It’s long been believed that residential segregation was a result of personal choices. But a new book argues segregation happened by design.

In “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” author Richard Rothstein looks at how segregation is the result of housing policies created by the government and dating back to the New Deal.

One of those policies is public housing, which was segregated from the start, Rothstein says, by building separate residences for African-Americans and whites.

“The other major program that the federal government followed to create segregation was the Federal Housing Administration’s explicit program to move the white population into single-family homes in the suburbs,” said Rothstein, a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute.

As part of the program, the government subsidized construction in exchange for two promises: the homes would never be sold to African-Americans, and the deed to a house include language to prohibit those homes from being resold to African-Americans.

“This is how this country became suburbanized – on an all-white basis,” Rothstein said.

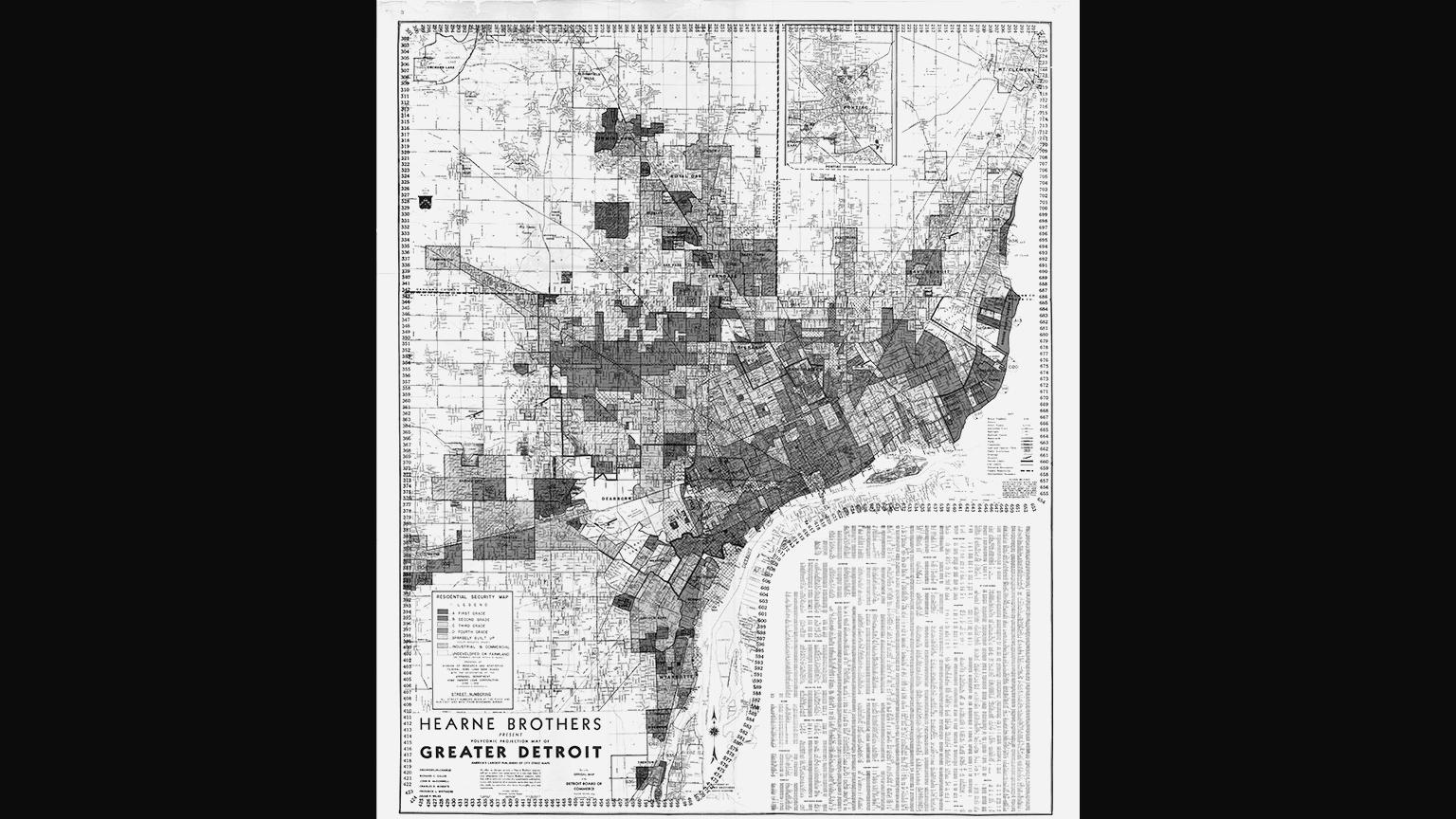

A redlining map of Detroit, created by a New Deal housing agency, to distinguish where African-Americans resided to warn appraisers not to approve loans. (Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company)

A redlining map of Detroit, created by a New Deal housing agency, to distinguish where African-Americans resided to warn appraisers not to approve loans. (Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company)

Rothstein joins Brandis Friedman to discuss those policies and how they ultimately contributed to racial disparities in education, jobs and income.

