After two decades with the Chicago Department of Public Health, Dr. Julie Morita will leave her post as commissioner in June to begin working at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as its executive vice president.

“This has been the most difficult decision in my life,” said Morita, who grew up and still lives in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood. She says she would’ve been happy to stay in her role and work with Mayor-elect Lori Lightfoot, but couldn’t pass up the opportunity. “This is the only job that could’ve lured me away from Chicago and the Chicago Department of Public Health.”

The origins of Morita’s career in public health can be traced back to a children’s book she idolized as a child: “Nurse Nancy.” In the book, Nancy pretends to be a nurse and treats neighborhood kids. “Helping people has always been my priority,” she said.

While Morita wanted to be a nurse, her father also encouraged her to “think beyond traditional female roles” and consider becoming a doctor or dentist, like him.

A Chicago Public Schools student, Morita was interested in math and science, which led her to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to pursue an engineering degree. “But engineering didn’t have that human interaction, person-to-person (connection) I was hoping for,” said Morita, who ended up changing her major to biology to pursue a career in medicine.

She attended medical school at the University of Illinois at Chicago and completed her residency at the University of Minnesota. “I became a pediatrician, which is a great fit for me. I loved taking care of kids and the prevention aspect of pediatrics,” she said. “There’s so much about preventing injuries or getting sick.”

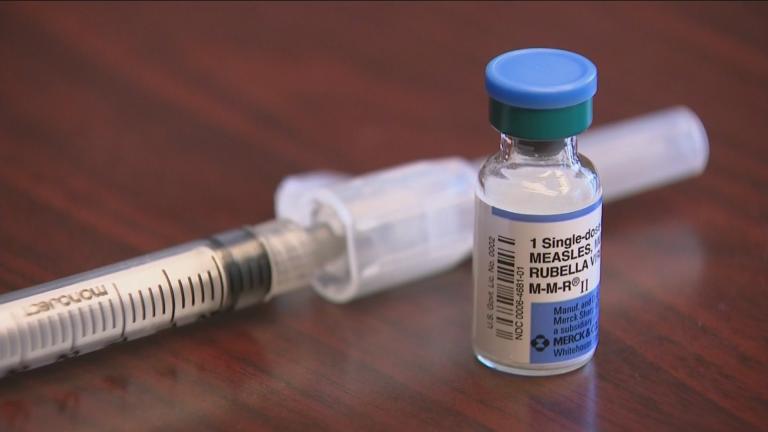

About four years after becoming a pediatrician in Tucson, Arizona, Morita moved to Atlanta to join the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where she worked as an epidemic intelligence service officer and focused on vaccine-preventable diseases, like streptococcus and meningitis.

In 1999, Morita returned to Chicago and began working as CDPH’s medical director for immunizations. She says it was that role in which she really began focusing on health disparity and equity.

She noticed that while most Chicago children received the proper vaccines, not all did. “In some neighborhoods, less kids were vaccinated,” she said. The CDPH worked to address the gap by focusing its attention and resources on areas with lower vaccination rates, and coupled that with a public education campaign. “We had a lot of success in helping eliminate some of those disparities,” she said.

During the course of her career, Morita led efforts to address pandemic influenza, meningitis and Ebola. The work was both “incredibly challenging and rewarding,” said Morita, who was promoted to chief medical officer in 2012.

Three years later, she was tapped to be the commissioner of the department by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who called her forthcoming departure a loss for Chicago.

“For two decades, Dr. Julie Morita has been a relentless champion for health equity at the Chicago Department of Public Health,” Emanuel said in a statement. “The City of Chicago’s loss is the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s gain. She was the first Asian American to lead the department and leaves behind a strong legacy – groundbreaking tobacco legislation, higher HPV vaccination rates, record low new cases of HIV, strong response to the Ebola crisis, and Healthy Chicago 2.0, a plan that engaged partners in every sector to address the root causes of health.”

Morita attributes the progress that’s been made in the past 20 years to CDPH staff. “People working here are incredibly passionate and committed to addressing health and focusing on disparities,” she said.

Of her accomplishments, Morita said she was most proud of her work on HPV vaccinations and tobacco legislation, though she’s a bit wary of the rise in e-cigarettes and vaping among youth.

Under Morita’s tenure, the city increased the legal age to purchase tobacco products to 21, which Morita believes contributed to a drop in youth smoking rates to just 6 percent of high school students in 2017.

“(Vaping) now has the potential to wipe out all the progress that’s been made in preventing young people from smoking,” she said. “(Vaping) is a public health threat and we need to pounce on it.”

She’s hopeful the statewide law raising minimum purchasing age to 21 will help make tobacco products less accessible to youth. “I’d love for Wisconsin, Indiana and Iowa to do the exact same thing,” she said.

Morita hopes the next commissioner and administration continues CDPH’s work on promoting health equity and addressing the social determinants of health that contribute to disparities, such as access to healthy foods, transportation and health care. She also hopes they continue to address race equity and “look at the policies and systems we have in (place) to make sure they don’t perpetuate racist systems and structures,” she said.

Morita’s first day at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is set for June 24. She says she’s not sure when her last day at CDPH will be but will “help work with the new administration to make it an easy transition. ... I remain committed to Chicago and the residents of Chicago and my home,” she said. “I hope to make a positive impact on other jurisdictions when I leave.”

Related stories:

Illinois Has Confirmed 154 Cases of Potentially Deadly Fungal Disease

Illinois Raises Smoking Age to 21

With $1.5M Grant, UI Cancer Center to Address Disparities in Chicago