H.H. Holmes is considered America’s first serial killer. He built a hotel of horrors to lure and kill guests during the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893.

Holmes’ so-called “murder castle” featured a maze of secret hallways, false floors, trap doors and soundproof rooms outfitted with vents through which he’d send poison gas to asphyxiate his guests.

Holmes sent the bodies down chutes to a makeshift morgue in the basement where he’d dispose of his victims, later to sell their skeletons to medical schools.

The “White City devil” was put to death for killing only one man – but was he actually hanged? Rumors abound he cheated death and escaped to South America.

Holmes’ descendants just had his body exhumed to finally put the mystery to rest.

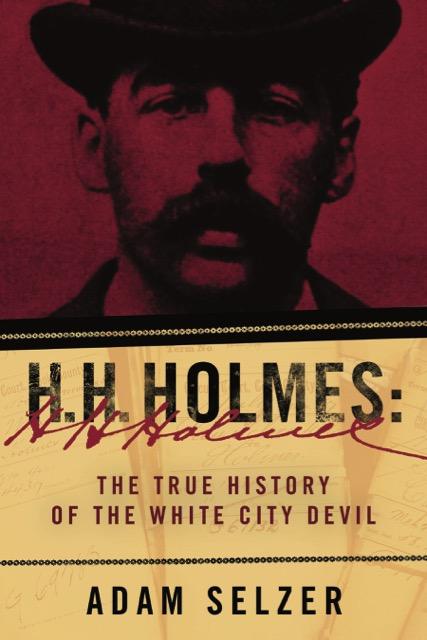

Joining host Phil Ponce to talk about the latest twist is Adam Selzer, author of the new book “H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil.”

Below, an excerpt from the book.

![]()

Introduction

In March of 1893, when Carter Harrison was running for a fifth term as mayor of Chicago, the Chicago Evening Post warned that if Harrison were in charge of the city during the upcoming World’s Fair, every criminal in the world would be moving right to town.

“It is the business of crime to know what places are safe,” they wrote. “When a town or city is labeled ‘right,’ murderers, thieves, safe-blowers, highwaymen, pickpockets, and all species of criminals inquire no further. It goes down on their list as a place where they will be insured protection in the prosecution of any nefarious calling in which they may be engaged. For a month every train that entered Chicago has brought recruits. . . . ‘On to Chicago’ is the cry of the criminal army, and on to Chicago that army is marching. Part of it is here already, and if Carter Harrison should be elected Mayor, the city will be given over to plunder.”1

“It is the business of crime to know what places are safe,” they wrote. “When a town or city is labeled ‘right,’ murderers, thieves, safe-blowers, highwaymen, pickpockets, and all species of criminals inquire no further. It goes down on their list as a place where they will be insured protection in the prosecution of any nefarious calling in which they may be engaged. For a month every train that entered Chicago has brought recruits. . . . ‘On to Chicago’ is the cry of the criminal army, and on to Chicago that army is marching. Part of it is here already, and if Carter Harrison should be elected Mayor, the city will be given over to plunder.”1

In one of those strange coincidences that can sometimes make history feel like quantum physics, Chicagoans reading the Tribune that morning had already been treated to the first major article about a South Side man who went by the name of H. H. Holmes.

Soon, he would be given titles such as “The Arch-Fiend of the Age” and “The Greatest Criminal of this Expiring Century”2 and would be described as “the most perfect incarnation of abysmal and abnormal wickedness to pass from history into the lurid vagueness of legend.”3 As of March of 1893, he was only thought of as an inventive swindler, but the elements of a story that could grow into a really ripping legend were all in place.

Buried among news about the World’s Fair (and the Tribune’s own condemnations of Harrison), the lengthy article said that Holmes was using hidden rooms and secret passages in his Englewood building to defraud his creditors:

HID IN SECRET ROOMS

Where Dealers Discover Their Missing Furniture

Mr. Holmes Purchases It, Takes It To His World’s Fair Hotel on Sixty- Third Street, and Neglects to Settle — A Search for the Property Leads to the Discovery of Apartments Between Floors and Ceilings In Which Some of the Goods Are Stowed.4

