S.H. Bell's bulk storage facility along the Calumet River on Chicago’s Far Southeast Side. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

S.H. Bell's bulk storage facility along the Calumet River on Chicago’s Far Southeast Side. (Alex Ruppenthal / Chicago Tonight)

Editor’s note: This story was updated Feb. 9 after speaking with a representative of S.H. Bell.

They thought it was over when the black dust went away.

For decades, residents on Chicago’s Far Southeast Side complained about thick clouds of black dust blowing across their neighborhoods, through their windows and even into their mouths.

The dust came from uncovered piles of coal and petroleum coke, or petcoke, a solid byproduct of the oil refining process that is stored at sites in this heavily industrial corridor along the Calumet River, just south of the Chicago Skyway bridge.

Part 2 of our series: ‘Public Health Hazard’ in Ohio Has Chicago Community Concerned

Part 2 of our series: ‘Public Health Hazard’ in Ohio Has Chicago Community Concerned

Ever present, the black dust coated the bottoms of the feet of children playing outside and sprinkled itself on potato salads at neighborhood picnics.

But about four years ago, residents in the East Side and South Deering neighborhoods started to complain, a lot. And they organized.

Led by groups like the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke and Southeast Environmental Task Force, community members complained enough about the black dust to set off a chain of events that included investigations by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Illinois EPA, a lawsuit by Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan and new city regulations requiring bulk storage facilities to minimize dust emissions.

Today, the black dust is, for the most part, gone.

“We’ve just been used to having this dust here for so long,” said Annamarie Garza, a longtime East Side resident with four children. “I thought we were done.”

About three weeks ago, Garza and 25 other parents from Matthew Gallistel Language Academy showed up for a PTA meeting at the school. Waiting for them was Olga Bautista, an organizer with SETF.

Bautista had bad news: Air pollution monitors installed at one of the nearby bulk storage sites during the petcoke battle had detected potentially dangerous levels of manganese, a metal used to produce steel and found in other minerals in combination with iron. The data were collected by the EPA in 2014-15 from monitors set up at KCBX Terminals.

Olga Bautista of the Southeast Environmental Task Force. (Terry Evans / Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Photography)

Olga Bautista of the Southeast Environmental Task Force. (Terry Evans / Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Photography)

Although manganese is a nutrient essential for neurological function, at high concentrations, it can cause neurological deficits and affect motor functions, according to the EPA. The agency says exposure to elevated concentrations of manganese in the air can lead to a permanent neurological disorder known as manganism, the symptoms of which include tremors, difficulty walking, facial muscle spasms and mood changes.

The risk is even greater for children, unborn babies and nursing infants. Exposure to high concentrations of manganese can affect brain development, including changes in behavior and decreases in learning and memory capacities, according to the EPA.

“When we found out about manganese, I called them right away,” said Bautista, who is friends with mothers of Gallistel students. “They were upset. They were really upset.”

Much remains unknown. It is unclear, for example, how much manganese is in the air. One facility in close proximity to the monitors that detected the manganese, S.H. Bell Co., has for nearly three years avoided installing monitors.

According to a complaint filed by the EPA against the company in August, “S.H. Bell has refused to install air pollution monitors at its bulk material handling facility in southeast Chicago, Illinois.”

The monitors are required by a notice of violation from the EPA under the Clean Air Act.

In December, the EPA and Department of Justice announced a settlement with S.H. Bell mandating that the company install air monitors, in addition to paying a $100,000 civil penalty.

In response to questions from Chicago Tonight, S.H. Bell said in a statement dated Jan. 30: “The settlement calls for the monitors to be installed no later than March 1, 2017, and S.H. Bell is committed to meeting that deadline.”

However, on Feb. 1, Chicago's Department of Public Health notified the company that it had denied its request for an extension. The EPA, which set the March 1 deadline, stated in its settlement with S.H. Bell that it would defer to the city on the matter. In a letter sent to S.H. Bell, CDPH said the company must install and activate the monitors within two weeks from the date of the letter, which puts the new deadline at Feb. 15.

The letter states if the company fails to comply, it will be subject to enforcement action, "including daily fines in the amount of $1,000 to $5,000 per violation."

Garza said many residents and parents do not yet know about the manganese exposure, an issue that came to light last summer in a report published by the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

That’s changing, though. On Tuesday night, the Southeast Side Coalition to Ban Petcoke held a meeting to alert community members about the manganese.

