Lincoln Park Zoo staff look for bat roosts, like the one pictured here, to collect samples of the bats' guano, or poop. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Lincoln Park Zoo staff look for bat roosts, like the one pictured here, to collect samples of the bats' guano, or poop. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Matt Mulligan will spend about three weeks this year driving to barns, picnic pavilions and other man-made structures on the outskirts of Chicago in search of bat poop – lots of it.

Since last year, Mulligan, a wildlife research coordinator at Lincoln Park Zoo, has been leading an effort to collect samples of bat guano in five counties surrounding Chicago: McHenry, Lake, DuPage, Will and Kane.

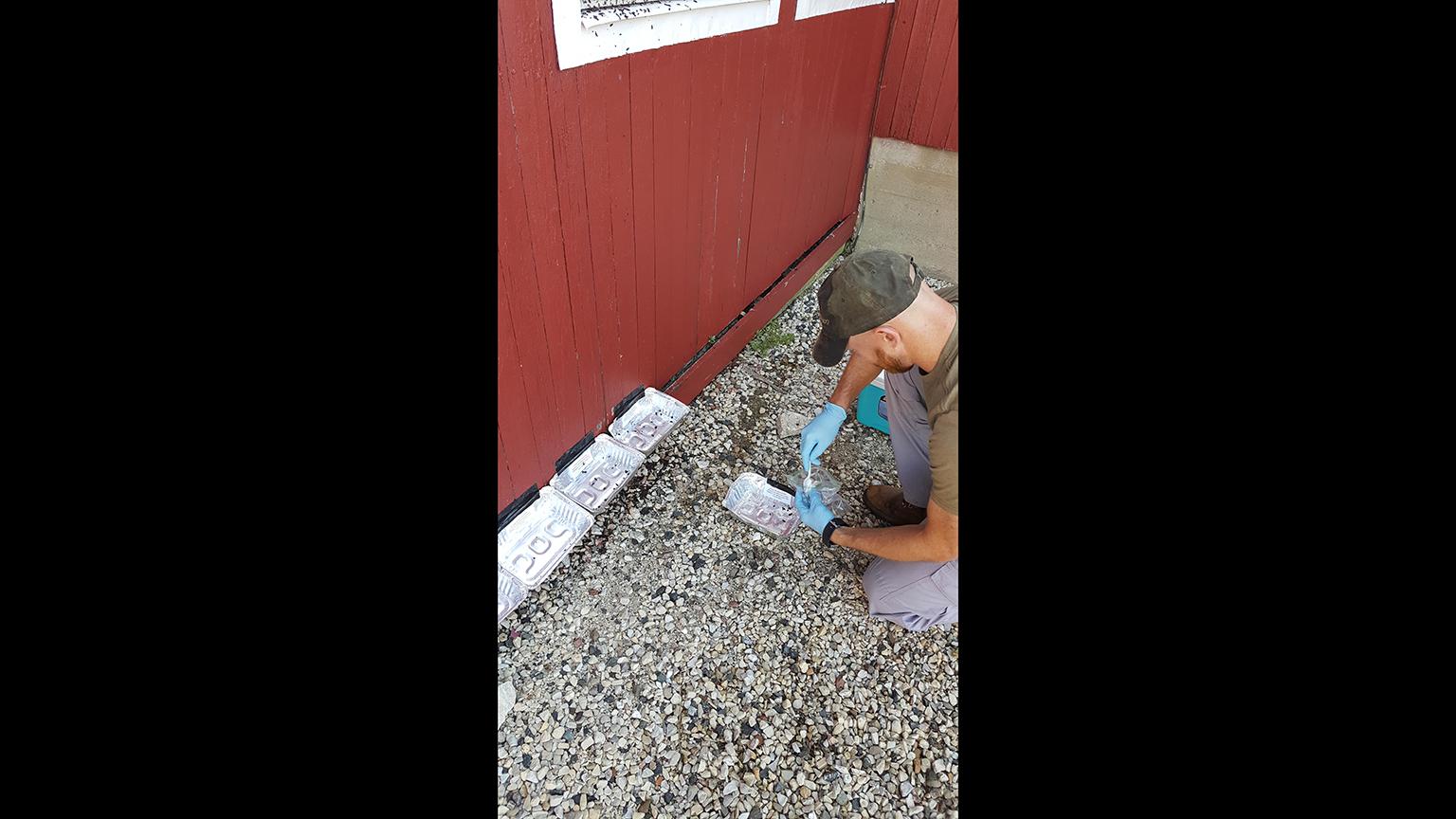

For one week each in April, July and September, Mulligan shuttles around to active bat roosts in the late afternoon, finds where the bats are defecating and places an aluminum pan (like the ones used for cooking turkeys) underneath. The next morning, Mulligan returns to retrieve what he hopes is an ample collection of guano pellets, which he scoops up with a plastic spoon and deposits into a plastic storage bag.

Between 2017 and this year’s collections thus far, Mulligan’s team has picked up somewhere from 2,400 to 4,800 pellets, mostly from little brown and big brown bats, which are most common in the area.

The samples are then analyzed by specialists at the zoo’s Davee Center for Endocrinology and Epidemiology to measure for levels of cortisol, an indicator of stress.

“We’re trying to understand the actual health of the bats,” Mulligan said. “We know the bats are at these specific areas; they’re coming year after year. How is their health related to the same species at another [location], and what are the factors that could be related to their health?”