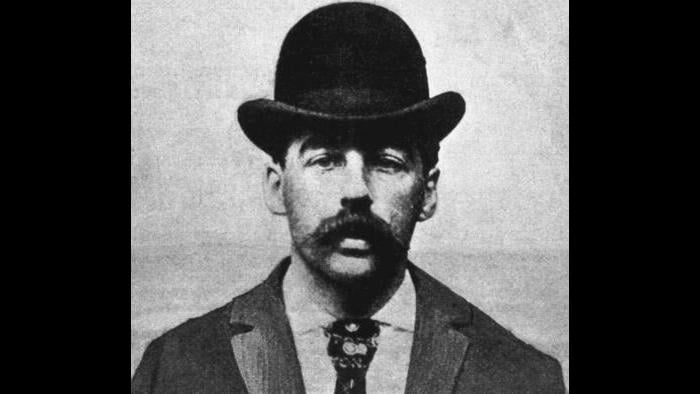

A little over thirty years old, Holmes had been in Chicago for six months, according to the Tribune (though it was really more than six years). A trained doctor and a pharmacist by trade, he would later be described as “a man of medium height, slight build, and a very nervous temperament. He has a habit of winding his fingers together while talking. He has a little black mustache and a pair of cold blue eyes, one of which, like his record, is not straight.”5 No one could possibly write a better description of a classic melodrama villain.

Soon, people would be calling his building “The Holmes Castle” and, decades later, “The Murder Castle.” Though later investigations there failed to turn up much that was particularly damning, an untrained and unqualified new police chief convinced himself—and the newspapers—that he’d discovered a building that would clear up every unsolved crime of the Harrison era. Newspapers went along for the ride, and eventually Holmes, by then awaiting execution for one single murder, did, too.

By the twenty-first century, Holmes had entered American folklore as the man who built a hotel full of torture chambers to prey on visitors who came to the World’s Fair and may have killed hundreds of people, making him our first and most prolific serial killer. Holmes had already been known as the “king of criminals” before he’d even been formally accused of murder, but now he was a veritable supervillain.

If you trace the story about Holmes day by day, then through the years, you can see how many of the most common tales about him simply grew out of idle gossip in newspapers and police propagating theories that would be promptly dismissed as nonsense. But no one did more to turn the gossip into legend than Holmes him- self. The man was, beyond doubt, a pathological liar. He lied to his various wives, to his friends, to his lawyers, to his employees, to detectives, to reporters, and to everyone else, right down to the census man. He lied in his diary.

Many of the stories of him and his “Castle” are pure fiction. The castle never for one day truly functioned as a hotel, and the actual number of World’s Fair tourists he’s suspected of killing there has remained the same since 1895—a single woman, Nannie Williams. The hidden rooms were almost certainly used more for hiding stolen furniture than for destroying bodies. The legend of The Devil in the White City is effectively a new American tall tale—and, like all the best tall tales, it sprang from a kernel of truth.

Holmes’s career and the 1895 investigation into his “castle” is one of the most fascinating chapters in the annals of Victorian crime. There was a diverse cast of characters assembled around Englewood in July and August of 1895. Apart from Holmes’s wife and employees, there were reporters, lawyers, amateur detectives, families of the missing, former castle residents, incompetent police chiefs, shady lawyers, and throngs of the curious. It was a real-life mystery, and everyone tried their hand at figuring out what Holmes had been up to in that building, and what had become of the people who had disappeared from the place.

In Philadelphia, where Holmes was awaiting trial, there were daring sleuths, vengeful insurance companies, a fiery district attorney, a rising legal star, mad scientists, and conniving reporters. There was even a bumbling attorney who successfully became Holmes’s lawyer by means of a cheap stunt—and found himself in way over his head.

Elsewhere around the country, there were more swindling victims, former cellmates, relatives of the missing, old classmates, and family members who all had something to say about the man.

And at the center of it all sat H. H. Holmes, a frail little man in a prison cell spinning yarns for the press and sending investigators on wild-goose chases.

His story took place during a wonderful transitional period of history, when society floated between the old world and the new. The generation who fought the Civil War was slowly drifting out of public life; Holmes was of the generation right after, the Theodore Roosevelt generation that would lead America into the twentieth century. In 1886, when he arrived in suburban Englewood, Illinois, the gaslights were five years old, and electricity was just a few years away. Photographs were common, though the means of reproducing them were not—newspapers published drawings of photos instead of the actual shots. Moving pictures had been invented and would debut publicly while Holmes was in town, but they weren’t yet being used to document news—the first movies shot in Chicago wouldn’t be filmed until the year Holmes died. Sound could now be recorded and reproduced, but phonographs were still far beyond the means of most buyers. A number of businesses now listed a four-digit telephone number in their newspaper ads, but few citizens had phones with which to call them. Trains ran in and out of Englewood constantly, streetcars started operating in the neighborhood while Holmes was there, and he might have even seen an automobile go by on Sixty-Third Street every now and then, but horses were still essential to everyday transportation.