Below, an excerpt from “The Color of Law.”

When, from 2014 to 2016, riots in places like Ferguson, Baltimore, Milwaukee, or Charlotte captured our attention, most of us thought we knew how these segregated neighborhoods, with their crime, violence, anger, and poverty came to be. We said they are “de facto segregated,” that they result from private practices, not from law or government policy.

De facto segregation, we tell ourselves, has various causes. When African Americans moved into a neighborhood like Ferguson, a few racially prejudiced white families decided to leave, and then as the number of black families grew, the neighborhood deteriorated, and “white flight” followed. Real estate agents steered whites away from black neighborhoods, and blacks away from white ones. Banks discriminated with “redlining,” refusing to give mortgages to African Americans or extracting unusually severe terms from them with subprime loans. African Americans haven’t generally gotten the educations that would enable them to earn sufficient incomes to live in white suburbs, and, as a result, many remain concentrated in urban neighborhoods. Besides, black families prefer to live with one another. All this has some truth, but it remains a small part of the truth, submerged by a far more important one: until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state, and local governments defined where whites and African Americans should live. Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time. Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes—private prejudice, white flight, real estate steering, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation—still would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression. Segregation by intentional government action is not de facto. Rather, it is what courts call de jure: segregation by law and public policy.

De facto segregation, we tell ourselves, has various causes. When African Americans moved into a neighborhood like Ferguson, a few racially prejudiced white families decided to leave, and then as the number of black families grew, the neighborhood deteriorated, and “white flight” followed. Real estate agents steered whites away from black neighborhoods, and blacks away from white ones. Banks discriminated with “redlining,” refusing to give mortgages to African Americans or extracting unusually severe terms from them with subprime loans. African Americans haven’t generally gotten the educations that would enable them to earn sufficient incomes to live in white suburbs, and, as a result, many remain concentrated in urban neighborhoods. Besides, black families prefer to live with one another. All this has some truth, but it remains a small part of the truth, submerged by a far more important one: until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state, and local governments defined where whites and African Americans should live. Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time. Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes—private prejudice, white flight, real estate steering, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation—still would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression. Segregation by intentional government action is not de facto. Rather, it is what courts call de jure: segregation by law and public policy.

Residential racial segregation by state action is a violation of our Constitution and its Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment, written by our Founding Fathers, prohibits the federal government from treating citizens unfairly. The Thirteenth Amendment, adopted immediately after the Civil War, prohibits slavery or, in general, treating African Americans as second-class citizens, while the Fourteenth Amendment, also adopted after the Civil War, prohibits states, or their local governments, from treating people either unfairly or unequally.

The applicability of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to government sponsorship of residential segregation will make sense to most readers. Clearly, denying African Americans access to housing subsidies that were extended to whites constitutes unfair treatment and, if consistent, rises to the level of a serious constitutional violation. But it may be surprising that residential segregation also violates the Thirteenth Amendment. We typically think of the Thirteenth as only abolishing slavery. Section 1 of the Thirteenth Amendment does so, and Section 2 empowers Congress to enforce Section 1. In 1866, Congress enforced the abolition of slavery by passing a Civil Rights Act, prohibiting actions that it deemed perpetuated the characteristics of slavery. Actions that made African Americans second-class citizens, such as racial discrimination in housing, were included in the ban.

In 1883, though, the Supreme Court rejected this congressional interpretation of its powers to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. The Court agreed that Section 2 authorized Congress to “to pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery in the United States,” but it did not agree that exclusions from housing markets could be a “badge or incident” of slavery. In consequence, these Civil Rights Act protections were ignored for the next century.

Today, however, most Americans understand that prejudice toward and mistreatment of African Americans did not develop out of thin air. The stereotypes and attitudes that support racial discrimination have their roots in the system of slavery upon which the nation was founded. So to most of us, it should now seem reasonable to agree that Congress was correct when it determined that prohibiting African Americans from buying or renting decent housing perpetuated second-class citizenship that was a relic of slavery. It also now seems reasonable to understand that if government actively promoted housing segregation, it failed to abide by the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition of slavery and its relics.

Reprinted from The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein. Copyright © 2017 by Richard Rothstein. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Related stories:

The 2 Chicagos: What a New Poll Says About the City and Its Residents

‘America to Me’ a Story of High School in Black and White

The Economic Costs of Segregation – And Recommendations to Address It