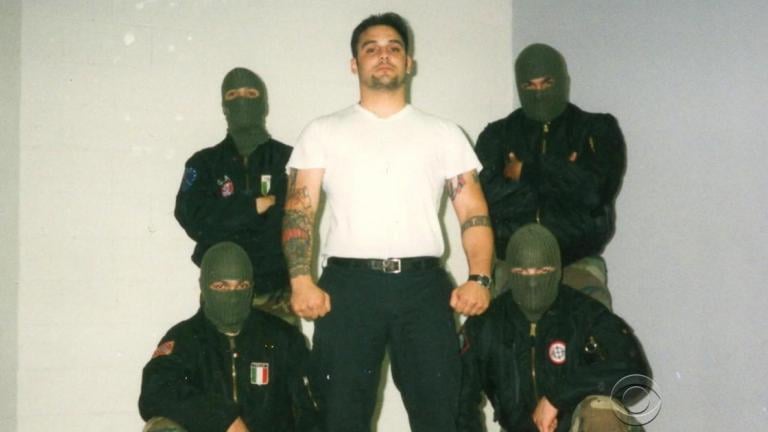

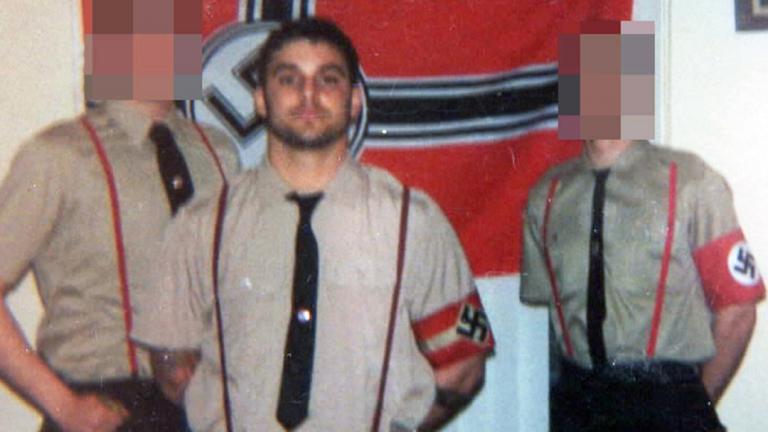

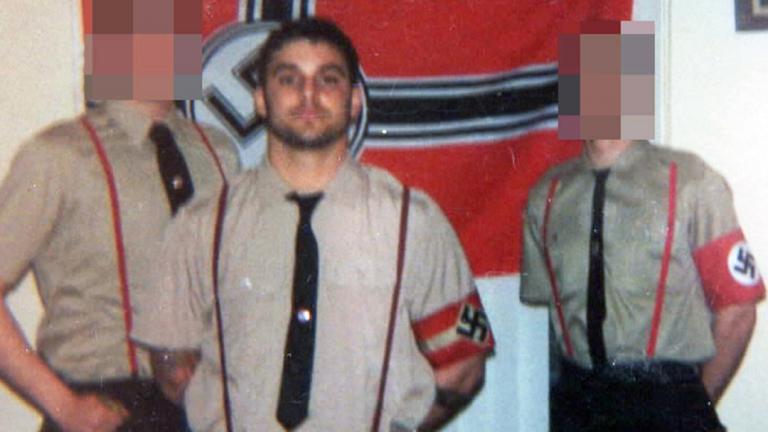

Growing up in Chicago during the 1980s, Christian Picciolini joined and later led the Chicago Area Skin Heads, or CASH – one of the first racist skinhead groups formed in the U.S.

As the lead singer of several white power rock bands, Picciolini toured the country and even internationally, using hate-filled music as a way to spread neo-Nazi propaganda and attract young recruits.

In 1996, after nearly a decade as a white supremacist, Picciolini fully renounced his past and pledged to deradicalize others entrenched in hateful ideologies.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day nine years ago, Picciolini co-founded Life After Hate, a nonprofit dedicated to educating and reforming individuals involved in extremist groups.