The sort of forensic analysis of human remains that could have convicted him in Chicago was only a couple of years off. Bones were found in Holmes’s cellar, but the current science couldn’t determine whose bones they were, or if they were even human. Yet by the end of the decade, scientists would have been able figure it out. Holmes’s career and crimes came in the last era of human history when they’d have to remain a mystery, subject to wild speculation and helpless against what the Philadelphia Press called “the lurid vagueness of legend.”

I began researching Holmes when a tour company I worked for asked me to start running tours of sites associated with him. Almost none of the buildings he can be traced to are still standing, and my first tours were simply based on the books about Holmes that were available at the time, most of which told the same basic story of a man who was “born with the devil in (him),” who’d built a castle to kill World’s Fair patrons and sell their skeletons to medical schools, and may have repeated the trick hundreds of times.

To give myself more to talk about between stops, I began poring through microfilm archives of Chicago newspapers, reading the firsthand accounts of investigations into the “Murder Castle” (a term that wouldn’t become common until decades after Holmes died). Right away, I discovered that a major part of the story I thought I knew was wrong: every article I’d read said that the castle burned to the ground in 1895. In truth, there was a fire there that year, but the building was still standing (with the top two floors rebuilt) for more than forty years before it was finally razed, and papers spoke of it frequently in the early twentieth century. An uncropped version of the most common photograph of it even showed a 1930s pickup truck near it.

Separating fact from fiction turned out to be a tremendous task—it soon became apparent that Holmes’s real story was very different from the story that had been told throughout the twentieth century. Nearly all of the Holmes legend as we know it can be traced to two or three tabloid and pulp articles, and thousands of firsthand accounts, articles, witness statements, and legal documents had been sitting unexamined, buried in microfilm reels and boxes of crumbling paperwork.

Sometimes it feels like a treasure hunt. I’ve spent many enjoyable afternoons at the court archives in Chicago, combing through the microfilms indexes and trying to find lawsuits that involved Holmes. It’s tricky, due to his tendency to use aliases; he would often list names of other people as the titular owners of his property, so the data about him could be hidden in lawsuits in the names of peripheral characters in his life.

The Internet, of course, gave me an advantage over many previous Holmes researchers. I had access to full-text searches of books that would have been very hard to find in libraries, including some incredibly rare volumes that turned out to be full of solid primary data. Even after years of searching, it was only after I’d finished the first draft that I stumbled onto what may be the biggest find of Holmes data ever: criminologist Arthur MacDonald’s report on Holmes, which included more than thirty letters about Holmes from former associates, including several classmates, professors, and his first wife. Published using initials in place of proper names, and therefore hard to find, none of the letters have ever been cited before. These materials provided tremendous insight into Holmes’s background and character.

Much of the best information about Holmes was published in period news- papers, and those have formed the most important sources for everyone who’s written about Holmes, including me. But not every newspaper article is reliable; indeed, no paper is a completely good source for Holmes. The story takes place in several different cities, and no paper had a reporter working in all of them. Hence, some Chicago papers were magnificent sources of info on the “castle” investigation, but terrible in their reports about the trial in Philadelphia. Papers in Philadelphia and New York spoke to Holmes in his cell and covered the trial better than the official transcript, but their reports on the castle are all second- or thirdhand. Boston papers sent reporters to interview his family and old neighbors around New England but provided little info of use on Holmes’s current situation.

I believe that it’s important to stick primarily with papers that had a reporter on the ground for the story they were reporting—Chicago papers for things that happened in Chicago, Philadelphia papers for things that happened there, etc. Out-of-town papers would often cover it when a story went around that a skeleton articulator said he’d purchased bodies from Holmes, but most didn’t bother to announce that Chicago reporters had found that the man’s story didn’t hold up. In any case, I have tried to include any data that I felt was of real value, as well as less reliable data that became an important part of the legend. Anytime I quote a source that I feel is questionable, I’ve flagged it.

The rise of digitization has made this research far easier, but being in Chicago was still essential to my research. Many of the best Chicago newspapers from the Holmes era have never been digitized and can only be accessed on microfilm. I couldn’t have found the boxes and boxes of crumbling old legal papers elsewhere, either.

