him to get to. So what does he do? He recreates modern life in his studio.

While he was in the country he did these landscapes and gardenscapes because that’s what he had in front of him, but he would bring those back to Paris to his studio, and he would have the model come in and he would set up a scene as if the model is drinking a beer out in front of a garden, and so those paintings that he did in the suburbs become the backdrops for the completely staged picture of modern life that he was doing in his studio.

Friedman: The show includes gems from the Art Institute collection and significant loans such as the lush masterpiece “In the Conservatory,” borrowed exclusively for the Chicago exhibition from the State Museum in Berlin.

Édouard Manet. “In the Conservatory,” about 1877–79. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

Édouard Manet. “In the Conservatory,” about 1877–79. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

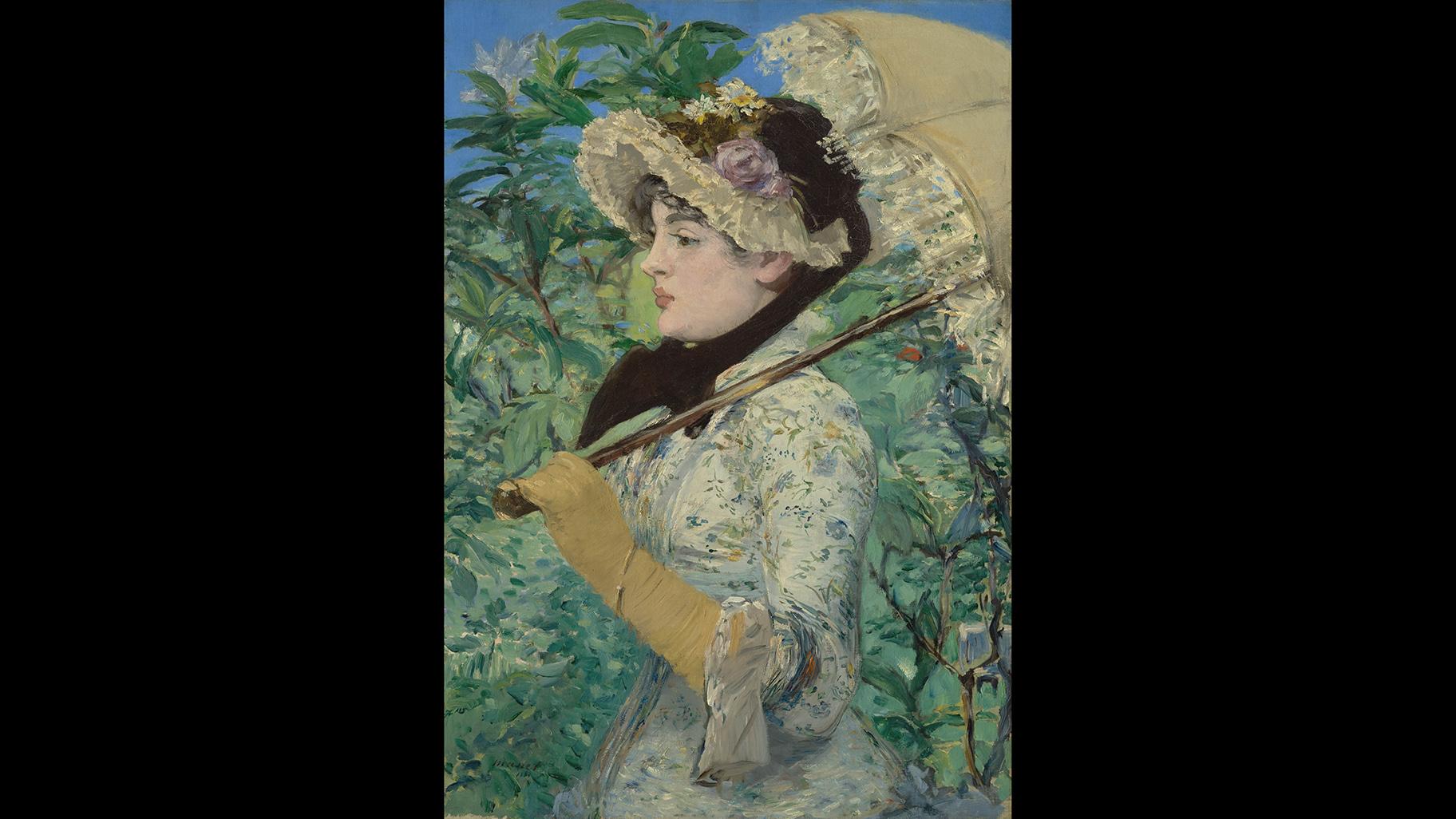

The Art Institute’s partner in the show – the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles – contributed a feminine symbol of springtime called “Jeanne.”

Groom: Jeanne is the superstar of this exhibition.

For the critics it was like he’s finally done it. He’s finally hit it out of the ballpark. She’s easy to understand, she’s la Parisienne, she’s decoration, she’s femininity, she’s fashion, she – it ticked off all the boxes of something that the critics thought was just amazing. Instead of the more ambivalent, difficult, non-narrative paintings that he had exhibited up to that time, here was something that was striking back to the Renaissance – a woman in profile, but an idealized woman, an allegory of spring.

Édouard Manet. “Jeanne (Spring),” 1881. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Édouard Manet. “Jeanne (Spring),” 1881. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Friedman: “Manet and Modern Beauty” also has a collection of the flower paintings cherished by his friends, scenes of country life and illustrated letters that he wrote.