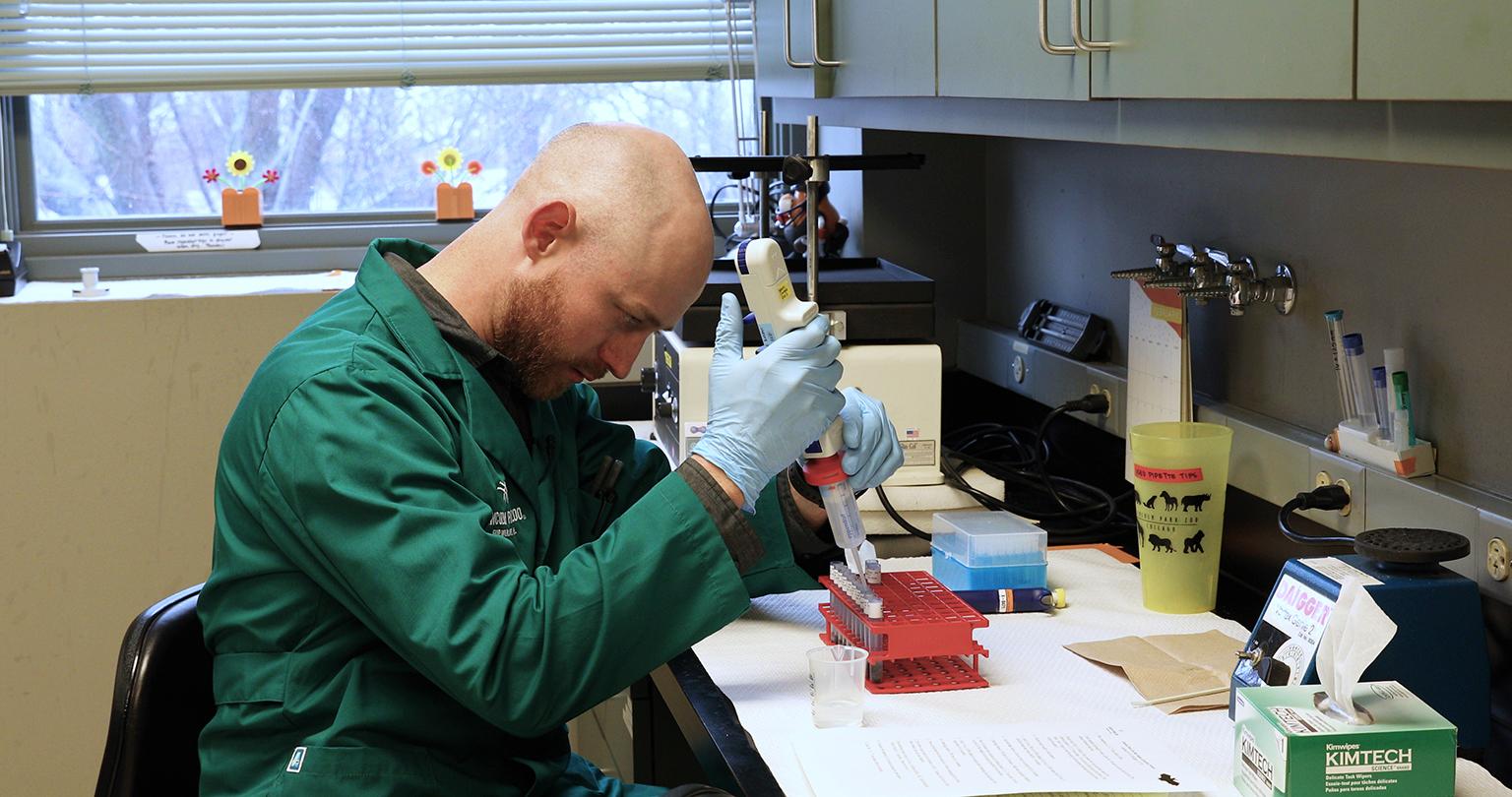

Matt Mulligan, a wildlife research coordinator at Lincoln Park Zoo, tests samples of bat guano to measure for levels of cortisol, an indicator of stress. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Matt Mulligan, a wildlife research coordinator at Lincoln Park Zoo, tests samples of bat guano to measure for levels of cortisol, an indicator of stress. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Finding bats is often a challenge because owners of homes or barns will usually “evict” ones that show up in the attic, Mulligan said. Bats also tend to roost in spaces that people don’t know about or do not use regularly.

To help track down bats, Mulligan’s team operates an email account, [email protected], where residents can report bat sightings. Some people have even sent photos and videos.

“It’s difficult sometimes to find [bats] that are left alone,” he said, adding that locating bats in Cook County has proven especially challenging given its density.

Although Mulligan said more data is needed to accurately assess the health of bats in the region, one key preliminary finding indicates that bats living in areas with more people tend to have higher stress levels than bats living in more remote locations.

Stress levels can affect bats’ ability to fight diseases like white-nose syndrome, a fungal infection that devastated bat populations across the country, including in Chicago, about five years ago.

The fungus causes bats to wake up more often during hibernation, sucking up their reserves, Mulligan said.

Mulligan’s guano project supplements a bat-monitoring program launched by the zoo in 2013 – at about the time when the white-nose syndrome started wiping out bats.

Lincoln Park Zoo's Matt Mulligan collects samples of bat guano in the field. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Lincoln Park Zoo's Matt Mulligan collects samples of bat guano in the field. (Courtesy Lincoln Park Zoo)