I was able to access some rare and important materials in St. Louis and Washington, D.C., as well, but time and budget didn’t permit me to dig everywhere I would have liked. Probate and lawsuit records in Texas probably have some excellent information about a few of Holmes’s victims, and on his dealings in Fort Worth. Microfilmed papers in other cities are probably full of treasures, as well. There may even still be some “grewsome clews” (as newspapers of the day spelled those words) out there someplace.

For instance, what happened to the trunk full of bones and other relics that the Chicago police put into storage?

What about the evidence that the Philadelphia district attorney gathered? Or the stack of letters and artifacts that an amateur detective collected?

Or the letter Holmes wrote to the police chief in Chicago on the eve of his execution?

Or the other 170+ letters Dr. MacDonald claimed to have collected?

Or the photographs of Holmes and his victims that are once known to have existed but now survive only in the form of drawings of them made by newspapers?

Or the manuscript of his autobiography, which may have been wildly different from the printed version?

There’s a lot of mystery left to be solved here, and finishing this book doesn’t mark the end of my search. I’ll post any updates on my blog at MysteriousChicago.com.

See you at the library!

Adam Selzer

Fall, 2016

Excerpt from “H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil” reprinted with permission.

Related stories:

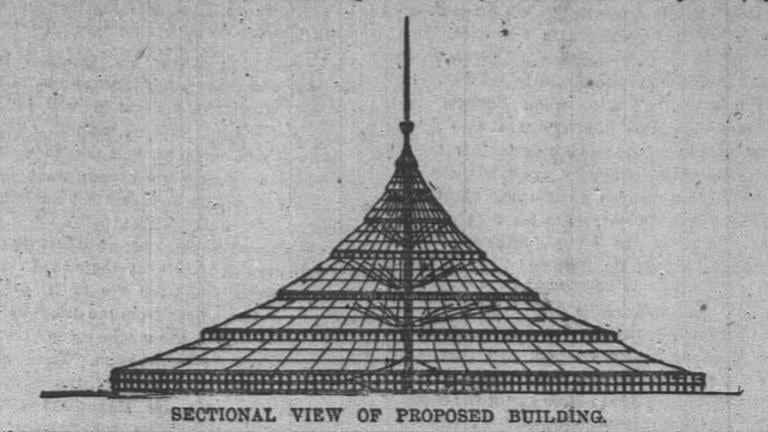

Ask Geoffrey: A ‘Pipe Dream’ of the 1893 World’s Fair

Ask Geoffrey: A ‘Pipe Dream’ of the 1893 World’s Fair

May 10: Geoffrey Baer explores an eccentric architect’s wacky proposal for the World’s Fair.

Author’s ‘Immortal’ Story Comes to Life on HBO

Author’s ‘Immortal’ Story Comes to Life on HBO

April 24: A new film on HBO starring Oprah Winfrey tells the remarkable story of Henrietta Lacks. We revisit our conversation with the Chicago author who tells the story.

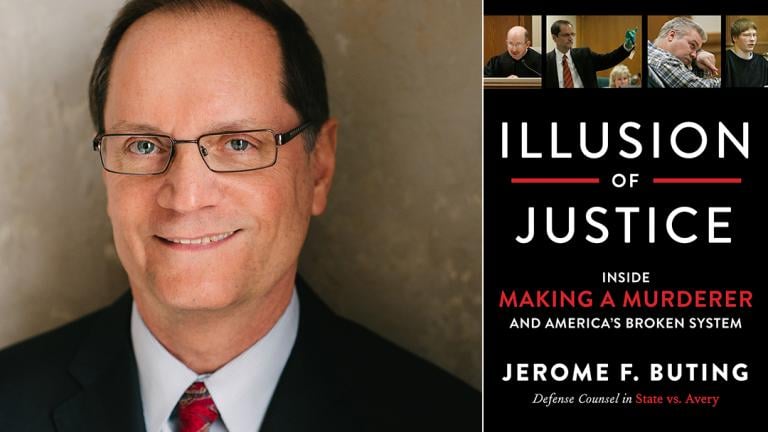

‘Making a Murderer’ Defense Attorney on Broken Justice System

‘Making a Murderer’ Defense Attorney on Broken Justice System

March 20: One of Steven Avery’s defense attorneys from Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” discusses his new book “Illusion of Justice.”