The letters don’t mention his failing health.

Edouard Manet died at age 51 in 1883.

Groom: He was a very upper middle-class artist, very much a gentleman, very erudite, but he also would not let anyone know about his illness. Only his closest friends would have known, because his letters are, “It’s raining, I can’t paint today,” or, “I’m using a bad pen, excuse the handwriting,” so any excuse to make up for the fact that he really was declining in health and it was causing problems for him, but you’d never know that through his art which is always upbeat and joyous as he wanted it to be.

Friedman: Manet spent his final years painting simple pleasures – and complex companions.

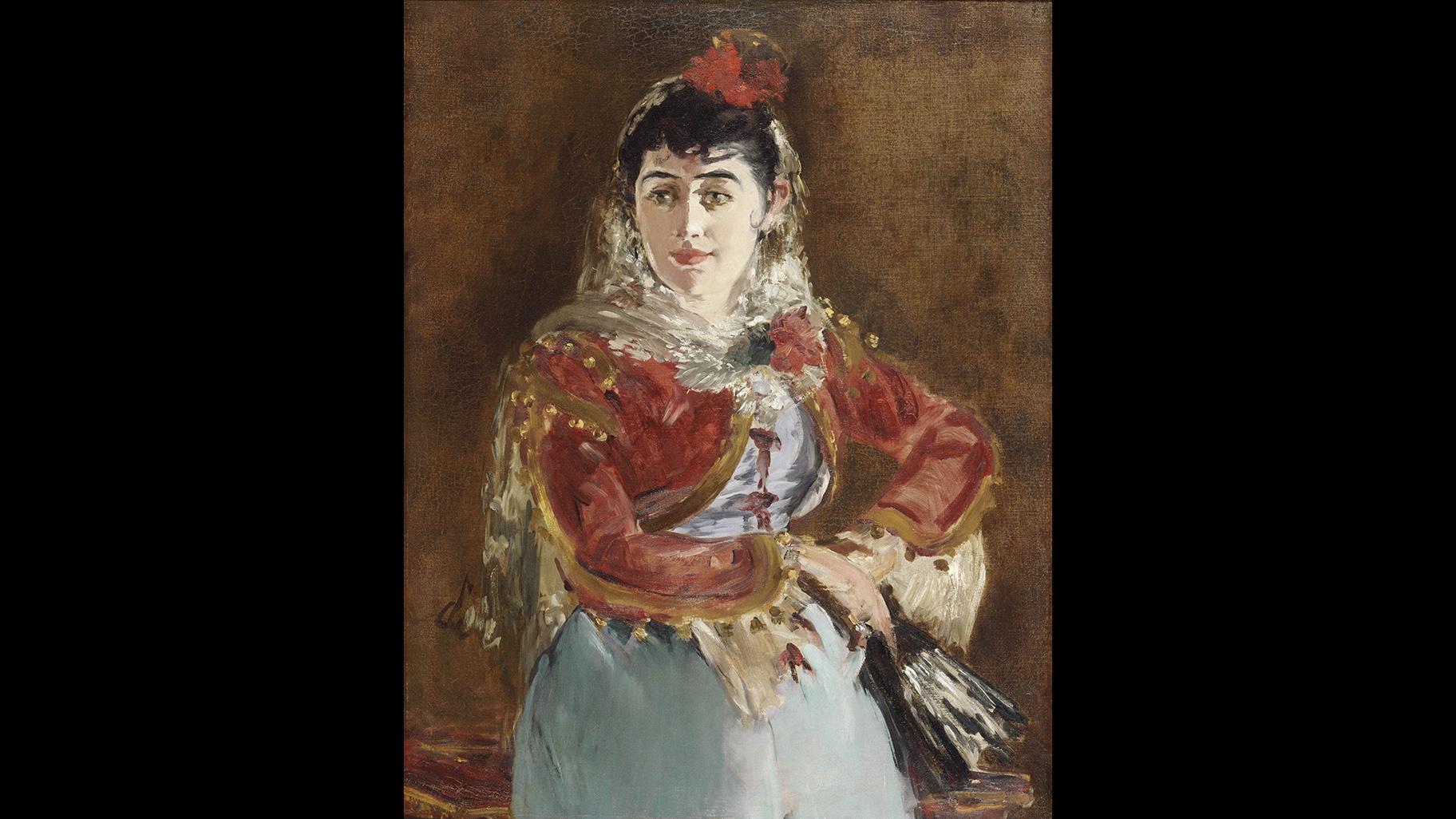

Groom: He was an artist who really appreciated smart women, and women that liked his art, but also women who were not necessarily the angel of the house. They were out in the world, rather than home.

He was very comfortable around women, especially intelligent women.

Édouard Manet. “Portrait of Émilie Ambre as Carmen,” 1880. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Edgar Scott, 1964. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Édouard Manet. “Portrait of Émilie Ambre as Carmen,” 1880. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Edgar Scott, 1964. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“Manet and Modern Beauty” opens on Sunday at the Art Institute of Chicago and runs through Sept. 8, 2019.

Note: This story was originally published May 23, 2019. It has been updated.

Related stories:

‘Hamilton’ Exhibition Brings 18th Century Life into 2019 Reality

At Museum of Science and Industry, a Brave New World of Wearable Tech

New Field Museum Exhibit to Showcase Stunning Wildlife Photography