Run by Liza Lehrer of the zoo’s Urban Wildlife Institute, the program uses microphones placed in trees across the region to record bat calls. The recordings are then run through a software program that allows zoo staff to identify bat species that have returned to the area after hibernating for the winter.

Both efforts come at a crucial time for bat species in the region and across the globe. As of last year, the International Union for Conservation of Nature listed 77 species of endangered or critically endangered bats, including a handful in the U.S.

Bats play a key role in helping to control insect populations, serving as a natural option for mosquito abatement. Bats also contribute to the ecosystem by pollinating plants and dispersing seeds.

Ultimately, Mulligan hopes the guano project will provide a clearer picture of the factors that affect bats’ health, such as their exposure to noise and light. Such information would allow land managers to adapt spaces to better cater to bats, he said.

“Each study is like a puzzle piece to give the whole picture,” Mulligan said. “Especially with bats, they haven’t been studied a whole lot.”

Mulligan said the zoo will continue collecting bat guano samples next year and, depending on funding, hopefully for several additional years, which he said is needed to acquire more data.

“All we can really do [now] is kind of compare between our sites and between different individuals,” he said. “My idea is for [the study] to go as long as we need it to.”

Contact Alex Ruppenthal: @arupp | [email protected] | (773) 509-5623

Related stories:

New ‘Bat Condo’ is 6th to Be Installed in Cook County

Bat Houses in Cook County Missing Just One Thing: Bats

Acoustic Monitors Track Return of Bats in Chicago