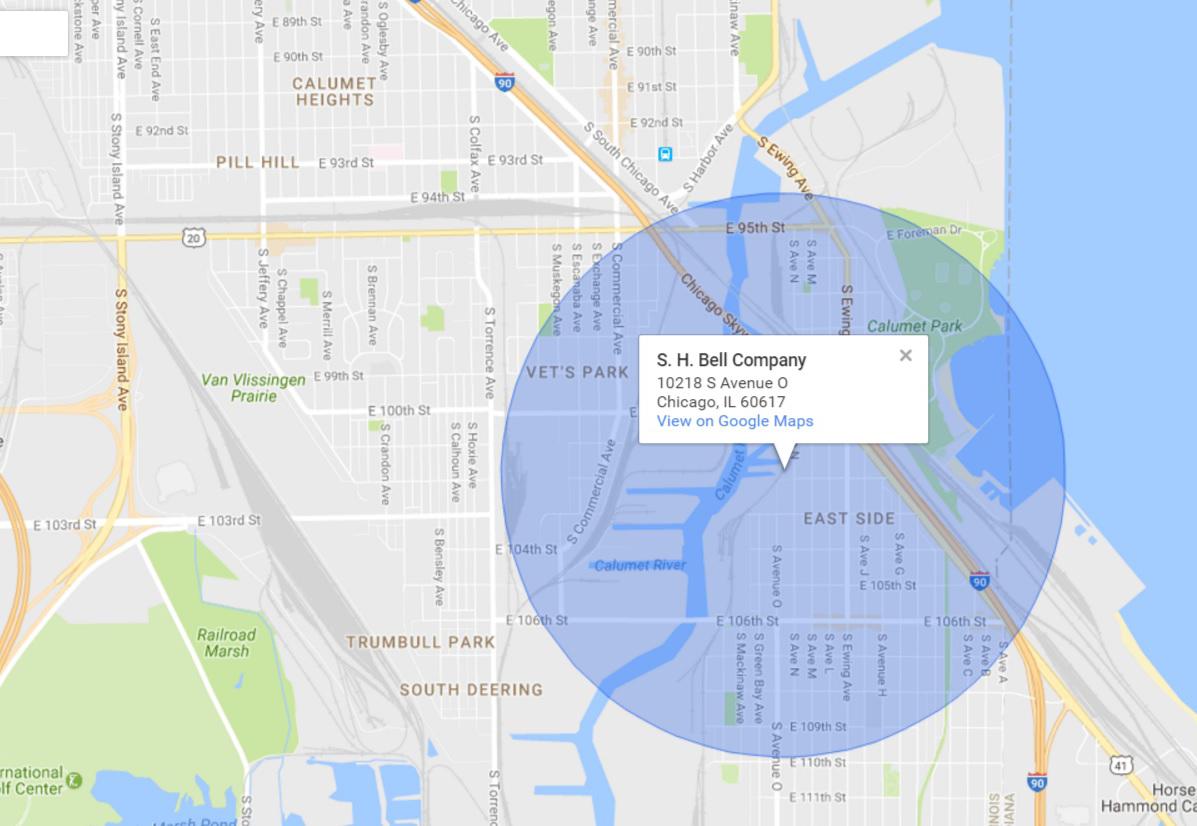

According to SETF, about 20,000 residents live within 1 mile of S.H. Bell, which the ATSDR identified as the likely source of manganese in its report released last summer.

“People are just starting to get informed,” Garza said.

About 20,000 residents live within one mile of S.H. Bell's Chicago facility, according to the Southeast Environmental Task Force.

About 20,000 residents live within one mile of S.H. Bell's Chicago facility, according to the Southeast Environmental Task Force.

Unlike with petcoke, which left black stains on roofs and coated the outside of cars, manganese dust is more difficult to detect. Some residents have reported a yellow coating on their houses that matches the fingerprint of manganese, said Meleah Geertsma, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“[But] I don’t know that there’s anything super distinguishing about it,” said Geertsma, one of three attorneys who co-authored a letter urging Chicago’s Department of Public Health to require that S.H. Bell stop handling manganese at its facility.

The letter, sent to the city Jan. 11, was also signed by attorney Keith Harley on behalf of Bautista’s group, the Southeast Environmental Task Force.

“I don’t think the community has realized to date what they’re sitting on,” Bautista said.

Follow Alex Ruppenthal on Twitter: @arupp

![]()

In Part 2 of our series, an environmenthal health professor shares results from the first study in the U.S. to examine the effects of manganese exposure in children – and how the chemical might affect children on Chicago’s Southeast Side.

Video: Reporter Alex Ruppenthal discusses the story with Phil Ponce. Note: Some industrial images in the video show S.H. Bell operations; others show facilities near S.H. Bell.

Related stories:

Photography Exhibition Looks at Effects of Petroleum Coke in Chicago

Photography Exhibition Looks at Effects of Petroleum Coke in Chicago

July 26: For years, petroleum coke – the black, powdery byproduct of tar sands oil refineries – plagued Southeast Side neighborhoods along the Calumet River.

KCBX Denies Petcoke Dust Problem Despite Air Quality Violations

KCBX Denies Petcoke Dust Problem Despite Air Quality Violations

Nov. 25, 2014: The company that stores most of the petcoke on the city's southeast side is trying to get the city to relax its regulations.

Chicago Petcoke Ordinance Passes

Chicago Petcoke Ordinance Passes

April 30, 2014: The Chicago City Council passed an ordinance regulating petcoke today. Petcoke is a coal like substance, a byproduct of refining oil.