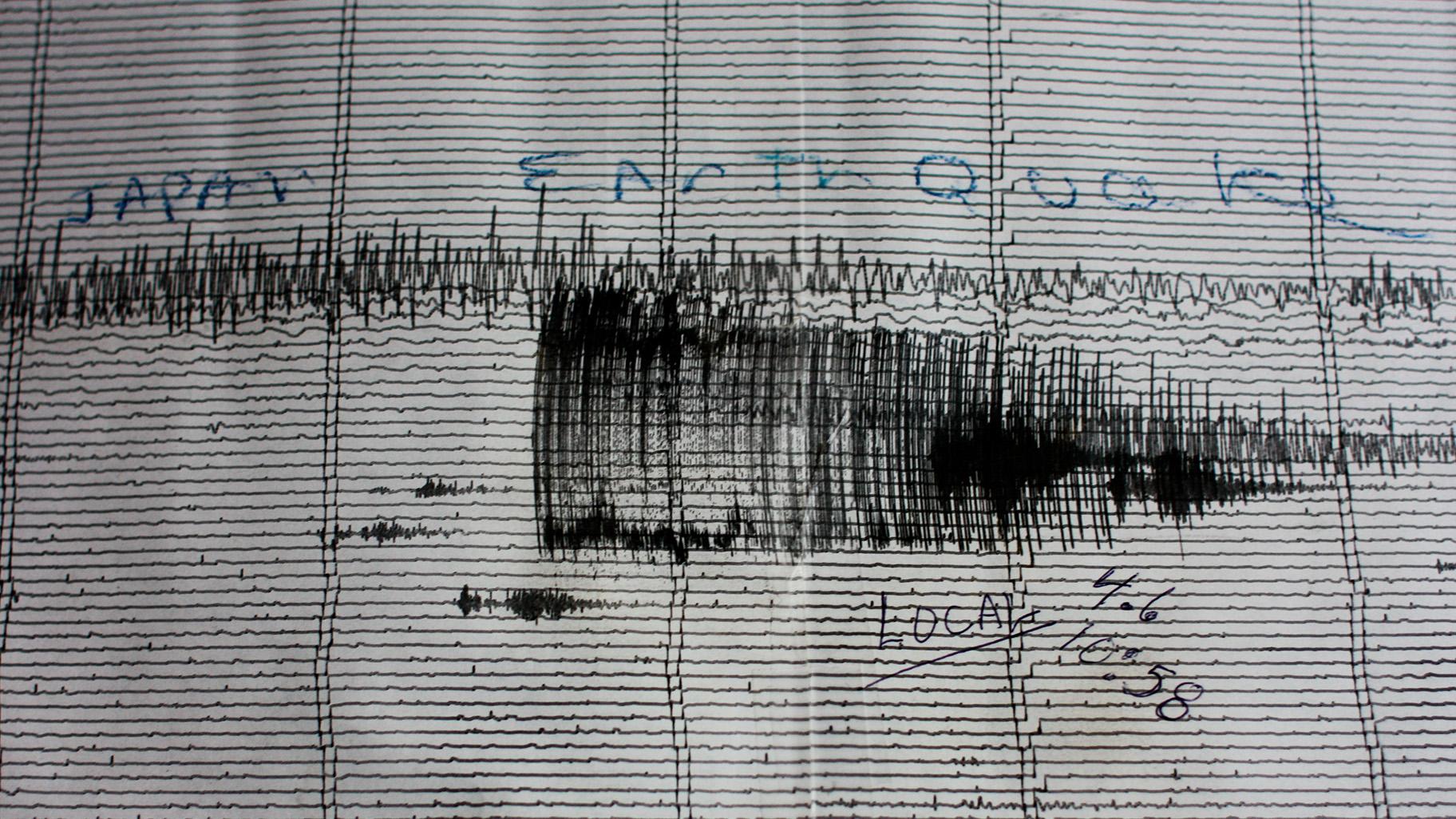

The seismographs at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park visually depict the suddenness and intensity with which the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake devastated the islands of Japan. (Joe Parks / Flickr)

The seismographs at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park visually depict the suddenness and intensity with which the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake devastated the islands of Japan. (Joe Parks / Flickr)

You – yes, you – could help scientists predict future earthquakes.

A new project launched this winter by Northwestern University faculty and students is soliciting help from volunteers to sort through data from tens of thousands of seismograms, graphs that depict ground motions of the Earth’s surface with a series of squiggly lines.

Typically, reading a seismogram requires some level of expertise: To the untrained eye, it would be nearly impossible to tell which lines are caused by a tremor and which indicate a storm, a falling tree or a subway train rattling by.

But for their new project, Northwestern seismologists teamed up with doctoral candidate Boris Rösler, who wrote a computer code that transformed seismic frequencies into audible pitches, which are much easier to distinguish.

Earthquakes, for example, trigger a sudden release of energy that sounds like a slamming door. Tremors, meanwhile, product a slow release of energy that sounds more like a train rumbling over tracks.

By taking a quick online video tutorial, volunteers learn how to classify these sounds and sort them out from more ambiguous noises, which can be caused by construction, strong winds or even loud sporting events. Compared to the more powerful sounds produced by earthquakes and tremors, these events produce “background noise” that can sound like anything from a whale to a whistle.

“With the audio files, volunteers don’t need to be seismologists or geologists,” said Vivian Tang, a seismologist and doctoral candidate who created the project, in a statement. “They can just listen to these files from anywhere and distinguish whether it’s an earthquake, tremor or just background noise.”

A seismogram (California Office of Emergency Services)

A seismogram (California Office of Emergency Services)

The project could help solve a major issue within the seismology field: Data collected from seismograms around the world is already available in a massive open-access archive. But there aren’t enough scientists to go through it all, which got Tang thinking about all the valuable information that could be hiding in plain sight.

Working with Kevin Chao, a data science scholar at the Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems and an expert in dynamically triggered seismic activity, Tang conceived the new project, called “Earthquake Detective.”

With the help of volunteers, Tang and other seismologists should be able to learn more about seismic events and the conditions under which they occur.

“Classifying this data will help us paint a more complete picture of when larger earthquakes may trigger smaller ones or tremors,” said Suzan van der Lee, a seismologist and professor of Earth and planetary sciences in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, in a statement. “Then we can learn what conditions are favorable and what factors need to align to allow them to happen, which ultimately also might inform the reverse of how small seismic events interact with big ones.”

Since the project’s launch several months ago, nearly 900 volunteers have been working to classify more than 16,000 sounds. After one file, or set of sounds, is analyzed by at least 10 people, the case is considered closed.

For now, the project is focusing on seismic events in North America, but it will add audio files from seismograms in other regions as the effort continues.

Once volunteers have listened to and classified enough of the audio files, seismologists and data scientists will be able to enter the data into seismic models that could help them better understand how, where, when and why earthquakes happen, according to the Northwestern team.

To participate or for more information about the project, visit its website.

Contact Alex Ruppenthal: @arupp | [email protected] | (773) 509-5623

Related stories:

Illinois to Participate in ‘The Great ShakeOut’ Earthquake Drill

Anniversary of 1812 Illinois Earthquake Ushers in Preparedness Month