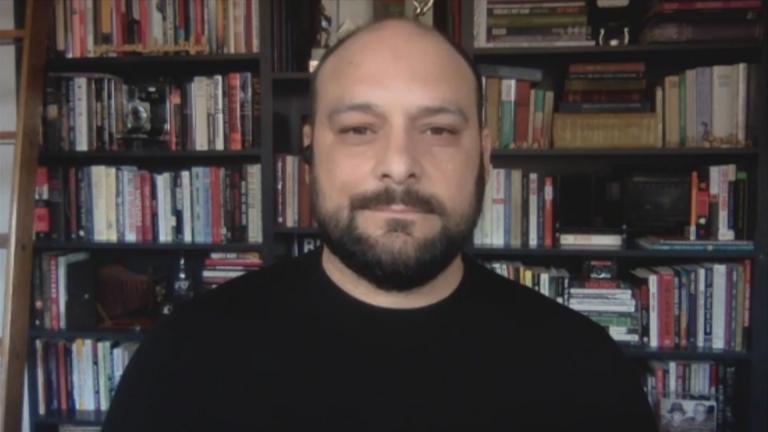

Picciolini is now telling his story in a new book, “White American Youth: My Descent into America's Most Violent Hate Movement--and How I Got Out.” He joins us to discuss his life within the white supremacist movement, his subsequent efforts to combat racism and today’s political climate.

Below, a Q&A with Picciolini.

Chicago Tonight: What was your mission in writing this book?

Christian Picciolini: I essentially wanted to have it reach other young people who might be struggling with an identity, community and purpose – not necessarily anyone who’s going down a white supremacist path, but I think the book is relatable to everybody – even parents trying to understand why young people join extremist movements. It’s certainly an insight into a movement that’s making a resurgence in America today.

How vigilant should Americans be in regard to white nationalism and domestic terrorism? Is it an underestimated threat?

I do believe it’s growing. I believe we’re using tactics in many ways that are emboldening them. Even though we’re trying to do the right thing by trying to dismantle white supremacy, I think in some ways, the way we attack them is pushing them further down the hole and creating some momentum for them, actually.

I think we’re facing a problem right now where our youth are joining this as a social movement, adopting the ideology and we’re losing them to it because of all the division that’s happening in the country.

It seems you came from a loving family. What prompted you to join a hate group? And as your book describes in vivid detail, how could you find the nerve to commit racially-charged violence?

You know, I can tell you it wasn’t ideology or dogma which pushed me in that direction. I felt like an abandoned youth who was very ambitious but never really felt supported. I was essentially marginalized – not only from family, but friends and schoolmates. Growing up I felt like I was on the fringes. The first person who offered me a lifeline was a person who I met in an alley at 14 years old. And that person happened to be America’s first neo-Nazi skinhead leader [Clark Martell]. He drew me in with the promise of paradise. He gave me an identity and community and directed my purpose.

Had somebody else walked in front of my path at that very vulnerable age, I certainly would’ve gone in another direction, but for me, it was appealing because it was the last option for me. I was also very angry and they were the angriest people I could find. I was able to relate to that. The racism came later.

As a skinhead, one American tenet you railed against was capitalism. Do you find it ironic that owning Chaos Records, your own record store – and interacting with diverse clientele – helped you distance yourself from your white supremacist roots?

It was music and capitalism that helped provide a platform for me to meet the people that I had kept outside of my social circle and hadn’t had any meaningful reactions with. I met African-Americans, gay people, Jewish people and others. I suppose it was the record store that started it, in order for me to support my family. It was interesting selling this other music that I was trying to make money from was essentially what connected me with the people I was so disconnected from.

Do you regret your past?

Of course. I feel shame about what I’ve done every day for the last 22 years and even counting the eight years that I was involved, I always had questions. But I can choose to let that shame keep me where I was and bog me down or I can use that information and momentum to move forward and help other people get out.

Do you think your message can hold resonance with people even outside far-right extremist circles?

Absolutely. I think my story is a cautionary tale for anyone who is lost. For anyone who’s confused about what might be happening in the world and what their contribution to the world might be. I’d say it’s relatable to anyone of any race and age, who’s either going through it or might know somebody who’s going through it.

Related stories:

Chicago Group Opposing Neo-Nazis Planned to Target Jihadists, Too

Chicago Group Opposing Neo-Nazis Planned to Target Jihadists, Too

Aug. 23: A group cited for its efforts to thwart white supremacists has plans to counter Islamist extremists. But after the Trump administration revoked a $400,000 grant to Life After Hate, those plans may be on hold.

Former Neo-Nazi on White Supremacy: ‘It’s Terrorism’

Former Neo-Nazi on White Supremacy: ‘It’s Terrorism’

Aug. 21: “Until the government starts to call it what it is – and that’s terrorism – I’m not sure the point will fully come across as to how dangerous of a problem this is,” said Christian Picciolini, a former neo-Nazi, of far-right extremism.

Life After Hate: Former Skinhead Leader Reflects on Personal Transformation

Life After Hate: Former Skinhead Leader Reflects on Personal Transformation

May 6, 2015: Christian Picciolini was once a neo-Nazi skinhead leader in Chicago. Today he runs an organization called Life After Hate. Jay Shefsky tells the story of Picciolini's remarkable transformation.